Sphere light

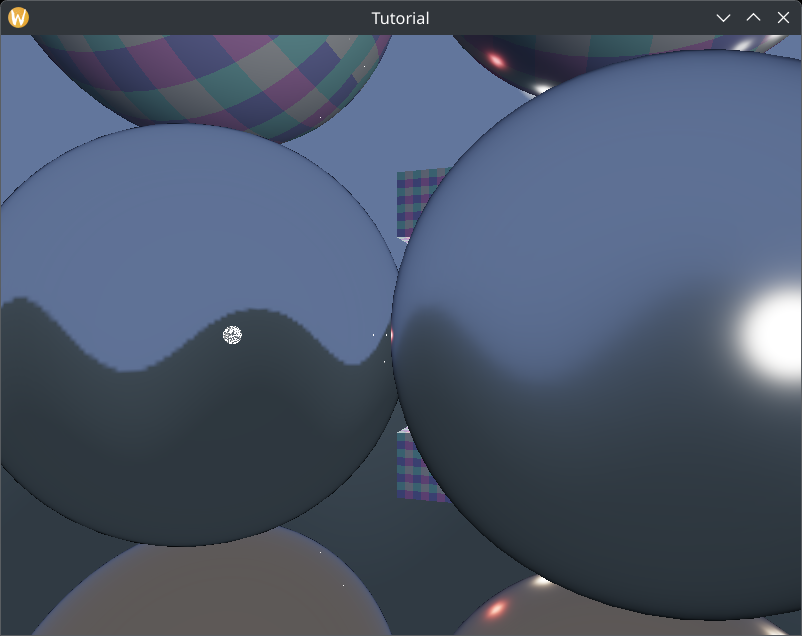

In the previous chapter we finally added a global illumination technique called environment mapping to our application. This was the last puzzle piece that made sure our physically based renderer does not look horrible, but there is still room for improvement. One of those is the not too pretty specular highlight on non rough materials.

The hack that may come to your mind is, "let's just make every material rough, that will make the specular highlight bigger", but one of the advantages of physically based rendering is an "author once run in every lighting condition" type of material editing. If you give golden color to a material it will behave like gold in every lighting condition. Similarly if you make a material glossy it will be glossy in every lighting condition. This should save work hours spent on material editing. If the system requires tweaking the material for certain lighting conditions, this benefit is lost.

The real problem is the zero area of the point lights. Sometimes we have a larger light bulb or a sun, and the error of assuming zero area really shows. If a light source is not a point light but an area light, then glossy materials just produce a larger highlight. In this tutorial we will implement a simple type of area light, a sphere light.

This tutorial is math and physics heavy and assumes you already have some intuition for calculus. The recommendations from the previous tutorials for consuming math still apply: you can understand math in many ways, depending on your way of thinking and background:

- Read and understand the math first, then the code

- Understand the code first, and then interpret the math

Read whichever way is better for you. Be prepared that multiple rereads may be necessary.

This tutorial is in open beta. There may be bugs in the code and misinformation and inaccuracies in the text. If you find any, feel free to open a ticket on the repo of the code samples.

Area light

In our diffuse lighting tutorial we had the rendering equation where an integral simplified into a simple sum thanks to the point light assumption. If we add area to our light source, the integral comes back.

First let's remember how a single light source contributes to our shaded surface, then we compare it to a single area light, and when we figure out the formula for a single area light, we can substitute it into a sum for every area light.

Let's remember how a single point light contributes to the reflected radiance! (Contrary to previous chapters, here we represent the light distance with instead of , because in this chapter we will start working with sphere radii and with the new naming scheme I want to avoid confusion.)

Following the "Area lights" chapter of the Frostbite doc The formula for a single area light with non uniform luminance distribution looks like this:

(Let's remember that the formulae for radiance and luminance generally take the same shape, just with different dimensions!)

The function is a visibility function that evaluates to 1 if the light's surface is visible, and 0 if it is not. It masks out occluded surface elements of the light source.

Now let's rewrite the previous integral as an integral over the surface of the light source! We need to calculate the solid angle from the infinitesimal surface element of the light source with area and normal . Let's remember that for any shape on the sphere with radius and area the formula for calculating the solid angle is the following:

A useful and intuitive special case is a cone cutting out the area from the sphere with radius .

Let be the direction vector pointing from the lit surface to the surface element of the light source and be its distance. We can use the projected area as the in the solid angle formula and as and this way we get the solid angle of the surface element subtended at the point of the lit surface element.

Using this information for transforming the integral results in the following equation:

Now we can start to specialize this further. We can do the following with this integral:

- solve the integral analytically if it is simple enough for specific surfaces and BRDFs

- hack together a formula that approximates the integral

We will go with the first approach for the diffuse lighting and the second one for the specular.

Sphere light

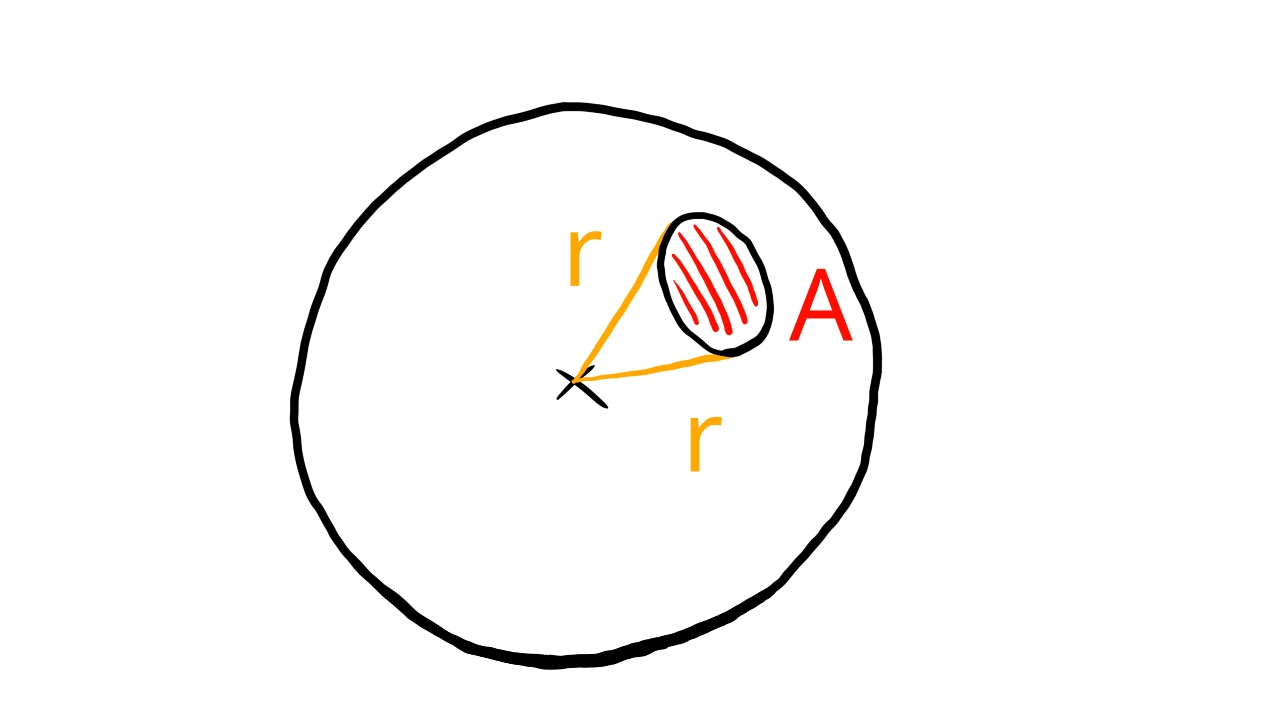

A sphere light is a light source that emits uniform light from a spherical surface with radius .

As we progress in figuring out formulae for lighting calculations we make the following two assumptions:

- Sphere lights emit light across a spherical surface

- Sphere lights emit uniform light across the whole surface

Diffuse lighting with sphere lights

The solution for determining the incoming radiance at a surface element from a sphere light can be found in the Frostbite doc.

Let's start out with plugging a constant radiance value (it depends on the wavelength but not the position of the surface element) and the Lambertian BRDF into the equation. We get this:

We could bring and out of the integral because they do not depend on the light surface element position. The only integral we have has a form that is similar to a quantity called the view factor. (The Frostbite document calls it Form Factor)

Among the Forstbite doc's references we find a document that contains the form factor of many shapes, including sphere. Now we can confidently rewrite our diffuse lighting equation to contain the view factor.

Pay attention! There is a in the denominator of the view factor, so we multiply with it outside the view factor.

Actually within the equation above a partial result (without the multiplication with the diffuse BRDF) is called the irradiance. I mention this just to make sure that a few variable names in the shader make sense. You will encounter this as you read the Frostbite doc.

Now we need to plug in a formula for the form factor of a sphere light, which based on the Frostbite doc and the view factor doc is below.

Where is the direction vector pointing from the surface element to the center of the sphere light, is the distance between the center of the sphere light and the surface element, and is the radius of the sphere light.

Now we have everything to write a shader that calculated the diffuse lighting coming from a sphere light. It's time for the specular lighting!

Specular lighting with sphere lights

Now it's time to find a method for handling specular lighting for sphere lights. The Unreal doc presents the representative point method.

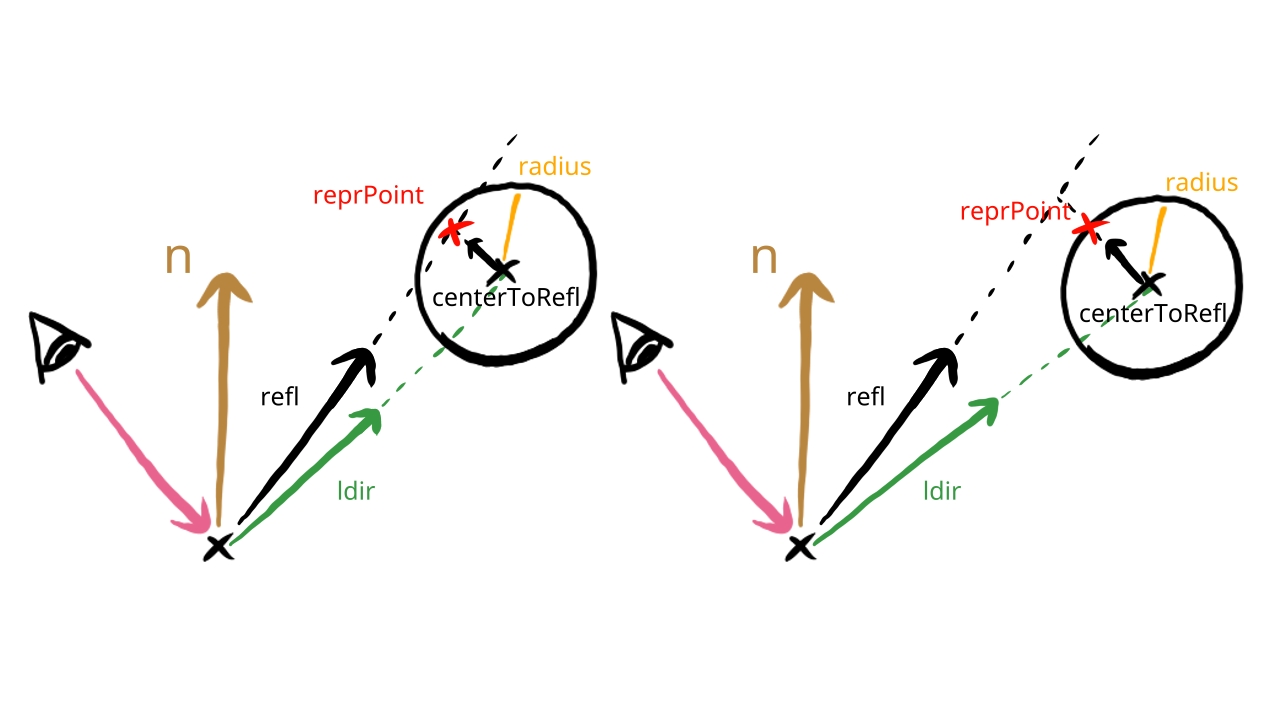

We model the radiance coming from the sphere light as the radiance coming from a point light in a representative point. We choose the point within the sphere light that is the closest to the mirror direction. Let be the mirror direction vector and be the vector pointing from the surface to the center of the sphere light. The representative point is given by the formula below.

We use basic vector algebra to find a vector pointing from the center of the sphere light to the line of reflection, which will be . We took the dot product between and , which gives us the length of the component of parallel to , multiply with it, getting the point along the mirror direction that is closest to the sphere center, and then subtract from it, getting the direction from the sphere center to the mirror direction's line.

Then we move from the center of the sphere towards the line of the mirror direction. If the distance of the line of the mirror direction is greater than the radius, we clamp it to the radius so it stays on the boundary of the sphere. This way the representative point will never go outside the sphere light.

We plug the direction pointing to this representative point into the point light equation, and we get a proper, non miniature specular highlight.

The only problem that we have is the energy conservation. By using this representative point method we essentially split our NDF in two and insert a constant function in-between. If the previous BRDF was normalized, we break this by adding the area under the inserted constant function, which breaks energy conservation. This is elaborated on in the Unreal doc. As long as we follow the rules of physically based rendering, a material authored once should work in any lighting condition. If we break energy conservation, we lose this advantage.

The solution given by the Unreal doc. is to multiply the NDF function with a normalization factor that approximately compensate for this.

The way we get this normalization factor is by looking at how the Trowbridge-Reitz NDF gets normalized when the roughness is larger and the distribution is wider, and see what factor normalizes the wider function. the Unreal doc claims that the Trowbridge-Reitz NDF gets multiplied by the factor, and to develop an intuition on where this is coming from, let's take a deep dive on how this Trowbridge-Reitz NDF really works.

First let's remember how the Trowbridge-Reitz NDF looks like!

We can rearrange this to have a normalization factor.

This distribution does not seem to have any readable intuitive meaning in any of these forms, but there is one! We just need to take a look at a different version of the Trowbridge-Reitz NDF.

That will be the anisotropic version. Let's take a look at the appendix B "GTR Microfacet Distribution" of the Disney doc to find things and it may help us build up the intuition for it. There is an anisotropic version of the D function that is very descriptive: if you read the formula you get a much better understanding of the driving principles behind how it works, and it will help with understanding the meaning of this normalization factor.

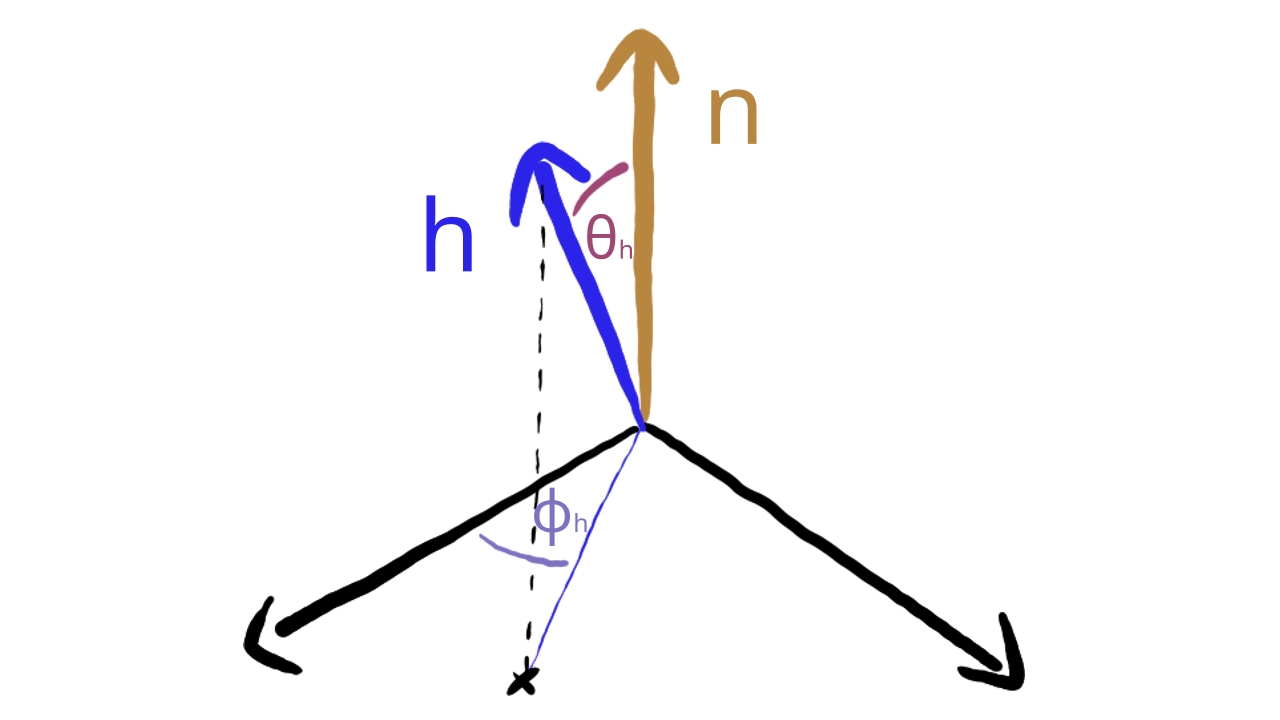

We have some new variables, and . What are they? is the angle between the half vector and the normal vector. To interpret let's understand what an anisotropic NDF is. Basically the roughness is direction dependent. There will be a direction within the plane perpendicular to the normal, let's name it x, along which the roughness is , and there will be another direction that is perpendicular to it, let's call it y, along which it will be . will be the angle between the x direction and the component of the half vector perpendicluar to the normal.

This anisotropic formula gives a very clear description on how the Trowbridge-Reitz NDF works: we construct a h vector that gets widened along two axis by the roughness parameters. The formula clearly says that the distribution gets widened by the absolute value of this h vector, which is lengthened perpendicular to the normal using the roughness parameter. These are the fundamental mechanisms of the D function, and now we should have a better grasp of the meaning of the normalization factor.

If we make it isotropic again, it gets even more clear. For that, must be plugged in.

We used the fact that . Now the meaning is even more clear: the component perpendicular to the normal gets lengthened using the roughness parameter. This time it is a uniform scaling within the plane perpendicular to the normal.

All we have to do now is reorganize it so we get back our original form of the Trowbridge-Reitz NDF to prove ourselves right.

This tought us a lot about the anatomy of the Trowbridge-Reitz NDF, and now we better understand the normalization factor that we need to adjust.

The actual way of replacing with in the normalization factor can be done by just multiplying the D function with .

Now we just need a new that would be the roughness of a wider distribution, and the Unreal doc recommends a formula:

With this our strategy for specular lighting with sphere lights is complete. The steps are the following:

- For every lit surface element, calculate the representative point.

- Calculate the incoming radiance from the representative point using the point light formula.

- Calculate the new roughness parameter.

- Normalize the D function using this new alpha parameter

We can finally get to coding.

Implementation

Now that we have the formulae for diffuse and specular lighting for sphere lights, we can get to implementing them. We need to perform the following tasks:

- We need to update our scene representation to store a new variable, the radius, for every light source.

- We need to update the upload code to upload this new variable to the GPU.

- We need to implement diffuse and specular lighting for sphere lights in the shader.

In this tutorial for the sake of simplicity we will replace point lights with area lights, but in a real world application both types of lights have their place, so in your own graphics engine you should support both types.

Uniform buffer layout

The uniform buffer layout does not need to change, because we have enough space and variables to store a new float. The position is already a 4 component vector. We can utilize its last parameter to store the radius.

CPU side scene representation

Here we add a new field to the struct Light, the radius.

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

struct Light

{

x: f32,

y: f32,

z: f32,

radius: f32,

intensity_r: f32,

intensity_g: f32,

intensity_b: f32

}

Let's fill this parameter for every light source! Let the first light be bigger than the rest, just to see the difference.

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

let point_light_radius = 0.0125;

let mut lights = Vec::with_capacity(max_light_count);

lights.push(

Light {

x: 0.0,

y: 0.0,

z: 0.0,

radius: 0.075,

intensity_r: 0.5,

intensity_g: 0.5,

intensity_b: 0.5

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: 0.25,

y: -0.25,

z: -1.9,

radius: point_light_radius,

intensity_r: 0.025,

intensity_g: 0.025,

intensity_b: 0.025

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: -0.25,

y: 0.25,

z: -2.9,

radius: point_light_radius,

intensity_r: 0.025,

intensity_g: 0.025,

intensity_b: 0.025

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: 1.5,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.5,

radius: point_light_radius,

intensity_r: 0.125,

intensity_g: 0.125,

intensity_b: 0.025

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: -1.5,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.5,

radius: point_light_radius,

intensity_r: 0.125,

intensity_g: 0.025,

intensity_b: 0.025

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: -1.0,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.9,

radius: point_light_radius,

intensity_r: 0.25,

intensity_g: 0.25,

intensity_b: 0.25

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: 1.0,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.9,

radius: point_light_radius,

intensity_r: 0.25,

intensity_g: 0.25,

intensity_b: 0.25

}

);

Now it's time to upload this data to GPU.

UBO copy

First we upload it into the light data array.

//

// Uniform upload

//

{

// ...

// Filling them with data

// ...

for (i, light) in lights.iter().enumerate()

{

light_data_array[i] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

LightData {

position: [

light.x,

light.y,

light.z,

light.radius

],

intensity: [

light.intensity_r,

light.intensity_g,

light.intensity_b,

0.0

]

}

);

}

// ...

}

From there the shader can use the radius for the diffuse and specular lighting calculations.

Then we upload it to light transform.

//

// Uniform upload

//

{

// ...

// Filling them with data

// ...

let light_transform_data_array = &mut transform_data_array[static_meshes.len()..static_meshes.len() + lights.len()];

for (i, light) in lights.iter().enumerate()

{

light_transform_data_array[i] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

TransformData {

model_matrix: mat_mlt(

&translate(

light.x,

light.y,

light.z

),

&scale(

light.radius,

light.radius,

light.radius

)

)

}

);

}

let light_material_data_array = &mut material_data_array[static_meshes.len()..static_meshes.len() + lights.len()];

for (i, light) in lights.iter().enumerate()

{

let mlt = 1.0 / (light.radius * light.radius);

light_material_data_array[i] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

MaterialData {

albedo: [

0.0,

0.0,

0.0,

0.0

],

roughness: 0.0,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.0,

std140_padding_0: 0.0,

emissive: [

light.intensity_r * mlt,

light.intensity_g * mlt,

light.intensity_b * mlt,

0.0

]

}

);

}

}

This way we will see the radius of the sphere lights. For the emissive lighting, we use the sphere radius to spread the radiant intensity out.

Now let's utilize the newly uploaded light radius in our fragment shader!

Shader programming

Here we implement the diffuse and specular lighting approaches that we discussed at the beginning of the chapter.

#version 460

const float PI = 3.14159265359;

const uint MAX_TEX_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 3;

const uint MAX_CUBE_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 2;

const uint MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 8;

const uint MAX_OBJECT_COUNT = 64;

const uint MAX_LIGHT_COUNT = 64;

const uint ENV_MAP_INDEX = 1;

const uint DFG_TEX_INDEX = 0;

const uint OBJ_TEXTURE_BBEGIN = 1;

layout(set = 0, binding = 1) uniform sampler2D tex_sampler[MAX_TEX_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

layout(set = 0, binding = 4) uniform samplerCube cube_sampler[MAX_CUBE_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

const uint ROUGHNESS = 0;

const uint METALNESS = 1;

const uint REFLECTIVENESS = 2;

struct MaterialData

{

vec4 albedo_fresnel;

vec4 roughness_mtl_refl;

vec4 emissive;

};

struct LightData

{

vec4 pos_and_radius;

vec4 intensity;

};

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 2) uniform UniformMaterialData {

float exposure_value;

vec3 camera_position;

MaterialData material_data[MAX_OBJECT_COUNT];

} uniform_material_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 3) uniform UniformLightData {

uint light_count;

LightData light_data[MAX_LIGHT_COUNT];

} uniform_light_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

layout(push_constant) uniform ResourceIndices {

uint obj_index;

uint ubo_desc_index;

uint texture_id;

} resource_indices;

layout(location = 0) in vec3 frag_position;

layout(location = 1) in vec3 frag_normal;

layout(location = 2) in vec2 frag_tex_coord;

layout(location = 0) out vec4 fragment_color;

vec4 fresnel_schlick(vec4 fresnel, float camera_dot_half)

{

return fresnel + (1.0 - fresnel) * pow(max(0.0, 1.0 - camera_dot_half), 5);

}

float trowbridge_reitz_dist_sphere(float alpha, float alpha_prime, float normal_dot_half)

{

float alpha_sqr = alpha * alpha;

float normal_dot_half_sqr = normal_dot_half * normal_dot_half;

float div_sqr_part = (normal_dot_half_sqr * (alpha_sqr - 1) + 1);

float alpha_prime_sqr = alpha_prime * alpha_prime;

float norm = alpha_sqr / (alpha_prime_sqr);

return norm * alpha_sqr / (PI * div_sqr_part * div_sqr_part);

}

float smith_lambda(float roughness, float cos_angle)

{

float cos_sqr = cos_angle * cos_angle;

float tan_sqr = (1.0 - cos_sqr)/cos_sqr;

return (-1.0 + sqrt(1 + roughness * roughness * tan_sqr)) / 2.0;

}

void main()

{

uint texture_id = resource_indices.texture_id;

uint obj_index = resource_indices.obj_index;

uint ubo_desc_index = resource_indices.ubo_desc_index;

// Lighting

vec3 normal = frag_normal;

if (!gl_FrontFacing)

{

normal *= -1.0;

}

normal = normalize(normal);

vec3 camera_position = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].camera_position.xyz;

vec3 camera_direction = normalize(camera_position - frag_position);

float camera_dot_normal = dot(camera_direction, normal);

vec4 albedo_fresnel = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].material_data[obj_index].albedo_fresnel;

float roughness = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].material_data[obj_index].roughness_mtl_refl[ROUGHNESS];

float metalness = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].material_data[obj_index].roughness_mtl_refl[METALNESS];

float reflectiveness = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].material_data[obj_index].roughness_mtl_refl[REFLECTIVENESS];

vec4 tex_color = texture(tex_sampler[OBJ_TEXTURE_BBEGIN + texture_id], frag_tex_coord);

vec3 diffuse_brdf = albedo_fresnel.rgb * tex_color.rgb / PI;

vec3 radiance = vec3(0.0);

for (int i=0;i < uniform_light_data[ubo_desc_index].light_count;i++)

{

vec3 light_position = uniform_light_data[ubo_desc_index].light_data[i].pos_and_radius.xyz;

float light_radius = uniform_light_data[ubo_desc_index].light_data[i].pos_and_radius.w;

vec3 light_intensity = uniform_light_data[ubo_desc_index].light_data[i].intensity.rgb;

vec3 light_direction = light_position - frag_position;

float light_dist_sqr = dot(light_direction, light_direction);

light_direction = normalize(light_direction);

// Diffuse

float beta = acos(dot(normal, light_direction));

float dist = sqrt(light_dist_sqr);

float h = dist / light_radius;

float x = sqrt(h * h - 1);

float y = -x * (1 / tan(beta));

float form_factor = 0.0;

if(h * cos(beta) > 1.0)

{

form_factor = cos(beta) / (h * h);

}

else

{

form_factor = (1 / (PI * h * h)) * (cos(beta) * acos(y) - x * sin(beta) * sqrt(1.0 - y * y)) + (1.0 / PI) * atan(sin(beta) * sqrt(1.0 - y * y) / x);

}

vec3 light_radiance = light_intensity / (light_radius * light_radius);

vec3 irradiance = light_radiance * PI * max(0.0, form_factor);

vec3 diffuse_radiance = diffuse_brdf * irradiance;

// Specular

vec3 reflection_vector = reflect(camera_direction, normal);

vec3 light_to_surface = frag_position - light_position;

vec3 light_to_ray = light_to_surface - dot(light_to_surface, reflection_vector) * reflection_vector;

float light_to_ray_len = length(light_to_ray);

light_position = light_position + light_to_ray * clamp(light_radius / light_to_ray_len, 0.0, 1.0);

light_direction = (light_position - frag_position);

light_dist_sqr = dot(light_direction, light_direction);

light_direction = normalize(light_direction);

vec3 half_vector = normalize(light_direction + camera_direction);

float normal_dot_half = dot(normal, half_vector);

float camera_dot_half = dot(camera_direction, half_vector);

float light_dot_normal = dot(normal, light_direction);

float light_dot_half = dot(light_direction, half_vector);

float alpha = roughness * roughness;

float alpha_prime = clamp(alpha + light_radius/(2.0*sqrt(light_dist_sqr)), 0.0, 1.0);

vec4 F = fresnel_schlick(albedo_fresnel, camera_dot_half);

float D = trowbridge_reitz_dist_sphere(alpha, alpha_prime, normal_dot_half);

float G = step(0.0, camera_dot_half) * step(0.0, light_dot_half) / (1.0 + smith_lambda(roughness, camera_dot_normal) + smith_lambda(roughness, light_dot_normal));

vec4 specular_brdf = F * D * G / (4.0 * max(1e-2, camera_dot_normal));

vec3 metallic_contrib = specular_brdf.rgb;

vec3 non_metallic_contrib = vec3(specular_brdf.a);

vec3 specular_coefficient = mix(non_metallic_contrib, metallic_contrib, metalness);

vec3 specular_radiance = specular_coefficient * step(0.0, light_dot_normal) * light_intensity / light_dist_sqr;

radiance += mix(diffuse_radiance, specular_radiance, reflectiveness);

}

vec3 emissive = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].material_data[obj_index].emissive.rgb;

radiance += emissive;

// Environment mapping

vec3 env_tex_sample_diff = textureLod(cube_sampler[ENV_MAP_INDEX], normal, textureQueryLevels(cube_sampler[ENV_MAP_INDEX])).rgb;

vec3 env_tex_sample_spec = textureLod(cube_sampler[ENV_MAP_INDEX], normal, roughness * textureQueryLevels(cube_sampler[ENV_MAP_INDEX])).rgb;

vec2 dfg_tex_sample = texture(tex_sampler[DFG_TEX_INDEX], vec2(roughness, camera_dot_normal)).rg;

vec4 env_F = albedo_fresnel * dfg_tex_sample.x + dfg_tex_sample.y;

vec3 env_diff = diffuse_brdf * env_tex_sample_diff;

vec3 env_spec = mix(env_F.a * env_tex_sample_spec, env_F.rgb * env_tex_sample_spec, metalness);

vec3 final_env = mix(env_diff, env_spec, reflectiveness);

radiance += final_env;

// Exposure

float exposure_value = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].exposure_value;

float ISO_speed = 100.0;

float lens_vignetting_attenuation = 0.65;

float max_luminance = (78.0 / (ISO_speed * lens_vignetting_attenuation)) * exp2(exposure_value);

float max_spectral_lum_efficacy = 683.0;

float max_radiance = max_luminance / max_spectral_lum_efficacy;

float exposure = 1.0 / max_radiance;

vec3 exp_radiance = radiance * exposure;

// Tone mapping

float a = 2.51f;

float b = 0.03f;

float c = 2.43f;

float d = 0.59f;

float e = 0.14f;

vec3 tonemapped_color = clamp((exp_radiance*(a*exp_radiance+b))/(exp_radiance*(c*exp_radiance+d)+e), 0.0, 1.0);

// Linear to sRGB

vec3 srgb_lo = 12.92 * tonemapped_color;

vec3 srgb_hi = 1.055 * pow(tonemapped_color, vec3(1.0/2.4)) - 0.055;

vec3 srgb_color = vec3(

tonemapped_color.r <= 0.0031308 ? srgb_lo.r : srgb_hi.r,

tonemapped_color.g <= 0.0031308 ? srgb_lo.g : srgb_hi.g,

tonemapped_color.b <= 0.0031308 ? srgb_lo.b : srgb_hi.b

);

fragment_color = vec4(srgb_color, 1.0);

}

First let's rename the position field of the LightData struct to pos_and_radius to

better reflect its content.

Then we upload the new formula for diffuse lighting. We calculate the view factor following the view factor formula. Then we calculate all of the incoming irradiance from the sphere light by spreading out the radiant intensity across the visible area of the sphere. Then we multiply it with the diffuse BRDF to get the reflected diffuse radiance.

Then comes the specular lighting. First we calculate the representative point (which is the closest to the line of the

mirror direction), and then pretty much do the same thing that we did with a point light, except for the normalization.

Let's remember that we chose a new for the normalization and we included

a formula for it. This new roughness is stored in alpha_prime. The Trowbridge-Reitz distribution with the

new normalization factor is in the trowbridge_reitz_dist_sphere function. We simply calculate the

normalization factor and multiply the distribution with it. Then we just do what we originally did.

Finally we blend the diffuse and specular reflected radiance, and we are happy.

I saved this file as 06_sphere_light.frag.

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/06_sphere_light.frag.spv ./shader_src/fragment_shaders/06_sphere_light.frag

Once our binary is ready, we need to load.

//

// Shader modules

//

// ...

// Fragment shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/06_sphere_light.frag.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

// ...

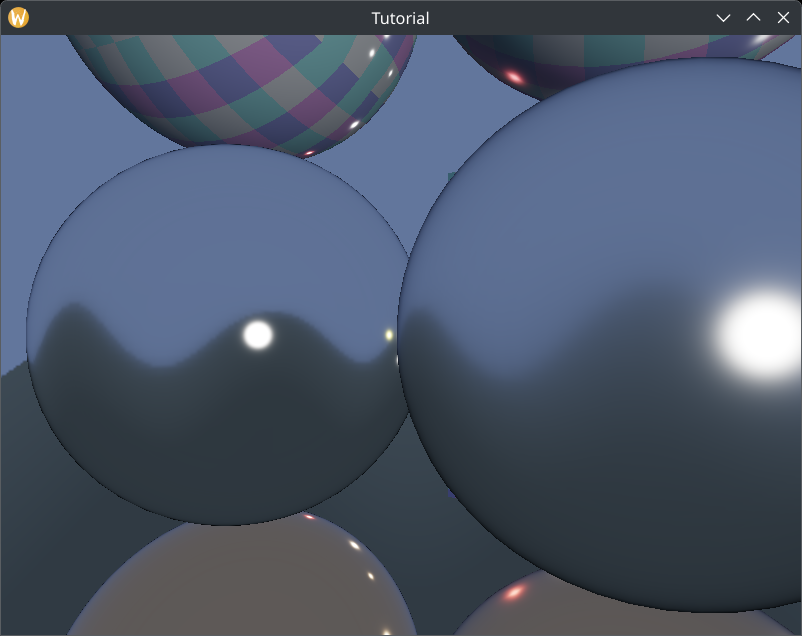

...and that's it! Our application finally has sphere lights.

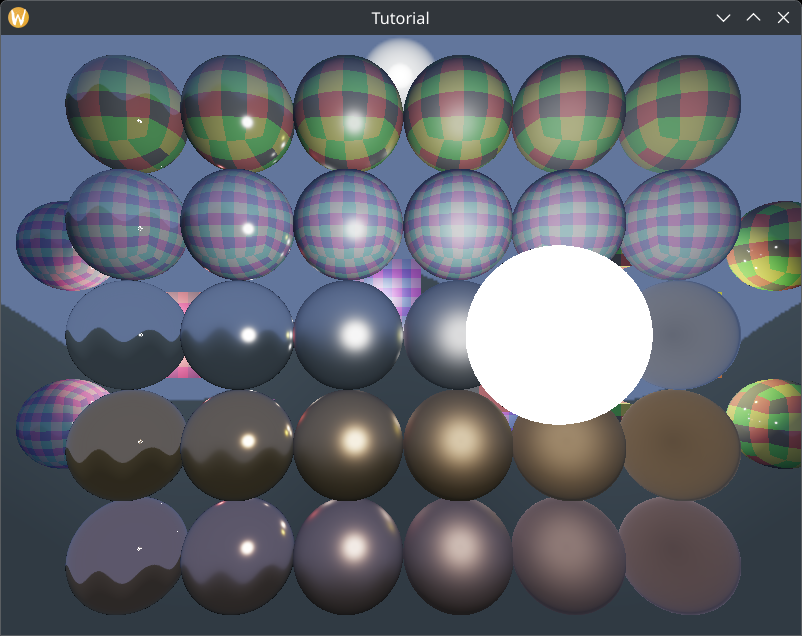

Adjusting roughness

There are artifacts with the minimum roughness value that we chose in the specular lighting chapter. The reflections look ugly. Probably floating point rounding errors.

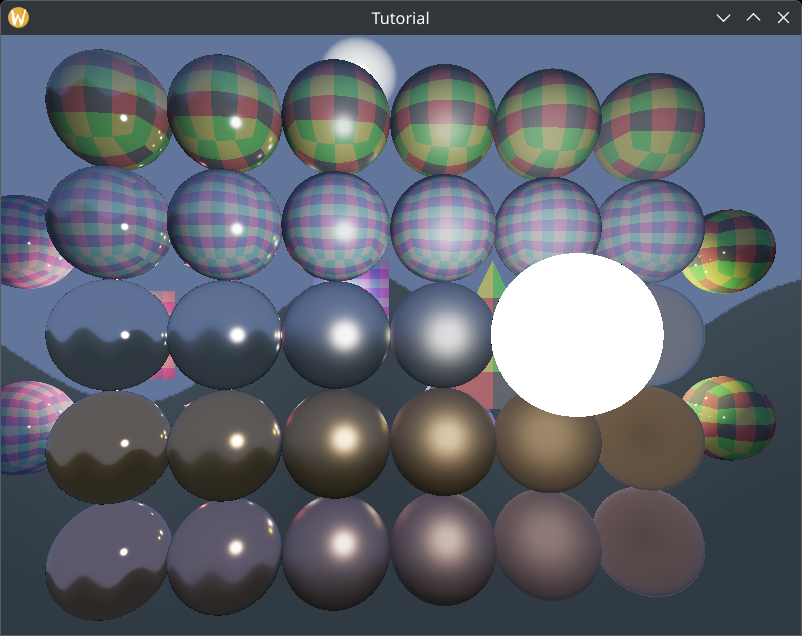

I tried it with this roughness parameter.

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

//let min_roughness: f32 = 0.01;

let min_roughness: f32 = 0.1;

Now it looks pretty!

Wrapping up

Now we have sphere lights in our application, and we have taken a step from "PBR being viable" to "PBR being good". Finally we have gotten rid of the tiny specular highlights that point lights gave.

Of course point lights are not always bad. In a real world application small and distant sphere lights can be approximated well with point lights and they're faster than sphere lights, so that approach isn't useless either. In a real world application you should support both types.

In the next chapter we will implement another useful feature, eye adaptation. So far our exposure value is uploaded from the application and can be adjusted manually, but you may need to render a scene where determining the exposure value based on the rendered image saves artist time.

The sample code for this tutorial can be found here.

The tutorial continues here.