3D

In the previous chapter we added texturing to our application, but it was still a 2D application.

Many people want to create 3D applications, and that requires some math. You will need to deal with 3D coordinates, it is useful if you know how to move, rotate and scale objects in 3D, and you will need to project vertices onto the 2D screen in a way that it gives the illusion of a 3D geometry.

In this chapter we will have a superficial introduction to 3D vectors, transformations in 3D space and perspective projection.

This part of the tutorial is more math heavy than the previous ones. There is no universal good way of digesting it. Some peolpe learn better from example code, and gain better understanding of the maths by understanding code. Some people might desire a proper theoretical explanation first. There are multiple ways to consume this material and one might be more suitable for you than the other depending on your background:

- Read and understand the math first, then the code

- Understand the code first, and then interpret the math

Read whichever way is better for you. Be prepared that multiple rereads may be necessary.

Also I cannot define every linear algebra term in this chapter, only a few, so if you encounter a term you do not understand, such as vector space or linear combination, you may need to google it or read about it in a linear algebra book.

This tutorial is in open beta. There may be bugs in the code and misinformation and inaccuracies in the text. If you find any, feel free to open a ticket on the repo of the code samples.

3D and projection

In 2D we had 2D coordinates to define a position. We defined more complicated geometry with a list of 2D vertices and defined triangles between them. When we created a scene representation, we intorduced some very simple transformations for scene elements.

In 3D we need 3D coordinates. The trivial part of 3D is using 3D coordinates: just adding a third component. A slightly less trivial part is introducing a scene representation, because the conventional way of storing per scene element transformations involves a bit of extra math. The absolutely nontrivial part is mapping 3D vectors to the 2D screen. In the end the swapchain images are 2D images, and you need to arrange 2D triangles in a way that it gives the illusion of a 3D object.

Let's get inspired on how to do that. Who are the ones who also create 2D images giving a 3D illusion? Artists!

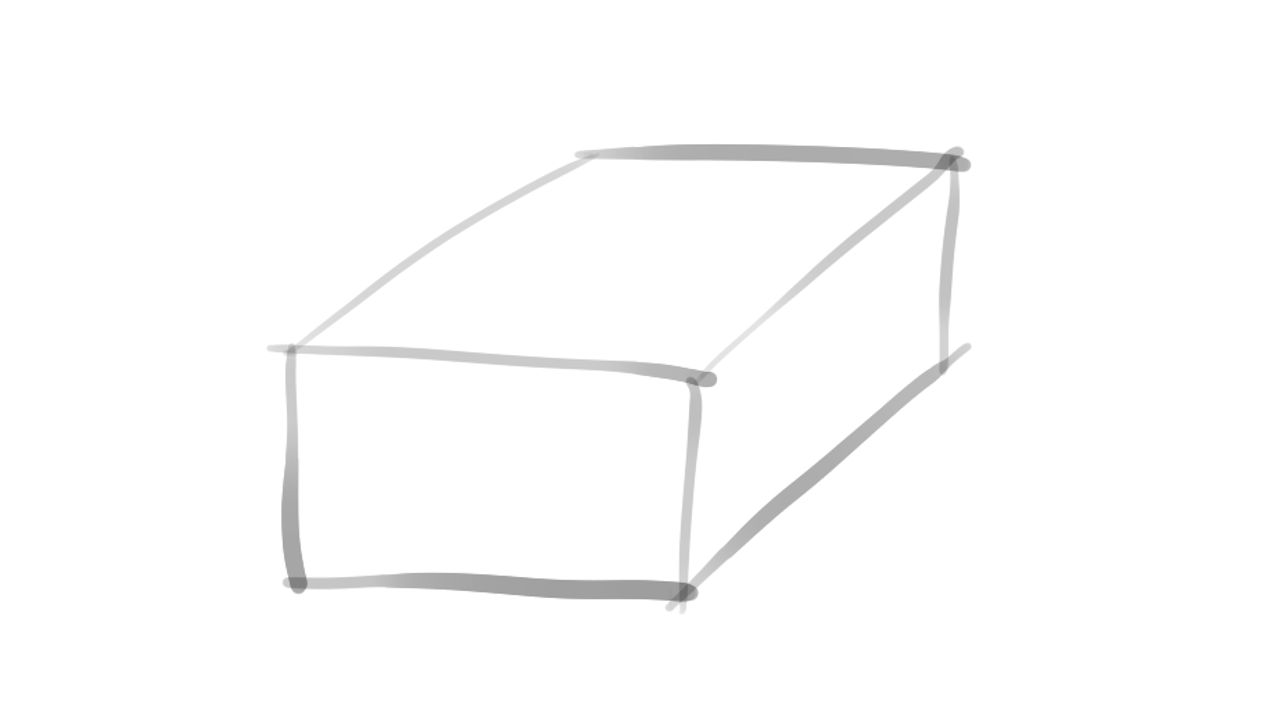

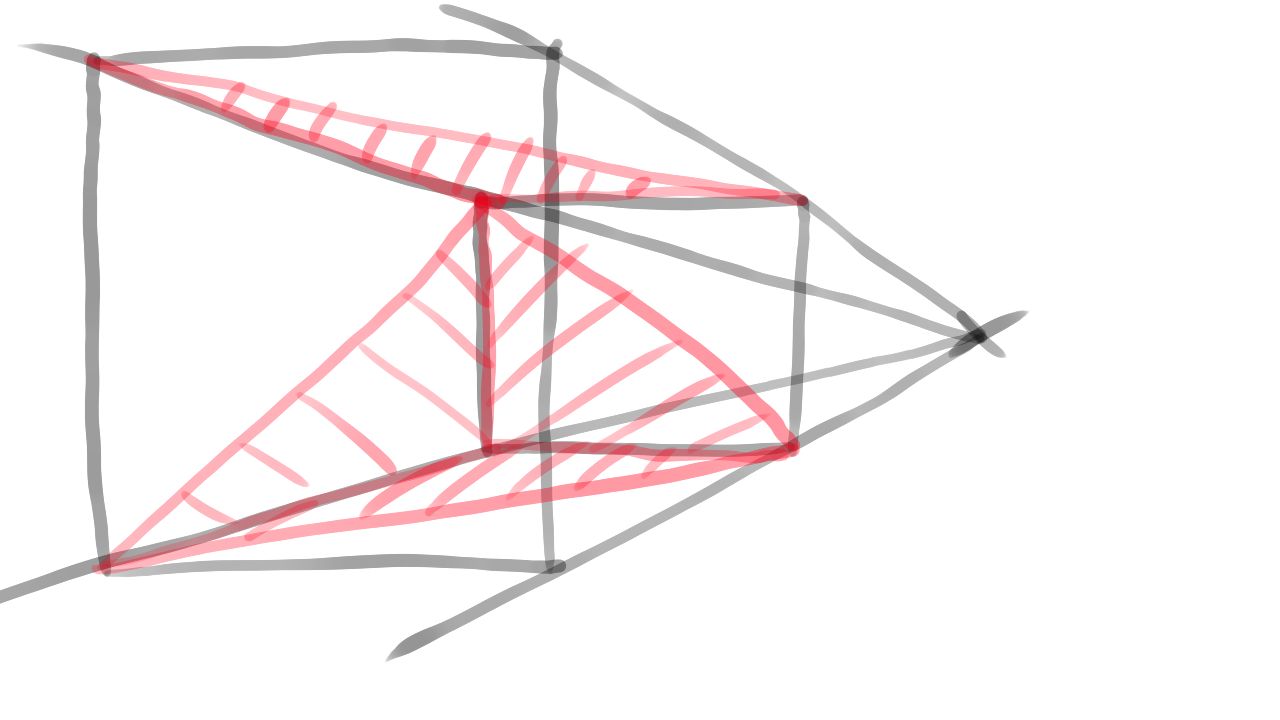

Let's talk about how they create the illusion of 3D geometry on a 2D surface. If you didn't study perspective, you may still have figured out that if you draw a rotated cube, and you draw its sides, you can kind of make it look 3D, like the drawing below. This is called orthographic projection.

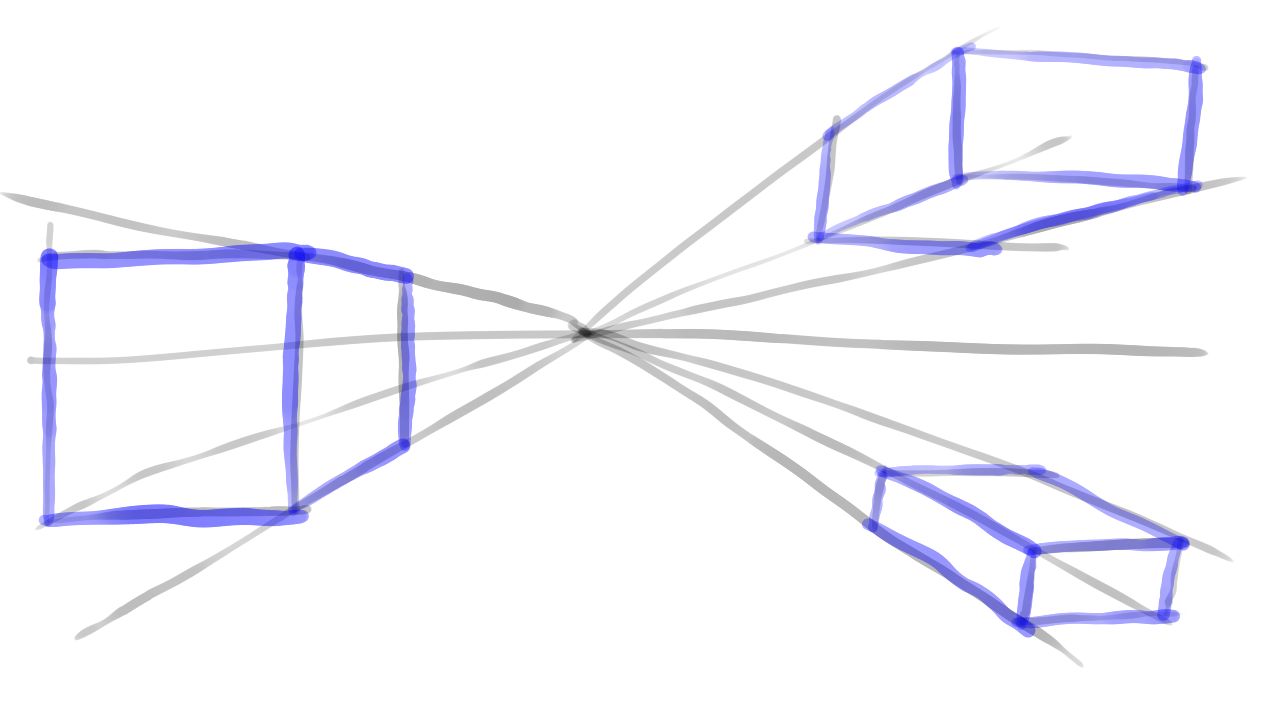

The problem is, this approach leaves out something important: things farther away need to get smaller, and closer things need to get bigger. Actually the closer face of a cube needs to be bigger than the one farther away. Artists use the concept of perspective and perspective projection to reach a similar effect.

They draw the horizon line. Everything above the horizon line is above the eye, and everything below is below the eye. They choose a point in the distance called the vanishing point. As things get farther along parallel lines looking forward, they all get closer to this vanishing point. You can draw guidelines from this vanishing point that represent parallel lines in the 3D world, and they will help you draw distant things smaller. Sometimes the parallel sides of a cube appear to have an angle between them, and that creates good 3D illusion.

If you want to draw using Vulkan in a way that gives the illusion of 3D, you want to mimic what artists are already doing, and this will be done with perspective projection. We will learn about its math as well in this chapter.

The theory part of this chapter will be the following:

- First we will talk about linear transformations, vectors and matrices. Linear transformations and matrices are very conventional and general purpose tools that help you create scene representations.

- Then we will talk about a few basic transformations.

- Then we will talk about perspective projection.

Linear transformations and matrices

Let and be vector spaces! A linear transformation is a mapping that satisfies the following two conditions:

One of the useful features of a linear transformation is that a set of transformed base vectors can be used to transform every vector written as a linear combination of these base vectors. Let's start assuming a 3D vector space, and let , and be our base vectors! We can write down a 3D vector as the linear combination of these base vectors like this:

If we transform with a linear transformation , we can use the conditions of linearity to move the additions and multiplication out of , and write down the transformed as the function of the transformed base vectors and the original , and coordinates.

There. A bit of reordering, and the transformed vector is written down as the linear combination of the transformed base vectors.

In our 3D case , and will be float tuples, as well as their transformed counterparts, so linear transformations are very convenient, because whole transformations can be stored as a few float arrays. This is only one step away from organizing these float arrays into 2D float tables, aka matrices.

Matrices are 2D tables of numbers. You can see an example of a 2x2 matrix below.

Matrices are useful is because there is a multiplication operation defined between them that will be useful for us. Let's see how matrix multiplication works between two 2x2 matrices, and let's try to interpret what we see. The multiplication can be seen below.

This is a generic formula of multiplying two 2x2 matrices. The result will be another 2x2 matrix. You can create bigger matrices, and the formula for them would be similar. Check out the linked Wikipedia article for the generic formula!

Let's observe the resulting matrix and notice some patterns!

- The resulting cell in row i and columnt j looks like as if we took the ith row of the first matrix, the jth column of the second matrix, pretended that they are vectors, and calculated their dot product.

- The resulting column j looks like as if we pretended that the columns of the first matrix are vectors, and took their linear combination with the cells of column j of the second matrix.

Matrices do not have to be of the same dimensions to multiply them together. For instance you can multiply a 2x2 and a 2x1 matrix together like this:

You cannot multiply arbitrary matrices together, but you can multiply matrices of MxN and NxP dimensions. So the column count of the first matrix and the row count of the second matrix must match. The resulting matrix will be a matrix with MxP dimensions. In the previous example a 2x1 matrix.

Now pay attention to a familiar pattern! If we pretended that the columns of the first matrix were vectors, the result would look like as if it were their linear combination. Beyond that we could pretend that the second matrix and the resulting marix were in fact just vectors.

This means that we can put vectors into the columns of matrices, and put vectors into single column matrices, and performing matrix multiplications will perform linear combinations! Also remember, that performing a linear transformation could be done by taking the linear combination of transformed vectors using the coordinates of the vector we wanted to transform. Now we can realize, that we can represent a linear transformation with a matrix whose columns are the transformed base vectors, and perform a linear transformation with matrix multiplication.

Actually, multiplying matrices together is meaningful as well. The resulting matrix will perform the transformation of the individual matrices one after another. Let's have two matrices, and let's transform a vector with both of them, one after another! Let's name the resulting vector ! The equation would be the following:

The transformation of the matrix closer to the vector will be applied first, and the one further away will be applied later. If we premultiplied our matrices in this order, we would get a new matrix that applies both transformations in the same order. This is illustrated on the following equations:

Just be careful, matrix multiplication is not commutative! If you swap matrix multiplications, the order of transforms will swap as well, and the result will not be the same. Equation 1 shows a new matrix being created by multiplying the original two together in the same order. Equation 2 uses this new matrix. The results will be the same as before.

Now that we had a mini introduction to linear transformations and matrices, let's talk about a few fundamental 3D transformations!

Basic transformations

In the previous examples we have seen 2x2 matrices and 2D vectors put into 2x1 matrices. Matrix multiplication is defined for larger matrices as well, so you can use the same princpile for 3D as well, just for now you will need 3x3 matrices for transformations and 3x1 matrices for vectors.

Let's talk about a few useful transformations that you will carry with you for the rest of your life.

At first let's have 3D vectors and the following three base vectors:

If you want to transform a 3D vector , you need to write it down as the linear combination of these base vectors:

Now we just transform our base vectors, put them into matrices, and we will get our basic transformation matrices.

Let's start with scaling! If you wanted to scale coordinates with , coordinates with and coordinates with , you would transform your base vectors like this:

We would put these vectors into the columns of a matrix like this:

This will be your scaling matrix. If you look at wikipedia, you can find the exact same matrix.

Rotation around one of the axis happens similarly. Rotating around the X axis by angle involves leaving the base vector parallel to X unchanged, and rotating the other two using and . The resulting matrix will look like this:

Rotation around Y happens using the same principles. Its matrix will be the following:

You can do the rotation around the Z axis as a homework or copy the matrix from wikipedia. That will be useful in the future as well.

You cannot perform translation using 3D vectors and 3x3 matrices, but you can hack the system by using 4x4 matrices, and extending every 3D vector with a fourth component which will be set to 1. The extended 3D vectors and the translation matrix will be the following:

As a homework you can multiply the translation matrix above with the extended 3D vector above and see that it indeed performs a translation.

The rest of the transformations can be used with a fourth coordinate as well, you just need to extend them.

Now let's code! We already know that we will need 4x4 matrices to be able to represent and perform all of the aforementioned transformations and more. We can use a simple float array to store a 4x4 matrix. The array must have 16 elements. The first 4 elements will contain our first column, the second 4 elements will contain our second column, the third 4 elements will contain our third column, and the fourth will contain our fourth column.

Visually this may going to confuse you, because it will appear as if the matrices were mirrored diagonally, but they will be interpreted by the shaders as if 4 consecutive floats were a single column.

We must be very conscious about our memory layout, because we will upload these to the GPU, and the memory layouts must correspond to shader variables. The layout I gave you earlier will work well with GLSL shaders.

Let's write a function for the previously mentioned transformations as well!

Here is the function for translation:

//

// Math

//

// ...

fn translate(x: f32, y: f32, z: f32) -> [f32; 16]

{

[

1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0,

x, y, z, 1.0

]

}

// ...

Again: it looks weird, it looks like as if I mirrored it diagonally, but don't let this confuse you! Shaders will interpret it the way we talked about.

Here is the function for scaling:

//

// Math

//

// ...

fn scale(x: f32, y: f32, z: f32) -> [f32; 16]

{

[

x, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, y, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, 0.0, z, 0.0,

0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0

]

}

// ...

Here are our rotation matrices.. We will only rotate around the X and Y axis, rotation around Z will be your homework if you need it.

//

// Math

//

// ...

fn rotate_x(angle: f32) -> [f32; 16]

{

[

1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, angle.cos(), angle.sin(), 0.0,

0.0, -(angle.sin()), angle.cos(), 0.0,

0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0

]

}

fn rotate_y(angle: f32) -> [f32; 16]

{

[

angle.cos(), 0.0, -(angle.sin()), 0.0,

0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

angle.sin(), 0.0, angle.cos(), 0.0,

0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0

]

}

// ...

We will also want matrices that perform a series of these transformations, so let's write a matrix multiplication function!

//

// Math

//

fn mat_mlt(a: &[f32; 16], b: &[f32; 16]) -> [f32; 16]

{

let mut result = [0.0; 16];

for i in 0..4

{

for j in 0..4

{

result[i*4 + j] = b[i*4 + 0]*a[j + 0] +

b[i*4 + 1]*a[j + 4] +

b[i*4 + 2]*a[j + 8] +

b[i*4 + 3]*a[j + 12];

}

}

result

}

// ...

When we multiplied matrices, one matrix was on the left, and one was on the right.

In this function a will be the matrix on the left, and b will be the matrix on the

right. The value of the cell in the ith column and jth row was calculated the following way: we took the jth

row of a, the ith column of b, pretended that they are vectors, and calculated

their dot product. In other words, we performed a component-wise multiplication and summed the resulting

values together.

The ith column of b following the agreed upon memory layout is

[b[i*4 + 0], b[i*4 + 1], b[i*4 + 2], b[i*4 + 3]] The jth row of a will be

[a[j + 0], a[j + 4], a[j + 8], a[j + 12]] What we see in the innermost loop is exactly what we

described: we mulltiply these vectors component-wise and sum the resulting values together. We place it in the

result's cell in the ith column and jth row, and this performs our matrix multiplication.

Perspective projection

So far we have figured out how to move, rotate and scale objects in our 3D world, but we still have a missing piece: how to map 3D coordinates to the screen in a way that gives the illusion of 3D. The same one we talked about when we have drawn the horizon, a vanishing point, "parallel lines" meeting in that vanishing point and so on.

We can find the video presentations of the Computer Graphics course the Budapest University of Technology and Economics. The speaker is László Szirmay-Kalos and he uploaded the presentations to youtube. The one we are curious about (with timestamp) is this one. At the timestamp he illustrates central projection, which we can use to map our 3D vectors onto the 3D screen the desired way.

To figure out how to do central projection let's go to a coordinate system where the origin will be the position of the camera, and the positive Z axis will align with the camera's view direction! Let's have a clipping plane at 1 unit distance from the origin along the Z axis, perpendicular to the Z axis! Then let's have a vertex that is visible to the camera! We want to project this to the clipping plane obtaining the vector .

Let's create a drawing so we can see what I am talking about! You will see a 2D cross section of our 3D screen in the YZ plane. The principles for the XZ plane and the x coordinates will be the same.

So we have the following vector :

And we would like to project this to the following vector :

Let's look at the diagram and observe what we need to do: we need to draw a line from the origin to , and will be the intersection of this line and the clipping plane. On the 2D cross section we can see that we have two similar triangles. One triangle has a side parallel to the Z axis whose length is . The same side of the other one has length . The ratio between them is . Since the two triangles are similar, the ratio between and will be the same, and the same will apply to the X coordinates as well. The operation we are looking for is the following:

So we would need to divide every coordinate with . The projection we are looking for can be done by dividing with the z coordinate. We could just do this within our vertex shader and it would work, but people have extended our hacky "four component 3D vectors" to be able to handle division by a coordinate, letting us represent projections with matrices as well, and these will be homogeneous coordinates.

Homogeneous coordinates

Previously in order to translate with 4x4 matrices we hacked our 3D coordinate system: we added a fourth coordinate and set it to 1. Let's extend this even further!

Instead of assigning a single 4D vector to our 3D vectors, let's assign infinite 4D vectors to them the following way: Let every 3D coordinate be represented by the 4D vector for every real number ! Basically take the original hacky 4D vector, and say that if you multiply all four coordinates with any real number , it still represents the same 3D vector!

These will be our homogeneous coordinates.

If for any 4D vector we want to get our 3D vector back, we just divide every coordinate with the fourth coordinate , and we get our vector back. This step will be called the homogeneous division.

Why is this good? Because you can use a matrix to copy the Z coordinate to the fourth component, and the homogeneous division will result in a central projection! For instance the following matrix will copy the z coordinate to the fourth column:

Taking our previous vector and representing it with homogeneous coordinates...

If we multiply this with the matrix, we get...

After performing the homogeneous division we get...

...and these are the homogeneous coordinates of our centrally projected vector! The matrix is a central projection matrix! We are on the right track! Homogeneous coordinates allow us to perform projections using a matrix!

Now we understand why gl_Position is a 4 dimensional vector: it represents homogeneous coordinates.

After our vertex shader runs, the homogeneous division is done and our primitives get rasterized. Projection can

be done using the fourth coordinate, and this is how we will do 3D graphics with Vulkan. For the sake of

completeness let's also mention that in GLSL the fourth coordinate is called w, so gl_Position

looks like this:

Now let's create a little bit more refined matrix that does a bit of extra work beyond projection!

Projection matrix

We used the ratio between similar triangles to figure out how to project our vertices onto the screen: by dividing with the z coordinate. We introduced homogeneous coordinates to represent projection with a matrix. Now it's time to add a bit of extra to that matrix to finally get a bit closer to the projection matrix generally found in the literature.

The first feature we want to add to our projection matrix is dividing the x coordinate with the aspect ratio. We did this in the uniform buffer tutorial as well to make sure that resizing the window will not distort our image.

The other bit of extra that we need to use is adjustable field of view. In the simplest sense the field of view parameter controls how big the clipping plane is. The conventional parameter to use is the angle between the Z axis and the top of the clipping plane.

If we place our clipping plane 1 unit from the origin along the Z axis, and the field of view angle is the height of the clipping plane equals to . The relationship between the field of view angle and the clipping plane height is illustrated below.

The value written to gl_Position must be in normalized device coordinates, so the x and

y coordinates must be between

. If the clipping plane's height is

,

then the visible y coordinates after projection will be in the

range. A division by

will scale the y coordinates into the correct range.

The operation for the x coordinates will be similar, but there we need to scale with the aspect ratio as well. If the aspect ratio is , the width of the clipping plane will be , so this is what we need to divide with.

Now let's construct the matrix! We want to do the following:

- Divide the x coordinates with .

- Divide the y coordinates with .

- Copy the z coordinate to the w coordinate to make sure that the homogeneous division projects our 3D vector.

We know how to do these piece by piece: by scaling and projecting. After putting it together the matrix will be the following:

This is not the projection matrix found in the literature. This one is still incomplete! The fourth column will move the z coordinate into the w coordinate. Since we do not yet care about the z coordinate, we can just zero it all out with the third column. This will cause problems later, but that will be corrected in the next chapter.

The resulting function will be named shitty_perspective:

//

// Math

//

// ...

fn shitty_perspective(field_of_view_angle: f32, aspect_ratio: f32) -> [f32; 16]

{

let tan_fov = (field_of_view_angle / 2.0).tan();

let m00 = 1.0 / (aspect_ratio * tan_fov);

let m11 = 1.0 / tan_fov;

[

m00, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, m11, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0

]

}

Why is it shitty? Because like I said zeroing out the z coordinate will cause problems that we need to fix later, but for now this matrix will at least do the projection.

Model, View and Projection matrix

In the uniform buffer tutorial we introduced a 2D scene and a few related concepts. Here we are going to revisit the topic and adapt our scene representation to 3d.

Previously introduced object space, which was the coordinate system where our model was defined. When we wanted to create multiple instances of the same model, we introduced world space, which was a new coordinate system where our scene was defined. We had multiple scene objects, each having a model and a transformation. We rendered every scene object by identifying its model, transforming every vertex of the model from object space to world space and rendering its triangles connecting these transformed vertices.

In our 2D scene we used a very specific data structure containing only a translation and a uniform scaling factor to represent our object transforms. In 3D the conventional way of doing it is a matrix.

A model matrix is a matrix defining the transformation of a scene object from object space to world space.

Now that we have scene elements with their models and transforms defined in world space, we want to render parts of it from a camera's point of view. This called for a new coordinate system, view space, where the origin was in the camera's position, and the axes were aligned with the camera's "up", "forward", etc. directions. The camera had a transformation in world space, and we used it to move the scene elements from world space to view space.

In our 2D scene the analogous data was -1 times the camera's position. In 3D where a camera can be rotated as well, conventionally this transformation is also represented by a matrix.

A view matrix is a matrix defining the transformation from world space to view space.

Then finally we had to apply a final transformation to move vertices from view space to normalized device coordinates, where Vulkan needs them to be.

In our 2D scene this was nothing more than dividing the x coordinate with the aspect ratio, and we just combined this with our camera transform. In 3D we are going to do more: perform the projection, divide the x and y coordinates by the dimensions of our clipping plane, and conventionally this is also represented by a matrix.

A projection matrix is a matrix defining the transformation from view space to normalized device coordinates.

From these primitives we are going to build a new scene representation for our 3D scenes on our GPU: we will create a model matrix for every scene object and a view and a projection matrix for our camera.

3D models and scene

Now that we covered the math needed for 3D, it's time to adjust our model and scene representations.

Adding a third component

So far our models were 2D models and their vertices had two coordinates. In 3D we will need three coordinates.

First we add a third coordinate to the prepared data that we upload. We have a 2D triangle and a quad. In 3D they

are still going to be a triangle and a quad, but they will reside in the Z plane, having a 0.0 z

coordinate.

//

// Vertex and Index data

//

let vertices: Vec<f32> = vec![

// Triangle

// Vertex 0

-1.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

1.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 1

1.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 2

0.0, 1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 2

0.5, 1.0,

// Quad

// Vertex 0

-1.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

1.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 1

1.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 2

1.0, 1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

-1.0, 1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 3

0.0, 1.0

];

// ...

There. Now every position coordinate has a third component set to zero.

Then we modify our pipeline. We adjust the stride of our binding, the offset of the texture coordinates and the format of the vertex coordinates.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let vertex_bindings = [

VkVertexInputBindingDescription {

binding: 0,

stride: 5 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>() as u32,

inputRate: VK_VERTEX_INPUT_RATE_VERTEX,

}

];

let vertex_attributes = [

VkVertexInputAttributeDescription {

location: 0,

binding: 0,

format: VK_FORMAT_R32G32B32_SFLOAT,

offset: 0,

},

VkVertexInputAttributeDescription {

location: 1,

binding: 0,

format: VK_FORMAT_R32G32_SFLOAT,

offset: 3 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>() as u32,

}

];

// ...

First off we modified our stride, because now every vertex has 3 floats for position and 2 floats for texture

coordinates. These take 5 floats, so the stride must be 5 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>().

Then we modify our position attribute. We want to read 3 floats into a 3D vector in shader, and the corresponding

format will be VK_FORMAT_R32G32B32_SFLOAT.

Bookkeeping for models and textures

Now we are going to create a test scene with many instances of the same model, and to make that manageable, it's time to store the draw parameters of our models. When we added a quad next to the triangle and introduced our mesh pool-like vertex and index buffer design, we have already seen that the vertex offset, index count and first index parameters of the draw call can identify our model. It's time to collect our uploaded models' parameters into an array, and identify models as an index from now on.

//

// Game state

//

//

// Model and Texture ID-s

//

// Models

struct Model

{

index_count: u32,

first_index: u32,

vertex_offset: i32

}

let triangle_index = 0;

let quad_index = 1;

let models = [

// Triangle

Model {

index_count: 3,

first_index: 0,

vertex_offset: 0

},

// Quad

Model {

index_count: 6,

first_index: 3,

vertex_offset: 3

}

];

// Textures

let red_yellow_green_black_tex_index = 0;

let blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index = 1;

// ...

In our game loop if we want to identify a model for a draw call, we can use the triangle_index and

quad_index to decide which model to use, index into this array and read the three parameters for the

draw call.

Camera and Object CPU data

Then we want to create our data structure to store our game state. We will have a movable camera and a list of scene objects that we may or may not going to manipulate. In the uniform buffer tutorial we only stored the data of the camera and the player character, and just hardcoded the rest during upload. This time things will be different. We store the parameters of the camera and every scene object, and upload every one of them during rendering. We start with defining our structs.

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

struct Camera

{

x: f32,

y: f32,

z: f32,

rot_y: f32,

rot_x: f32

}

struct StaticMesh

{

x: f32,

y: f32,

z: f32,

scale: f32,

rot_x: f32,

rot_y: f32,

texture_index: u32,

model_index: usize

}

// ...

The camera will be represented by its position and its rotation around the Y and X axes.

The name StaticMesh refers to the model being static, and not skeletal mesh, cloth, etc.

The scene objects will be represented by their position, their rotation around the Y and X axes, a uniform

scaling factor, their texture and their model index. This model index refers to the previously created draw call

parameter array, and the texture index refers to the descriptor array index that we upload into a push constant.

We will have a single camera and many scene objects. We will store our scene objects in a vector and the first scene element will be the player character that we will control using the keyboard.

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

let mut camera = Camera {

x: 0.0,

y: 0.0,

z: -0.25,

rot_y: 0.0,

rot_x: 0.0

};

let player_id = 0;

let mut static_meshes = Vec::with_capacity(max_object_count);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 0.25,

y: 0.0,

z: -1.25,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: triangle_index

}

);

// ...

We add several other scene objects as well.

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 0.25,

y: -0.25,

z: -2.0,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: triangle_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -0.25,

y: 0.25,

z: -3.0,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: quad_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 1.5,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.6,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: quad_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -1.5,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.6,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: quad_index

}

);

// ...

Camera and Object movement

Let's extend our existing input logic!

We have existing logic that moves the player or the camera along two axes with the keyboard. We will also rotate them around two axes using the keyboard!

We need to add a few booleans to remember whether those keys are pressed, so let's do that!

//

// Game state

//

// Input state

// ...

let mut obj_turn_left = false;

let mut obj_turn_right = false;

let mut obj_turn_up = false;

let mut obj_turn_down = false;

// ...

let mut cam_turn_left = false;

let mut cam_turn_right = false;

let mut cam_turn_up = false;

let mut cam_turn_down = false;

// ...

Let's control these using key events! So far we used the WASD keys to move the player. Now we will rotate

it around the Y axis with Q and E, and rotate it around the X axis with R and F. The camera was moved with

UHJK, and now it will be rotated around the Y axis with Z and I, and rotated around the X axis with O and L.

(If you do not have a QWERTZ keyboard, you probably want to change that sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::Z

to sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::Y.)

// ...

for event in event_pump.poll_iter()

{

match event

{

sdl2::event::Event::Quit { .. } =>

{

break 'main;

}

sdl2::event::Event::Window { win_event, .. } =>

{

// ...

}

sdl2::event::Event::KeyDown { keycode: Some(keycode), .. } =>

{

// ...

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::Q

{

obj_turn_left = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::E

{

obj_turn_right = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::R

{

obj_turn_up = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::F

{

obj_turn_down = true;

}

// ...

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::Z

{

cam_turn_left = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::I

{

cam_turn_right = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::O

{

cam_turn_up = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::L

{

cam_turn_down = true;

}

}

sdl2::event::Event::KeyUp { keycode: Some(keycode), .. } =>

{

// ...

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::Q

{

obj_turn_left = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::E

{

obj_turn_right = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::R

{

obj_turn_up = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::F

{

obj_turn_down = false;

}

// ...

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::Z

{

cam_turn_left = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::I

{

cam_turn_right = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::O

{

cam_turn_up = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::L

{

cam_turn_down = false;

}

}

_ =>

{}

}

}

// ...

Our data structures changed from four variables into two larger data structures, so let's modify our "game logic"!

//

// Logic

//

if obj_forward

{

static_meshes[player_id].z -= 0.01;

}

if obj_backward

{

static_meshes[player_id].z += 0.01;

}

if obj_left

{

static_meshes[player_id].x -= 0.01;

}

if obj_right

{

static_meshes[player_id].x += 0.01;

}

if obj_turn_left

{

static_meshes[player_id].rot_y += 0.01;

}

if obj_turn_right

{

static_meshes[player_id].rot_y -= 0.01;

}

if obj_turn_up

{

static_meshes[player_id].rot_x += 0.01;

}

if obj_turn_down

{

static_meshes[player_id].rot_x -= 0.01;

}

if cam_forward

{

camera.x -= 0.01 * camera.rot_y.sin();

camera.z -= 0.01 * camera.rot_y.cos();

}

if cam_backward

{

camera.x += 0.01 * camera.rot_y.sin();

camera.z += 0.01 * camera.rot_y.cos();

}

if cam_left

{

camera.x -= 0.01 * camera.rot_y.cos();

camera.z -= 0.01 * -camera.rot_y.sin();

}

if cam_right

{

camera.x += 0.01 * camera.rot_y.cos();

camera.z += 0.01 * -camera.rot_y.sin();

}

if cam_turn_left

{

camera.rot_y += 0.01;

}

if cam_turn_right

{

camera.rot_y -= 0.01;

}

if cam_turn_up

{

camera.rot_x += 0.01;

camera.rot_x = camera.rot_x.min(core::f32::consts::PI / 2.0);

}

if cam_turn_down

{

camera.rot_x -= 0.01;

camera.rot_x = camera.rot_x.max(-core::f32::consts::PI / 2.0);

}

// ...

Now it's time to create a shader accessible representation we can copy this data into!

Camera and Object GPU data

Now that our models are 3D, we need our transformations to be 3D as well. We already discussed how 4x4 matrices can hold 3D transformations, we wrote functions for a few basic transformations, and the conventional approach of representing transforms with model, view and projection matrices.

Now we will implement all of it: our object transforms will be stored in a 4x4 model matrix, and our camera will be stored in a 4x4 view and a 4x4 projection matrix.

First let's create the camera data containing a view and a projection matrix.

//

// Uniform data

//

#[repr(C, align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct CameraData

{

projection_matrix: [f32; 16],

view_matrix: [f32; 16]

}

// ...

Then a data structure for scene objects containing a model matrix instead of the previous 2D position and scale.

//

// Uniform data

//

// ...

#[repr(C, align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct ObjectData

{

model_matrix: [f32; 16]

}

// ...

The uniform buffer size will be calculated based on these data structures.

//

// Uniform data

//

// ...

let max_object_count = 64;

let frame_data_size = core::mem::size_of::<CameraData>() + max_object_count * core::mem::size_of::<ObjectData>();

// ...

Pay attention that we increased max_object_count as well.

Uniform upload

We need to extract the state of the current frame to the GPU side buffer of the current frame. We still get a pointer to the beginning of the uniform buffer memory, but this time instead of filling it with mostly hardcoded data, we will fill it with the transforms of the scene objects.

//

// Uniform upload

//

{

// Getting references

let camera_data;

let object_data_array;

unsafe

{

let per_frame_region_begin = uniform_buffer_ptr.offset(

(current_frame_index * padded_frame_data_size) as isize

);

let camera_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<CameraData> = core::mem::transmute(per_frame_region_begin);

camera_data = &mut *camera_data_ptr;

let object_data_offset = core::mem::size_of::<CameraData>() as isize;

let object_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<ObjectData> = core::mem::transmute(

per_frame_region_begin.offset(object_data_offset)

);

object_data_array = core::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(

object_data_ptr,

max_object_count

);

}

// Filling them with data

let field_of_view_angle = core::f32::consts::PI / 3.0;

let aspect_ratio = width as f32 / height as f32;

let projection_matrix = shitty_perspective(

field_of_view_angle,

aspect_ratio

);

*camera_data = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

CameraData {

projection_matrix: mat_mlt(

&projection_matrix,

&scale(1.0, -1.0, -1.0)

),

view_matrix: mat_mlt(

&rotate_x(-camera.rot_x),

&mat_mlt(

&rotate_y(-camera.rot_y),

&translate(

-camera.x,

-camera.y,

-camera.z

)

)

)

}

);

for (i, static_mesh) in static_meshes.iter().enumerate()

{

object_data_array[i] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

ObjectData {

model_matrix: mat_mlt(

&translate(

static_mesh.x,

static_mesh.y,

static_mesh.z

),

&mat_mlt(

&rotate_x(static_mesh.rot_x),

&mat_mlt(

&rotate_y(static_mesh.rot_y),

&scale(

static_mesh.scale,

static_mesh.scale,

static_mesh.scale

)

)

)

)

}

);

}

}

// ...

First off the uniform buffer upload will be wrapped in a block to make sure that the variables holding the uniform buffer's per frame ranges go out of scope after we finished uploading.

We get pointers just as we did originally.

The first part that's really different is the camera data upload.

We construct the projection matrix, which will project the 3D objects onto the 2D screen and corrects with the field of view and aspect ratio. Pay attention that we also multiply the projection matrix with a matrix that flips the Y and Z axes! We flip the Y coordinate because in normalized device coordinates the positive Y axis points downwards, and among humans it's more conventional to have the positive Y axis point upwards. Flipping the Z coordinate is just a personal preference of mine. When you are flipping axes, pay attention that you are conscious about whether the resulting coordinate system is left or right handed, etc. It can also affect backface culling if you studied and enabled it.

Then the view matrix is constructed by basically moving the origin into the camera's position and performing the inverse rotations of the camera's transformation.

Then we finally upload the model matrix of every scene object according to their position, rotation and scale.

Now that the uniform data is uploaded, let's issue draw calls for every static mesh!

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

// ...

// ...

// Setting per frame descriptor array index

let ubo_desc_index: u32 = current_frame_index as u32;

// vkCmdPushConstants

for (i, static_mesh) in static_meshes.iter().enumerate()

{

// Per obj array index

let object_index = i as u32;

vkCmdPushConstants(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

pipeline_layout,

VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

0,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

&object_index as *const u32 as *const core::ffi::c_void

);

// Setting texture descriptor array index

vkCmdPushConstants(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

pipeline_layout,

VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

2 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

&static_mesh.texture_index as *const u32 as *const core::ffi::c_void

);

vkCmdDrawIndexed(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

models[static_mesh.model_index].index_count,

1,

models[static_mesh.model_index].first_index,

models[static_mesh.model_index].vertex_offset,

0

);

}

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

// ...

We iterate over every scene object, upload its transform and texture index into push constants analogously to what we did before, then we read the index count, first index and vertex offset of their model, and issue a draw call.

Vertex shader

Now it's time to adjust our uniform data format! After that we need to perform our P*V*M multiplication and transform the position.

#version 460

struct CameraData

{

mat4 projection_matrix;

mat4 view_matrix;

};

struct ObjectData

{

mat4 model_matrix;

};

const uint MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 8;

const uint MAX_OBJECT_COUNT = 64;

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 0) uniform UniformData {

CameraData cam_data;

ObjectData obj_data[MAX_OBJECT_COUNT];

} uniform_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

layout(push_constant) uniform ResourceIndices {

uint obj_index;

uint ubo_desc_index;

} resource_indices;

layout(location = 0) in vec3 position;

layout(location = 1) in vec2 tex_coord;

layout(location = 0) out vec2 frag_tex_coord;

void main()

{

uint ubo_desc_index = resource_indices.ubo_desc_index;

uint obj_index = resource_indices.obj_index;

mat4 model_matrix = uniform_data[ubo_desc_index].obj_data[obj_index].model_matrix;

vec4 world_position = model_matrix * vec4(position, 1.0);

mat4 view_matrix = uniform_data[ubo_desc_index].cam_data.view_matrix;

vec4 view_position = view_matrix * world_position;

frag_tex_coord = tex_coord;

mat4 projection_matrix = uniform_data[ubo_desc_index].cam_data.projection_matrix;

gl_Position = projection_matrix * view_position;

}

The first few lines represent our scene data. The structs CameraData and ObjectData

are adapted to fit the rust counterparts: the latter now contains a model matrix, and the former a view and

a projection matrix. Notice that just like vec4, mat4 is a built in type in GLSL.

The way we laid out our matrix column by column in memory, it will be correctly interpreted in shader. We also

adapted MAX_OBJECT_COUNT to be 64 to match the new parameters present in rust.

The position attribute is now a vec3, passing the Z coordinate as well. The push

constants and the rest of the in and out variables are unchanged.

Now let's talk about the main function where many interesting things happen! Using the obj_index

push constant we fetch the model matrix. Then we extend the position attribute to be a 4D vector, representing

it with homogeneous coordinates, setting the z coordinate to 1.0. This way we can multiply it with

the model matrix from the left. The * operator between a 4x4 matrix and a 4D vector is defined to

be the same matrix multiplication we already covered. This transforms position from object space to

world space, and the result is stored in the variable world_position.

Then we fetch the view matrix, and multiply the world space coordinates with it from the left, transforming it

from world space to view space. This will be stored in view_position.

The final important change is taking the world space coordinates and multiplying it with the projection matrix.

This will project the vector onto the clipping plane, and scale the x and y coordinates based on the field of

view and aspect ratio. This can finally be stored in gl_Position and the triangles can be

rasterized.

I saved this file as 05_3d.vert into the shader_src/vertex_shaders directory.

Let's compile it...

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/05_3d.vert.spv ./shader_src/vertex_shaders/05_3d.vert

...and load it!

//

// Shader modules

//

// Vertex shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/05_3d.vert.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

// ...

...and that's it! ...or is it?

Noticing a problem

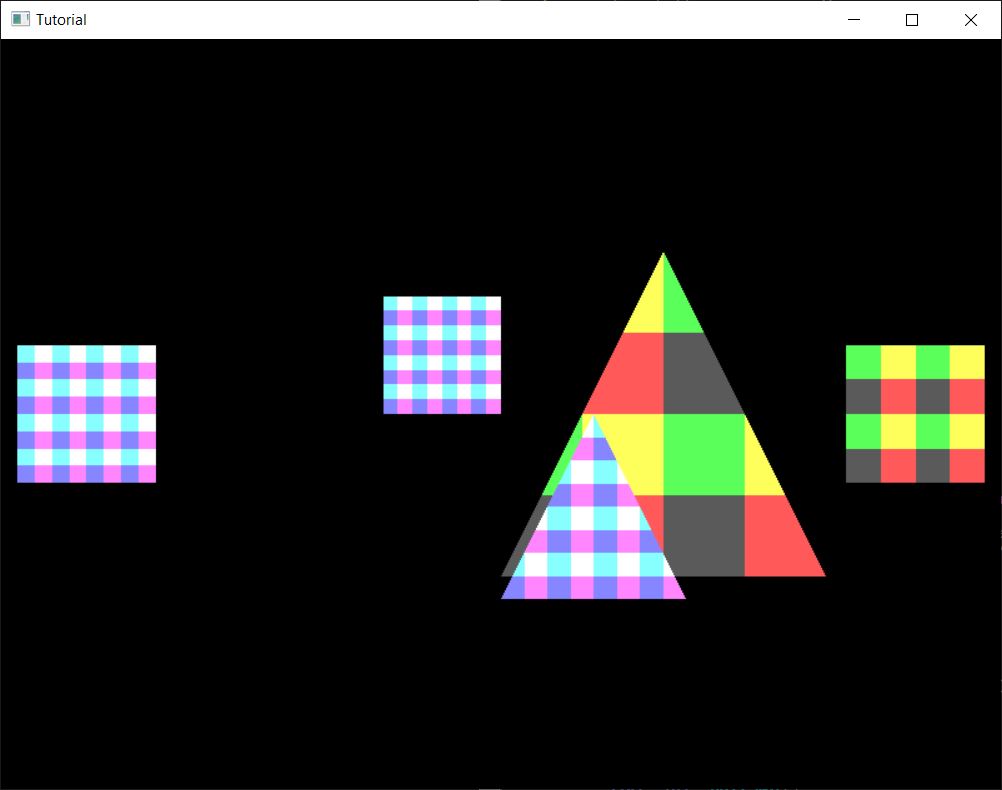

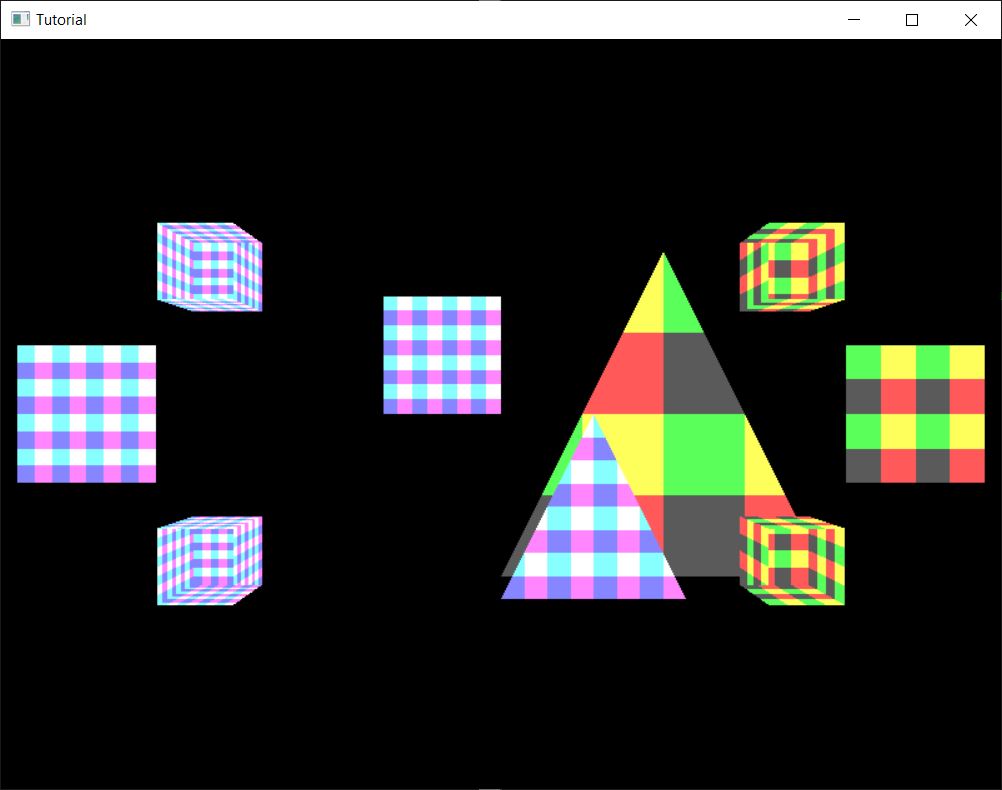

Well... if we run our program, it kinda works... Distant things are smaller, closer things are larger, but something is off.

Let's move our player character around a bit...

It seems that no matter how far our player character is, closer things do not cover it, and no matter how close it is, it does not cover distant things. The problem is, scene objects get drawn in draw call order, and scene objects drawn later cover things, even if they are further from the camera.

Before we even start coming up with a solution, let's extend our application a bit!

Adding a cube

If we add a 3D model that's thick, we notice that this problem is worse than it seems. Let's add a cube model!

Here is the data for a cube!

//

// Vertex and Index data

//

// ...

let cube_vertices: Vec<f32> = vec![

// Pos Z

// Vertex 0

-0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

-0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

// Neg Z

// Vertex 0

-0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

-0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

// Pos X

// Vertex 0

0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

// Neg X

// Vertex 0

-0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

-0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

-0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

-0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

// Pos Y

// Vertex 0

-0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

-0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

// Neg Y

// Vertex 0

-0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

-0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

];

let cube_indices: Vec<u32> = vec![

// Pos Z

0, 2, 1, 0, 3, 2,

// Neg Z

4, 5, 6, 4, 6, 7,

// Pos X

8, 10, 9, 8, 11, 10,

// Neg X

12, 13, 14, 12, 14, 15,

// Pos Y

16, 17, 18, 16, 18, 19,

// Neg Y

20, 22, 21, 20, 23, 22

];

// ...

...and since the data definitions are getting huge, we may want to extract these into functions...

//

// Example models

//

fn create_tri_and_quad_vertices() -> Vec<f32>

{

vec![

// ...

]

}

fn create_tri_and_quad_indices() -> Vec<u32>

{

vec![

// ...

]

}

fn create_cube_vertices() -> Vec<f32>

{

vec![

// ...

]

}

fn create_cube_indices() -> Vec<u32>

{

vec![

// ...

]

}

...and call them like this.

//

// Vertex and Index data

//

// I renamed vertices to tri_and_quad_vertices, and indices to tri_and_quad_indices.

let tri_and_quad_vertices = create_tri_and_quad_vertices();

let tri_and_quad_indices = create_tri_and_quad_indices();

let cube_vertices = create_cube_vertices();

let cube_indices = create_cube_indices();

// ...

This is what you will see in the samples. Since now we have two arrays of floats and integers, let's adjust the vertex and index buffer size!

//

// Vertex and Index data

//

// Vertex and Index buffer size

let tri_and_quad_vertex_data_size = tri_and_quad_vertices.len() * core::mem::size_of::<f32>();

let tri_and_quad_index_data_size = tri_and_quad_indices.len() * core::mem::size_of::<u32>();

let cube_vertex_data_size = cube_vertices.len() * core::mem::size_of::<f32>();

let cube_index_data_size = cube_indices.len() * core::mem::size_of::<u32>();

let vertex_data_size = tri_and_quad_vertex_data_size + cube_vertex_data_size;

let index_data_size = tri_and_quad_index_data_size + cube_index_data_size;

// ...

Now let's upload it to the staging buffer! The layout of the vertex and index data is slightly different, so we need to adjust the upload code. We will upload every vertex data to a contiguous memory region, and every index data right next to it into another contiguous region.

//

// Uploading to Staging buffer

//

let vertex_data_offset = 0;

let index_data_offset = vertex_data_size as u64;

unsafe

{

let mut data = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = vkMapMemory(

device,

staging_buffer_memory,

0,

staging_buffer_size as VkDeviceSize,

0,

&mut data

);

// ...

//

// Copy vertex and index data to staging buffer

//

// Triangle and quad vertex data

let vertex_data_offset = vertex_data_offset as isize;

let vertex_data_void = data.offset(vertex_data_offset);

let vertex_data_typed: *mut f32 = core::mem::transmute(vertex_data_void);

core::ptr::copy_nonoverlapping::<f32>(

tri_and_quad_vertices.as_ptr(),

vertex_data_typed,

tri_and_quad_vertices.len()

);

// Cube vertex data

let vertex_data_offset = vertex_data_offset + tri_and_quad_vertex_data_size as isize;

let vertex_data_void = data.offset(vertex_data_offset);

let vertex_data_typed: *mut f32 = core::mem::transmute(vertex_data_void);

core::ptr::copy_nonoverlapping::<f32>(

cube_vertices.as_ptr(),

vertex_data_typed,

cube_vertices.len()

);

// Triangle and quad index data

let index_data_offset = index_data_offset as isize;

let index_data_void = data.offset(index_data_offset);

let index_data_typed: *mut u32 = core::mem::transmute(index_data_void);

core::ptr::copy_nonoverlapping::<u32>(

tri_and_quad_indices.as_ptr(),

index_data_typed,

tri_and_quad_indices.len()

);

// Cube index data

let index_data_offset = index_data_offset + tri_and_quad_index_data_size as isize;

let index_data_void = data.offset(index_data_offset);

let index_data_typed: *mut u32 = core::mem::transmute(index_data_void);

core::ptr::copy_nonoverlapping::<u32>(

cube_indices.as_ptr(),

index_data_typed,

cube_indices.len()

);

// ...

}

// ...

Now we just need to add the draw arguments of the cube mesh to the list of models.

//

// Model and Texture ID-s

//

// Models

// ...

const PER_VERTEX_DATA_SIZE: usize = 5;

// ...

let cube_index = 2;

let models = [

// ...

// Cube

Model {

index_count: cube_indices.len() as u32,

first_index: tri_and_quad_indices.len() as u32,

vertex_offset: (tri_and_quad_vertices.len() / PER_VERTEX_DATA_SIZE) as i32

}

];

// ...

Now let's add the cube scene elements!

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

// Cubes added later

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 1.0,

y: 0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 1.0,

y: -0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -1.0,

y: 0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -1.0,

y: -0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

// ...

Now since our code uploads and draws every scene object, we don't need to do anything else, just compile and run the application, and...

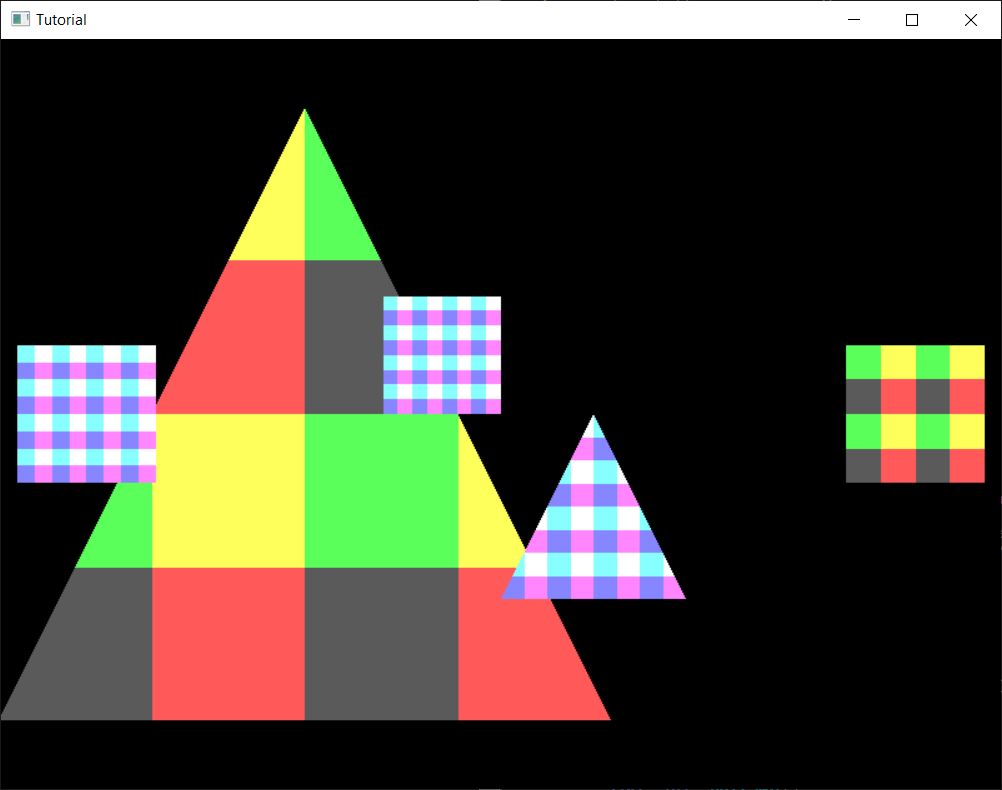

WHAT THE HELL? We can see the cubes, but they look really wrong. Move around the camera and see for yourself!

When you only moved triangles, it seemed only scene objects fail to cover each other, but this is way worse. Even the triangles within a single model are drawn in an order that depends on the triangle order in the index buffer. On cubes depending on the camera position and the index buffer content backfaces will be drawn on top of front faces, making it look horrible.

Now we understand why shitty_perspective was shitty, and why zeroing the z coordinate causes problems.

If we had a sane z coordinate, we could decide which triangle should be visible for a given pixel, and this is what

depth buffer will be used for in the next tutorial.

Wrapping up

In this chapter we learned how to represent a 3D scene with 3D models, and how to project them onto the 2D screen to give the illusion of 3D. We also learned a bit of linear algebra that will help you dealing with both 2D and 3D graphics for the rest of your life.

However we have also learned that simply projecting 3D vertices the right way does not result in correct 3D rendering. Backfaces may cover front faces and models far away can cover models closer, which is wrong. In the next chapter we will take the final step to address this issue and finally draw our 3D world correctly.

The sample code for this tutorial can be found here.

The tutorial continues here.