Uniform buffer

In the previous chapter we made modifications to our application that helps take advantage of the memory heaps of a dedicated GPU.

We also briefly discussed a whole set of new problems to solve, such as allocating resources to the right heap, handling memory overcommitment and resource residency, and so on. We did not solve them, but at least you know they exist and have the links of some learning material.

Regardless of the importance of identifying and solving these problems, our addition did not result in a fancy new feature: it still draws a triangle and a quad. This time, we explore how to draw the same model many times, and will introduce ourselves to a myriad of new Vulkan objects.

This tutorial is in open beta. There may be bugs in the code and misinformation and inaccuracies in the text. If you find any, feel free to open a ticket on the repo of the code samples.

Drawing multiple objects

In our vertex and index buffer chapter we uploaded some very simple geometry into vertex and index buffers and built up a concept of a model. We hadded an additional model, showing an API usage for rendering multiple models, and rendered it to the screen. The problem was that the vertices of every model was fixed. A normal scene will be more complicated with the same model being drawn in different positions, maybe scaled, rotated, etc. and the only way to do that with vertex and index buffers, is to write new vertex positions for every scene element. This may be fine, or even preferable for small models such as triangles and quads, but it will be slow for large models. So we need to solve the problem of rendering scene objects using the same vertices and indices many times with different transforms.

Uniform variables

Previously we have only seen variables containing vertex attributes, variables representing fragment shader

outputs, and some built-in variables, such as gl_VertexIndex. What they had in common is how they

were read from and written to memory from shaders was only controllable by us indirectly. We set up vertex

attributes and vertex buffer bindings, index buffers, attachments, and did not read them by issuing memory

read operations.

Uniform variables hold globally accessable constant data. They can be backed by memory or be set from command buffers, depending on the kind of uniform variable. Using uniform variables we can define per draw call transform data and identifiers, and can be used to transform vertices.

Using them we can reuse the same model residing in our vertex and index buffer for many scene objects, upload their transform data such as translation, rotation and scaling, and calculate different final vertex positions per scene object in the vertex shader.

Uniform variables are variables defined using slightly different syntax than in variables holding

per vertex data. Examples can be seen in the following two code snippets.

If you define them like below, they will be backed by buffers.

#version 460

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 0) uniform UniformData

{

vec4 data;

} uniform_data;

layout(location = 0) in vec2 position;

void main()

{

vec2 obj_pos = uniform_data.data.xy;

vec2 vertex_pos = obj_pos + position;

gl_Position = vec4(vertex_pos, 0.0, 1.0);

}

The layout(std140, set=0, binding = 0) part defines their memory layout, and in a way which

buffer it is coming from. (You will see a proper explanation later.) Then the uniform keyword

indicates that the variable is a uniform, then come the data type and the variable name.

In the main function the uniform_data.data.xy part accesses this data and stores

it in the variable obj_pos. Then it gets added to the vertex position read from the vertex buffer,

effectively translating it.

They don't have to come from memory though. A limited amount of data can be set from the command buffers. These are called push constants and they can be suitable for tiny data. An example can be seen below.

#version 460

layout(push_constant) uniform UniformData

{

vec4 data;

} uniform_data;

layout(location = 0) in vec2 position;

void main()

{

vec2 obj_pos = uniform_data.data.xy;

vec2 vertex_pos = obj_pos + position;

gl_Position = vec4(vertex_pos, 0.0, 1.0);

}

The code is very similar to the previous one, but the layout(push_constant) makes it a push

constant and it will be settable from the command buffer.

There are some blind spots, such as what is a set and binding really is, and what

is exactly a push constant. We will learn about them as we go over their Vulkan counterparts.

Scene representation

In this chapter we will define a scene representation that can be uploaded into a buffer and made accessible to the vertex shader. It will be a camera data, so we can move the camera, and an array of object transforms containing 2D position and scale.

We will define a push constant as well to hold the index of the object rendered by the current draw call. It will be set before the draw call and used to index into the object transform array.

We are going to have three objects for now. How they can be extended considering hardware limitations will be evident.

Preparing vertex data

Our original vertex buffer content contained the model's final position on the image. Now that we want to reuse the same vertex data for many scene objects, and there is no single "final position", we move the vertices to a common frame of reference, which will be the object space.

Object space is the coordinate system where the model is defined.

For every scene element using a specific model we will move, rotate, scale, etc. the model from object space to the scene element's destination.

Let's adjust our vertex data so the coordinates will be defined in object space.

//

// Vertex and Index data

//

let vertices: Vec<f32> = vec![

// Triangle

// Vertex 0

-1.0, -1.0,

// Vertex 1

1.0, -1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.0, 1.0,

// Quad

// Vertex 0

-1.0, -1.0,

// Vertex 1

1.0, -1.0,

// Vertex 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

-1.0, 1.0

];

// ...

Now that our model is made reusable, it's time to understand some conventions for coordinate systems in computer graphics and define our data structure for the scene.

Defining scene data structure

In order to define the transformation of a scene object, we need a frame of reference for the scene.

World space is the coordinate system where the scene is defined.

The scene elements' transformation is defined within world space. Conventionally the origin of world space is the center of the scene and one of the axes tends to be the "up" or "down" direction.

Then we usually want a camera that we can move around in scene space and the part of the scene the camera "sees" will be rendered to the image. This is done by giving it a transformation defined in world space, and when we want to render, we move the visible scene elements into the coordinate system of the camera.

View space is the coordinate system local to the camera. It's origin is in the camera's position and its axes are aligned with the "up", "down", "left", "right" and "forward" directions of the camera.

Eventually the vertices need to end up in normalized device coordinates so they can be rasterized, so we need to transform from view space to normalized device coordinates.

Knowing these conventions we can finally define data structures for our camera and object transforms. Our scene will be a very basic 2D scene.

Our object transforms will be the translation from the scene origin to the scene object's position, and a uniform scaling to can resize our object. To construct these we will need the x and y coordinates and the scaling factor.

Our camera transform will be the translation from the scene origin to the camera's position. For this we need the camera's x and y coordinates. We will also scale the scene objects so resizing the window won't distort the models. For this we will need the aspect ratio and a scaling along one of the axes. For the sake of simplicity I will add aspect ratio to the camera data.

Our scene data structure will support a single camera and three scene objects.

Taking inspiration from the AMD Vulkan fast paths presentation, which encourages placing data common for every draw call to the beginning of the buffer, and then accessing per draw data with push constants, I will put the camera (what is common for every draw call) to the beginning of the buffer, and the scene object transforms in an array after it. In the final shader I will index into it with a push constant, which I will set before every draw call.

We define our structs in GLSL and rust below.

GLSL:

struct CameraData

{

vec2 position;

float aspect_ratio;

};

struct ObjectData

{

vec2 position;

float scale;

};

const uint MAX_OBJECT_COUNT = 3;

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 0) uniform UniformData {

CameraData cam_data;

ObjectData obj_data[MAX_OBJECT_COUNT];

} uniform_data;

Rust:

//

// Uniform data

//

#[repr(C, align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct CameraData

{

x: f32,

y: f32,

aspect_ratio: f32,

std140_padding_0: f32,

}

#[repr(C, align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct ObjectData

{

x: f32,

y: f32,

scale: f32,

std140_padding_0: f32

}

let max_object_count = 3;

let frame_data_size = core::mem::size_of::<CameraData>() + max_object_count * core::mem::size_of::<ObjectData>();

let uniform_buffer_size = frame_data_size;

// ...

We need to add repr(C, align(16)) to our structs to make sure they get a well defined memory layout.

We will need three floats. For ObjectData, which is our scene element, it's x,

y and scale. For our CameraData it's x,

y and aspect_ratio. The tightly packed x: f32 and y: f32

variables match the memory layout of the vec2 position in both structs.

What is the fourth one, std140_padding_0? For this we

need to talk about the memory layout of GLSL types.

In GLSL by default if we load uniform data from buffers, we need to arrange it in memory following the

std140 layout rules. This is defined in the

OpenGL spec in section 7.6.2.1 and

7.6.2.2. The important thing is that the alignment of structs are rounded up to the multiple of the size of a

vec4, which is 16 bytes. I add these std140_padding_0 variables not because it's

necessary (The align(16) handles that), but to make sure you see where they are. In some cases it

may be necessary. Read about the std140 layout rules in GLSL and repr(C) in rust as you create more complicated

data structures!

Uniform buffers

So far we have seen buffers contain vertex and index data, but depending on their usage flags, they can contain other kinds of data as well. If we want a uniform variable to come from memory, it needs to be backed by a special kind of buffer.

In Vulkan a uniform buffer is a buffer that can back a uniform variable.

Now we create one very similarly to how we created the vertex, index and staging buffer.

Buffer creation

Uniform buffers are created the same way we did before, just we need new usage flags.

Let's determine the memory property flags! We want to write it from the CPU, so I choose

VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_VISIBLE_BIT | VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_COHERENT_BIT.

//

// Uniform data

//

// ...

let uniform_buf_mem_props = (VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_VISIBLE_BIT | VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_COHERENT_BIT) as VkMemoryPropertyFlags;

// ...

Now we create the buffer, allocate memory and bind it.

//

// Uniform buffers

//

// Create buffer

let uniform_buffer_create_info = VkBufferCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_BUFFER_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

size: uniform_buffer_size as VkDeviceSize,

usage: VK_BUFFER_USAGE_UNIFORM_BUFFER_BIT as VkBufferUsageFlags,

sharingMode: VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE,

queueFamilyIndexCount: 0,

pQueueFamilyIndices: core::ptr::null()

};

println!("Creating uniform buffer.");

let mut uniform_buffer = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateBuffer(

device,

&uniform_buffer_create_info,

core::ptr::null(),

&mut uniform_buffer

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create uniform buffer. Error: {}.", result);

}

// Create memory

let mut mem_requirements = VkMemoryRequirements::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetBufferMemoryRequirements(

device,

uniform_buffer,

&mut mem_requirements

);

}

let mut chosen_memory_type = phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount;

for i in 0..phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

if mem_requirements.memoryTypeBits & (1 << i) != 0 &&

(phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypes[i as usize].propertyFlags & uniform_buf_mem_props) == uniform_buf_mem_props

{

chosen_memory_type = i;

break;

}

}

if chosen_memory_type == phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

panic!("Could not find memory type.");

}

let uniform_buffer_alloc_info = VkMemoryAllocateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_MEMORY_ALLOCATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

allocationSize: mem_requirements.size,

memoryTypeIndex: chosen_memory_type

};

println!("Uniform buffer size: {}", mem_requirements.size);

println!("Uniform buffer align: {}", mem_requirements.alignment);

println!("Allocating uniform buffer memory.");

let mut uniform_buffer_memory = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkAllocateMemory(

device,

&uniform_buffer_alloc_info,

core::ptr::null(),

&mut uniform_buffer_memory

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Could not allocate memory. Error: {}.", result);

}

// Bind buffer to memory

println!("Binding uniform buffer memory.");

let result = unsafe

{

vkBindBufferMemory(

device,

uniform_buffer,

uniform_buffer_memory,

0

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to bind memory to uniform buffer. Error: {}.", result);

}

// ...

For uniform buffers the usage flag is VK_BUFFER_USAGE_UNIFORM_BUFFER_BIT.

After creation we do one thing differently: we map it once, and leave it like that until the end of the program. This will be a persistent mapped buffer.

//

// Uniform buffers

//

// ...

// Map memory persistently

let mut uniform_buffer_ptr = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkMapMemory(

device,

uniform_buffer_memory,

0,

uniform_buffer_size as VkDeviceSize,

0,

&mut uniform_buffer_ptr

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to map memory. Error: {}.", result);

}

// ...

Then we do the cleanup at the end of the program. Notice that before destruction we unmap the memory!

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting uniform buffer device memory");

unsafe

{

vkUnmapMemory(

device,

uniform_buffer_memory

);

vkFreeMemory(

device,

uniform_buffer_memory,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

println!("Deleting uniform buffer");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyBuffer(

device,

uniform_buffer,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

Ok, we have our uniform buffer and memory holding its data. First we take baby steps and only upload the scene once before the main loop. Later in this chapter we will make the camera and one of the scene objects movable, but that comes later.

Let's get references to the memory of the camera and the array of object transforms and upload some arbitrary data to it!

//

// Uniform upload

//

// Getting references

let camera_data;

let object_data_array;

unsafe

{

let camera_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<CameraData> = core::mem::transmute(

uniform_buffer_ptr

);

camera_data = &mut *camera_data_ptr;

let object_data_offset = core::mem::size_of::<CameraData>() as isize;

let object_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<ObjectData> = core::mem::transmute(

uniform_buffer_ptr.offset(object_data_offset)

);

object_data_array = core::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(

object_data_ptr,

max_object_count

);

}

*camera_data = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

CameraData {

x: 0.0,

y: -0.25,

aspect_ratio: width as f32 / height as f32,

std140_padding_0: 0.0

}

);

object_data_array[0] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

ObjectData {

x: 0.25,

y: 0.25,

scale: 0.25,

std140_padding_0: 0.0

}

);

object_data_array[1] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

ObjectData {

x: 0.25,

y: -0.25,

scale: 0.25,

std140_padding_0: 0.0

}

);

object_data_array[2] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

ObjectData {

x: -0.25,

y: 0.25,

scale: 0.25,

std140_padding_0: 0.0

}

);

// ...

One thing to pay very close attention is that the camera_data and object_data_array

are references, but their lifetime is not tied to a variable. They easily outlive the pointers I dereferenced.

In a real world application you should bind their lifetime to some variable, and just for the sake of being

pedantic, make sure the references go out of scope by the time the GPU processes the data.

The other thing is that the memory behind camera_data and object_data_array may not

be initialized, so I decided to use core::mem::MaybeUninit.

Descriptors and descriptor sets

In Vulkan uniform buffers are not referenced directly. Instead we need to create something called a descriptor.

Descriptors are opaque data structures representing GPU resources such as buffers and images.

A descriptor set is a collection of descriptors that we can bind at once during rendering. It has multiple bindings, each containing an array of descriptors of the same resource type.

Descriptor set layout

In Vulkan before you could create descriptor sets you need to define their schema.

Descriptor set layouts are vulkan objects that define the schema of descriptor sets. They define bindings, their descriptor type and array size.

For now we create a very simple descriptor layout: a singe binding which holds a single descriptor.

//

// Descriptor set layout

//

let max_ubo_descriptor_count = 1;

let layout_bindings = [

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding {

binding: 0,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

descriptorCount: max_ubo_descriptor_count,

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

pImmutableSamplers: core::ptr::null()

}

];

let descriptor_set_layout_create_info = VkDescriptorSetLayoutCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_DESCRIPTOR_SET_LAYOUT_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

bindingCount: layout_bindings.len() as u32,

pBindings: layout_bindings.as_ptr()

};

println!("Creating descriptor set layout.");

let mut descriptor_set_layout = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateDescriptorSetLayout(

device,

&descriptor_set_layout_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut descriptor_set_layout

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create descriptor set layout. Error: {}.", result);

}

// ...

The most important parts of VkDescriptorSetLayoutCreateInfo are bindingCount and

pBindings, which refer to an array of bindings. We set everything else to zero.

Our binding array will contain a single binding that refers to our uniform buffer. The

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding struct has a binding field, which is an integer

identifier of the binding, a descriptorType defining what kind of resource it refers to,

descriptorCount defining the number of descriptors in this binding, the stageFlags

defining the shader stage this binding is available to, and pImmutableSamplers, which we won't

get into and set to null pointer.

We need to destroy the descriptor set layout at the end of the program.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting descriptor set layout");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyDescriptorSetLayout(

device,

descriptor_set_layout,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

Now that we have the schema for our descriptor set, let's create it. Descriptor sets are allocated from pools, so let's create one!

Descriptor pool

A descriptor pool is a non threadsafe pool of descriptors from which you can allocate descriptor sets.

//

// Descriptor pool & descriptor set

//

let pool_sizes = [

VkDescriptorPoolSize {

type_: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

descriptorCount: max_ubo_descriptor_count

}

];

let descriptor_pool_create_info = VkDescriptorPoolCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_DESCRIPTOR_POOL_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

maxSets: 1,

poolSizeCount: pool_sizes.len() as u32,

pPoolSizes: pool_sizes.as_ptr()

};

println!("Creating descriptor pool.");

let mut descriptor_pool = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateDescriptorPool(

device,

&descriptor_pool_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut descriptor_pool

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create descriptor pool. Error: {}", result);

}

// ...

The three important fields of VkDescriptorPoolCreateInfo are the maxSets, which

defines how many descriptor sets can be allocated from it, and pPoolSizes and

poolSizeCount pointing to an array of VkDescriptorPoolSize structs. These define

how many descriptors will be allocated from the pool.

We only want uniform buffers, so we have one element in the VkDescriptorPoolSize array. Its

type_ will be VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER, and the descriptorCount

will be set to the variable max_ubo_descriptor_count. We used this when we filled the binding

data of the descriptor set layout, so they will match.

(Notice the underscore at the end of type_! It is a rust specific necessity and comes from bindgen.

In the spec it's simply type. It will still work, but in case you need to read the spec, don't let

it confuse you!)

When descriptor pools are destroyed, descriptor sets allocated from them are freed as well.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting descriptor pool.");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyDescriptorPool(

device,

descriptor_pool,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

Descriptor sets

Descriptor sets are specific allocations of descriptors arranged in the way a descriptor set layout defines it. This is what we can use during command recording.

Let's allocate our descriptor set from the previously defined descriptor pool!

//

// Descriptor pool & descriptor set

//

// ...

// Allocating descriptor set

let descriptor_set_layouts = [

descriptor_set_layout

];

let descriptor_set_alloc_info = VkDescriptorSetAllocateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_DESCRIPTOR_SET_ALLOCATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

descriptorPool: descriptor_pool,

descriptorSetCount: descriptor_set_layouts.len() as u32,

pSetLayouts: descriptor_set_layouts.as_ptr()

};

println!("Allocating descriptor set.");

let mut descriptor_set = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkAllocateDescriptorSets(

device,

&descriptor_set_alloc_info,

&mut descriptor_set

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to allocate descriptor set. Error: {}", result);

}

// ...

The parameters of the allocation is in the VkDescriptorSetAllocateInfo struct, where

descriptorPool contains the descriptor pool to allocate from, and the pSetLayouts

and descriptorSetCount combo refers to an array of descriptor set layouts. These descriptor set

layouts will determine how many bindings there are, and the count and type of descriptors in these bindings.

That's enough info to successfully allocate.

Now we need it to refer to our uniform buffer. We do this by writing the right kind of data into the descriptors.

//

// Descriptor pool & descriptor set

//

// ...

// Writing descriptor set

let mut ubo_descriptor_writes = Vec::with_capacity(max_ubo_descriptor_count as usize);

ubo_descriptor_writes.push(

VkDescriptorBufferInfo {

buffer: uniform_buffer,

offset: 0,

range: frame_data_size as VkDeviceSize

}

);

let descriptor_set_writes = [

VkWriteDescriptorSet {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_WRITE_DESCRIPTOR_SET,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

dstSet: descriptor_set,

dstBinding: 0,

dstArrayElement: 0,

descriptorCount: ubo_descriptor_writes.len() as u32,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

pImageInfo: core::ptr::null(),

pBufferInfo: ubo_descriptor_writes.as_ptr(),

pTexelBufferView: core::ptr::null()

}

];

println!("Updating descriptor sets.");

unsafe

{

vkUpdateDescriptorSets(

device,

descriptor_set_writes.len() as u32,

descriptor_set_writes.as_ptr(),

0,

core::ptr::null()

);

}

// ...

Now take some time to digest what we see here and the explanation!

The function vkUpdateDescriptorSets expects an array of VkWriteDescriptorSet structs.

The VkWriteDescriptorSet struct is enormous and we only get into details about some of its fields.

The dstSet identifies the descriptor set to write to, which is the newly allocated

descriptor_set, dstBinding identifies the binding, which will be 0,

descriptorType identifies the descriptor type of the binding, which is

VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER, and then we identify the subset of the descriptors to write

and their new contents.

dstArrayElement specifies the first descriptor to be overwritten. Since we overwrite all of them,

the first array index will be 0. Then descriptorCount and the array pointer matching

descriptorType, in our case pBufferInfo, defines the amount of descriptors to write

and their new contents.

Our array will be ubo_descriptor_writes, which will be a vec. We add a hint to the constructor to

reserve memory. Then we push the VkDescriptorBufferInfo of our single descriptor. The buffer

will be uniform_buffer, the offset will be 0, since the beginning of

the scene data is at the beginning of the buffer, and the range will be

frame_data_size, since the scene data will take that much memory, and all of it needs to be

accessible from the shader.

Ranges bound by a UBO descriptor cannot exceed maxUniformBufferRange. The buffer can be bigger,

but only a small portion will be accessible through a single uniform buffer descriptor. The minimum

maxUniformBufferRange value will be 16384, which we will definitely not exceed.

NVidia GPUs tend to support at least 65536 bytes, and AMD GCN cards and newer tend to allow

4294967295. If you have data that exceed 64 kilobytes, you can partition it into

multiple regions for NVidia GPUs. Later in the tutorial you'll see how more buffer ranges can all be

accessible.

Id Software used many uniform buffer partitions in Doom 2016 while kept a single large region (actually used a different kind of buffer) for AMD. Their presentation can be found here.

Pipeline setup

Pipeline layout

Now we can talk about pipeline layouts. In the hardcoded triangle chapter we did not get into details, because we could not get our hands ditry and that's the best way to understand things, but this has changed.

The pipeline layout schematically lays out what kind of GPU resources (linear buffers and textures) and push constants will the pipeline use.

Now we have uniform buffers and push constants. Let's fill the pipeline layout with it!

The descriptor sets must be supplied as an array of descriptor set layouts.

//

// Pipeline layout

//

let descriptor_set_layouts = [

descriptor_set_layout

];

// ...

The push constants must be supplied as an array of ranges.

//

// Pipeline layout

//

// Object ID

let push_constant_size = 1 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32;

let push_constant_ranges = [

VkPushConstantRange {

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

offset: 0,

size: push_constant_size,

}

];

// ...

The struct is VkPushConstantRange. The range needs to hold a single 32 bit integer, so that will

be the size, the offset will be zero, and stageFlags determine what

pipeline stages will access this data, which will be VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT.

We supply these arrays to the create info, and we already have creation and cleanup code from the previous tutorials, so we are done.

//

// Pipeline layout

//

let pipeline_layout_create_info = VkPipelineLayoutCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_LAYOUT_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

setLayoutCount: descriptor_set_layouts.len() as u32,

pSetLayouts: descriptor_set_layouts.as_ptr(),

pushConstantRangeCount: push_constant_ranges.len() as u32,

pPushConstantRanges: push_constant_ranges.as_ptr()

};

// ...

Now recalling how the uniform variable in the shader code used layout(std140, set=0, binding=0),

we know what set and binding really is. During rendering the pipeline layout allows

many potential descriptor sets, and set identifies which one contains this uniform variable's

descriptor. Each descriptor set may have many bindings for buffers with different memory layout, images,

and so on, and binding identifies which one backs this variable.

Command recording

It's time to use the descriptor set during rendering.

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

// ...

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

Binding descriptor set

Once we have a descriptor set, we need to bind it during rendering just like we did the vertex and index buffers. I'll bind it right before we bind the vertex and index buffers.

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

// ...

let descriptor_sets = [

descriptor_set

];

vkCmdBindDescriptorSets(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

VK_PIPELINE_BIND_POINT_GRAPHICS,

pipeline_layout,

0,

descriptor_sets.len() as u32,

descriptor_sets.as_ptr(),

0,

core::ptr::null()

);

// Binding the vertex buffer comes here.

// ...

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

Encoding push constant

Then for every object we supply a per draw index before draw call.

We can even uncomment our first triangle that would have been covered by the indexed triangle.

Let this be our first object with object_index = 0!

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

// ...

// Per obj array index

let obj_index: u32 = 0;

vkCmdPushConstants(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

pipeline_layout,

VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

0,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

&obj_index as *const u32 as *const core::ffi::c_void

);

// Draw triangle without index buffer

// This does not even require you to bind an index buffer.

vkCmdDraw(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

3,

1,

0,

0

); // Uncommented this

// ...

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

Pay attention that we were very specific about the type of obj_index: u32! You don't want the compiler to turn it into for instance

a usize. If types do not match, vkCmdPushConstants may only read a portion of obj_index and may read the

wrong portion. For instance if the meaningful content gets stored in the lower 4 bytes and vkCmdPushConstants reads the upper 4 bytes.

This can become a minefield especially when uploading structs or arrays.

Our indexed triangle will be the second with object_index = 1.

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

// ...

// Per obj array index

let obj_index: u32 = 1;

vkCmdPushConstants(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

pipeline_layout,

VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

0,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

&obj_index as *const u32 as *const core::ffi::c_void

);

// Draw triangle with index buffer

vkCmdDrawIndexed(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

3,

1,

0,

0,

0

);

// ...

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

Our indexed quad will be the third with object_index = 2.

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

// ...

// Per obj array index

let obj_index: u32 = 2;

vkCmdPushConstants(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

pipeline_layout,

VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

0,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

&obj_index as *const u32 as *const core::ffi::c_void

);

// Draw quad with index buffer

vkCmdDrawIndexed(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

6,

1,

3,

3,

0

);

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

Adjusting the vertex shader

Now it's time to update our vertex shader to read the scene object's transform data and the camera data from the uniform buffer.

#version 460

struct CameraData

{

vec2 position;

float aspect_ratio;

};

struct ObjectData

{

vec2 position;

float scale;

};

const uint MAX_OBJECT_COUNT = 3;

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 0) uniform UniformData {

CameraData cam_data;

ObjectData obj_data[MAX_OBJECT_COUNT];

} uniform_data;

layout(push_constant) uniform ResourceIndices {

uint obj_index;

} resource_indices;

layout(location = 0) in vec2 position;

void main()

{

uint obj_index = resource_indices.obj_index;

vec2 obj_position = uniform_data.obj_data[obj_index].position;

float obj_scale = uniform_data.obj_data[obj_index].scale;

vec2 world_position = obj_position + position * obj_scale;

vec2 cam_position = uniform_data.cam_data.position;

float cam_aspect_ratio = uniform_data.cam_data.aspect_ratio;

vec2 view_position = (world_position - cam_position) * vec2(1.0/cam_aspect_ratio, 1.0);

gl_Position = vec4(view_position, 0.0, 1.0);

}

First we define CameraData and ObjectData. Both have a vec2 position,

and a float aspect_ratio for the camera and a float scale for the object. Following

std140 layout rules, this structure gets padded with an extra 4 bytes of unused data.

Then we define our uniform variable uniform_data. We specify the std140 layout, that it comes

from the 0th binding of the 0th descriptor set, and the data structure itself as well. The first 16 bytes

will hold the camera data, and the following three 16 bytes the scene object data.

Then we define our push constant holding our obj_index, which is a 32 bit integer.

In the main function we read the object transform, we multiply the vertex position with obj_scale,

uniformly scaling it, and translate it by adding obj_position. Then we subtract the camera position

to move it to view space, and divide the x coordinate with the aspect ratio.

We write the final result to gl_Position, and we are done.

I saved this file as 02_ubo_single_descriptor.vert into the shader_src/vertex_shaders

directory.

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/02_ubo_single_descriptor.vert.spv ./shader_src/vertex_shaders/02_ubo_single_descriptor.vert

Once our binary is ready, we need to load.

//

// Shader modules

//

// Vertex shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/02_ubo_single_descriptor.vert.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

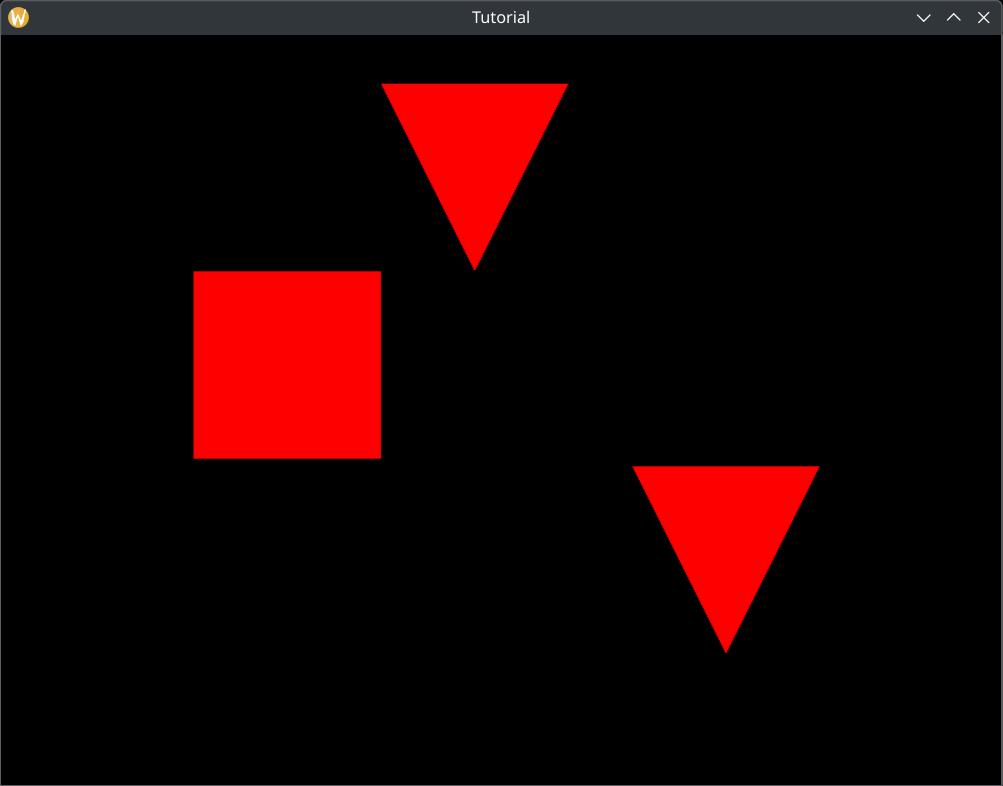

...and that's it! Now our application will render a whole scene! Sadly if you resize the new aspect ratio won't be uploaded, but that will change as you progress in this chapter.

The progress made so far is worth a sample application of its own. The sample code can be found here.

Moving objects every frame

Now we have a graphics application that draws a whole scene, but in a game you want things to move around every frame. Problem is, if we used the current single uniform buffer, and updated its content every frame, the content might end up being visible to the GPU rendering the previous frame. If we waited for the GPU to render the previous frame before we start writing new scene data, our GPU and CPU would not be utilized fully, because they would need to wait for each other. We wanted to avoid this problem with the sync primitives and the command buffers in the past, and we want to avoid it now.

The solution is creating separate uniform buffer regions for every frame. The principle is the same as with the sync primitives and the command buffers. Frame N has its dedicated uniform buffer region. When it starts rendering, it writes the camera object transforms into uniform buffer region N, records the command buffers and submits them. Frame N+1 starts. When it starts rendering, it writes its scene data into uniform buffer region N+1, which is separate from region N, and no data hazard happens.

In this tutorial the number of uniform buffer regions will match the frame_count, just as the

sync primitives and the command buffers. We can use the current_frame_index to identify the

right region.

This won't be very spectacular without moving objects. Let's name the scene object with the array index 0 the player object! The player object and the camera will be controllable with the keyboard.

So the summary of what we are going to do is:

-

We create separate uniform buffer region for every frame. The count will match

frame_count. -

At the beginning of each frame, after waiting for the rendering finished fence, we write the current

camera and scene object transform to the uniform buffer region identified by

current_frame_index. -

When recording, we pass

current_frame_indexand every uniform buffer region to the vertex shader. Then we read the right region from the vertex shader based oncurrent_frame_index.

Let's get started!

Uniform arrays

There are several approaches for binding different regions of a uniform buffer. You can create a different descriptor set for every frame. You can use dynamic uniform descriptors and supply a range when we bind them. Both of these approaches would leave the shader intact. We could use our already written shader unchanged.

Instead my approach will be using an array of uniforms, because this way I can introduce you to descriptor arrays, which is a very useful feature. So even though solving the minimalistic problem that we have could be done more easily, this new feature is very useful, so we learn that.

#version 460

struct CameraData

{

vec2 position;

float aspect_ratio;

};

struct ObjectData

{

vec2 position;

float scale;

};

const uint MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 8;

const uint MAX_OBJECT_COUNT = 3;

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 0) uniform UniformData {

CameraData cam_data;

ObjectData obj_data[MAX_OBJECT_COUNT];

} uniform_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

layout(push_constant) uniform ResourceIndices {

uint obj_index;

uint ubo_desc_index;

} resource_indices;

layout(location = 0) in vec2 position;

void main()

{

uint ubo_desc_index = resource_indices.ubo_desc_index;

uint obj_index = resource_indices.obj_index;

vec2 obj_position = uniform_data[ubo_desc_index].obj_data[obj_index].position;

float obj_scale = uniform_data[ubo_desc_index].obj_data[obj_index].scale;

vec2 world_position = obj_position + position * obj_scale;

vec2 cam_position = uniform_data[ubo_desc_index].cam_data.position;

float cam_aspect_ratio = uniform_data[ubo_desc_index].cam_data.aspect_ratio;

vec2 view_position = (world_position - cam_position) * vec2(1.0/cam_aspect_ratio, 1.0);

gl_Position = vec4(view_position, 0.0, 1.0);

}

One of the important differences is turning uniform_data into an array. Each array element will

identify a separate uniform buffer region. Its array size will be MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT, which

is a worst case higher bound. I assign 8 to it for now, because we will definitely not have 8

per frame regions.

The second one is passing along another push constant, ubo_desc_index, and we use it to index

into the current frame's uniform buffer region. Everything else is pretty much the same. This uniform variable

will be backed by a descriptor array.

Be careful that you cannot index into such an array with just any integer! The integer must be

the result of a

dynamically uniform expression!

Shader invocations are grouped into invocation groups. The definition of an invocation group is different

per shader stage. For rendering commands an invocation group encompasses every shader invocation that is launched

by the same rendering command. (In our case vkCmdDraw and vkCmdDrawIndexed)

An expression is dynamically uniform if it holds the same value within an invocation group.

Indexing into uniform_data is safe with ubo_desc_index, because it holds the same

value within a draw call, but for instance you cannot index into uniform_data

trivially with a vertex attribute, or if you experimented with instanced rendering, gl_InstanceIndex,

unless you ensure that they have the same value within the invocation group.

If you want to do that, you need to study and use descriptor indexing and nonuniform qualifier, see a

document on descriptor indexing

and the GLSL extension GL_EXT_nonuniform_qualifier.

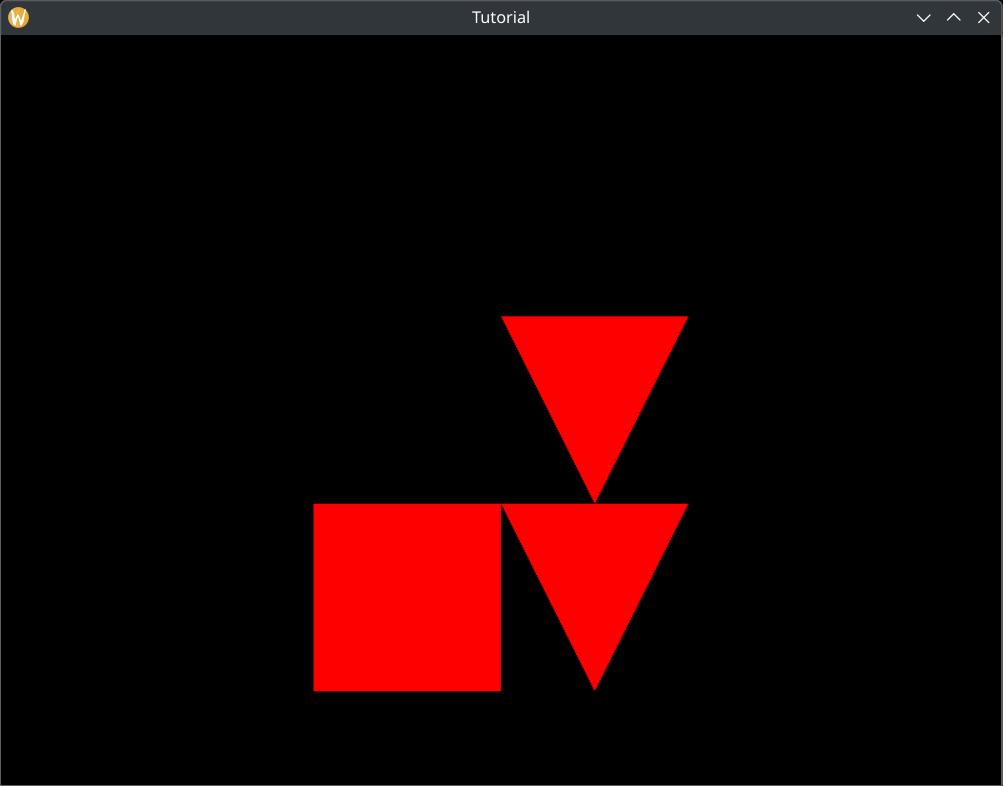

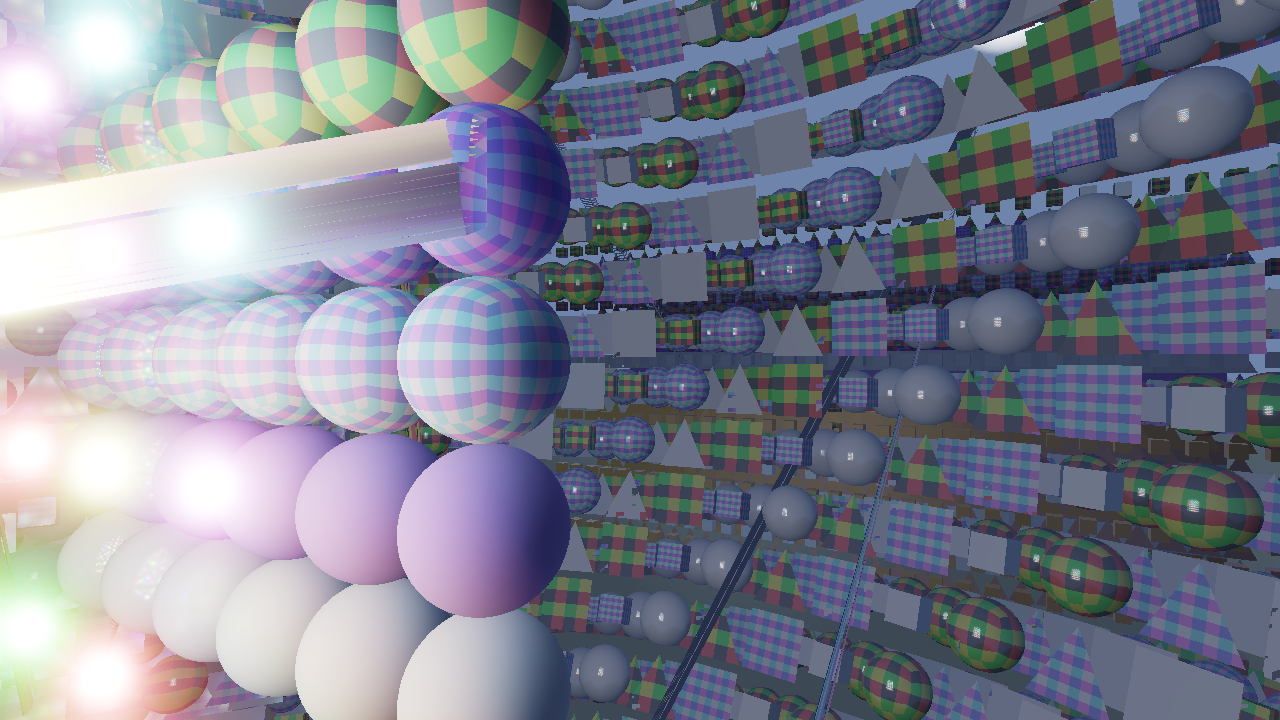

If you index into a descriptor array with a non-dynamically uniform variable, you might see rendering bugs like the ones below on some architectures (like AMD). Shaders might read the wrong uniform buffer region due to how the hardware works.

Very similar bugs just with textures can be seen in the stackoverflow questions here and here.

I saved this file as 03_ubo_per_frame_descriptor.vert into the shader_src/vertex_shaders directory.

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/03_ubo_per_frame_descriptor.vert.spv ./shader_src/vertex_shaders/03_ubo_per_frame_descriptor.vert

Once our binary is ready, we need to load.

//

// Shader modules

//

// Vertex shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/03_ubo_per_frame_descriptor.vert.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

Checking for dynamic indexing support

Indexing into an array of descriptors with a dynamically uniform expression may or may not be supported on

some cards. Any decent desktop GPU should support it, but some mobile GPU may not. In any case you should

check the queried phys_device_features whether shaderUniformBufferArrayDynamicIndexing

is set to VK_TRUE

//

// Checking physical device capabilities

//

// ...

// Getting physical device features

let mut phys_device_features = VkPhysicalDeviceFeatures::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetPhysicalDeviceFeatures(

chosen_phys_device,

&mut phys_device_features

);

}

if phys_device_features.shaderUniformBufferArrayDynamicIndexing != VK_TRUE

{

panic!("shaderUniformBufferArrayDynamicIndexing feature is not supported.");

}

You also need to enable the same feature during device creation if you want to use it.

It is done by setting shaderUniformBufferArrayDynamicIndexing to VK_TRUE.

//

// Device creation

//

// ...

let mut phys_device_features = VkPhysicalDeviceFeatures::default();

// Enabling requested features

phys_device_features.shaderUniformBufferArrayDynamicIndexing = VK_TRUE;

// ...

Adjusting uniform buffer

We make our buffer large enough to contain the per object data of several frames, and ranges within the single buffer will hold individual per frame region data. Descriptor sets can refer to a region of a buffer with an offset, so we can create a descriptor per region, and have them refer to different offsets within the buffer.

Pay attention that when you are binding an uniform buffer range with an offset, as we will do,

the offset must align to the minUniformBufferOffsetAlignment device limit. If the size of the

scene data is not a multiple of this parameter, we must add padding to it.

We will have multiple regions in the same buffer.

//

// Uniform data

//

// ...

let max_object_count = 3;

let frame_data_size = core::mem::size_of::<CameraData>() + max_object_count * core::mem::size_of::<ObjectData>();

// Instead of this...

//let uniform_buffer_size = frame_data_size;

// ...let's write it like this!

let min_ubo_offset_alignment = phys_device_properties.limits.minUniformBufferOffsetAlignment as usize;

let ubo_alignment_rem = frame_data_size % min_ubo_offset_alignment;

let frame_data_padding = if ubo_alignment_rem != 0 {min_ubo_offset_alignment - ubo_alignment_rem} else {0};

let padded_frame_data_size = frame_data_size + frame_data_padding;

let uniform_buffer_size = frame_count * padded_frame_data_size;

// ...

First we calculate the per frame data size of a single region, as we did previously, but then instead of setting

it to be the buffer size, we check if it's an integer multiple of minUniformBufferOffsetAlignment.

If not, we increase its size so it will be. This will be padded_frame_data_size. The final size is

calculated by multiplying it with frame_count. This way it will be large enough to hold a region

for every frame, and offsetting with N * padded_frame_data_size will satisfy the alignment

requirements.

Descriptor arrays

In the shader we have created an array of uniform variables. The way we bind regions of our uniform buffer to every one of them is descriptor array. Descriptor sets can contain an array of descriptors for every binding. So far we only had one uniform variable and a single descriptor defining its data source. An uniform variable array can be defined with an array of descriptors.

Adjusting descriptor set layout

Let's adjust the descriptor set layout!

//

// Descriptor set layout

//

let max_ubo_descriptor_count = 8; // We adjusted this

let layout_bindings = [

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding {

binding: 0,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

descriptorCount: max_ubo_descriptor_count,

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

pImmutableSamplers: core::ptr::null()

}

];

let descriptor_set_layout_create_info = VkDescriptorSetLayoutCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_DESCRIPTOR_SET_LAYOUT_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

bindingCount: layout_bindings.len() as u32,

pBindings: layout_bindings.as_ptr()

};

// ...

Instead of setting descriptorCount be one, we set it to a larger number, in this case

8. We would need to adjust the uniform descriptor count of the descriptor pool as well,

but it's already using the variable max_ubo_descriptor_count, so that one is handled with

this as well. Since descriptor allocation knows the descriptor set layout during allocation, the

allocated descriptor set will have the right amount of descriptors in the 0th binding.

Resizing push constant range

Then we need to supply an integer as push constant to index into the descriptor array.

//

// Pipeline layout

//

// Object ID + Frame ID

let push_constant_size = 2 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32;

let push_constant_ranges = [

VkPushConstantRange {

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

offset: 0,

size: push_constant_size,

}

];

// ...

There. Nothing more is needed than increasing push_constant_size to hold tow 32 bit integers.

Filling descriptors

Now let's write the new array elements of the descriptor array! Every descriptor must refer to the region of the corresponding frame.

//

// Descriptor pool & descriptor set

//

// Writing descriptor set

let mut ubo_descriptor_writes = Vec::with_capacity(max_ubo_descriptor_count as usize);

for i in 0..max_ubo_descriptor_count

{

let ubo_region_index = (frame_count - 1).min(i as usize);

ubo_descriptor_writes.push(

VkDescriptorBufferInfo {

buffer: uniform_buffer,

offset: (ubo_region_index * padded_frame_data_size) as VkDeviceSize,

range: frame_data_size as VkDeviceSize

}

);

}

let descriptor_set_writes = [

VkWriteDescriptorSet {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_WRITE_DESCRIPTOR_SET,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

dstSet: descriptor_set,

dstBinding: 0,

dstArrayElement: 0,

descriptorCount: ubo_descriptor_writes.len() as u32,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

pImageInfo: core::ptr::null(),

pBufferInfo: ubo_descriptor_writes.as_ptr(),

pTexelBufferView: core::ptr::null()

}

];

println!("Updating descriptor sets.");

unsafe

{

vkUpdateDescriptorSets(

device,

descriptor_set_writes.len() as u32,

descriptor_set_writes.as_ptr(),

0,

core::ptr::null()

);

}

// ...

Now we learn how to write a consecutive array of descriptors within a binding. We only modify

ubo_descriptor_writes Instead of pushing a single value, we push one for every descriptor array

element. In every VkDescriptorBufferInfo we bind neighboring scene data with

N * padded_frame_data_size offsets.

If we have less frames than descriptor array elements, we fill the remaining descriptors with the last frame's buffer region. Leaving the descriptor uninitialized would lead to validation errors.

We don't have to modify our VkWriteDescriptorSet, because we already set it up well previously.

Now that we have every setup needed before the game loop, it's time to start adding things to the game loop.

Keyboard input

Now we are going to handle keyboard events so we can control the player object and the camera.

First we create some state before our game loop.

//

// Game state

//

// ...

//

// Game loop

//

// ...

Before the game loop we need booleans to store whether a key is pressed.

//

// Game state

//

// Input state

let mut obj_forward = false;

let mut obj_backward = false;

let mut obj_left = false;

let mut obj_right = false;

let mut cam_forward = false;

let mut cam_backward = false;

let mut cam_left = false;

let mut cam_right = false;

// ...

//

// Game loop

//

// ...

Also before the game loop we need object and camera positions to modify in case a key is pressed.

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

let mut obj_x = 0.25;

let mut obj_y = 0.25;

let mut cam_x = 0.0;

let mut cam_y = -0.25;

//

// Game loop

//

// ...

Now let's get inside our game loop, to the event handling logic which looks like this...

//

// Game loop

//

// ...

let mut event_pump = sdl.event_pump().unwrap();

'main: loop

{

for event in event_pump.poll_iter()

{

match event

{

sdl2::event::Event::Quit { .. } =>

{

break 'main;

}

sdl2::event::Event::Window { win_event, .. } =>

{

if let sdl2::event::WindowEvent::Resized(new_width, new_height) = win_event

{

let new_width = new_width as u32;

let new_height = new_height as u32;

if new_width != width || new_height != height

{

width = new_width;

height = new_height;

recreate_swapchain = true;

}

}

}

_ =>

{}

}

}

// ...

}

Here we need to react to two new kinds of events: the key pressed and key released event.

Here we add the key pressed event.

for event in event_pump.poll_iter()

{

match event

{

sdl2::event::Event::Quit { .. } =>

{

break 'main;

}

sdl2::event::Event::Window { win_event, .. } =>

{

if let sdl2::event::WindowEvent::Resized(new_width, new_height) = win_event

{

let new_width = new_width as u32;

let new_height = new_height as u32;

if new_width != width || new_height != height

{

width = new_width;

height = new_height;

recreate_swapchain = true;

}

}

}

sdl2::event::Event::KeyDown { keycode: Some(keycode), .. } =>

{

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::W

{

obj_forward = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::S

{

obj_backward = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::A

{

obj_left = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::D

{

obj_right = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::U

{

cam_forward = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::J

{

cam_backward = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::H

{

cam_left = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::K

{

cam_right = true;

}

}

_ =>

{}

}

}

The enum variant encoding a key pressed event is KeyDown.

The keycode field stores which key was pressed. We assign the ASDF keys to the player object and

the UJHK keys to the camera. If the right key is pressed, we set the right boolean to true, so

later in the game logic we can move our player and camera around.

Then we add the key released event.

for event in event_pump.poll_iter()

{

match event

{

sdl2::event::Event::Quit { .. } =>

{

// ...

}

sdl2::event::Event::Window { win_event, .. } =>

{

// ...

}

sdl2::event::Event::KeyDown { keycode: Some(keycode), .. } =>

{

// ...

}

sdl2::event::Event::KeyUp { keycode: Some(keycode), .. } =>

{

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::W

{

obj_forward = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::S

{

obj_backward = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::A

{

obj_left = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::D

{

obj_right = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::U

{

cam_forward = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::J

{

cam_backward = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::H

{

cam_left = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::K

{

cam_right = false;

}

}

_ =>

{}

}

}

The enum variant we are looking for is KeyUp. The basic idea is the same, but the booleans are

instead set to false.

After the event handling logic we add our new game logic where we update the game state using the boolean variables.

//

// Game loop

//

// ...

let mut event_pump = sdl.event_pump().unwrap();

'main: loop

{

for event in event_pump.poll_iter()

{

// ...

}

//

// Logic

//

if obj_forward

{

obj_y -= 0.01;

}

if obj_backward

{

obj_y += 0.01;

}

if obj_left

{

obj_x -= 0.01;

}

if obj_right

{

obj_x += 0.01;

}

if cam_forward

{

cam_y -= 0.01;

}

if cam_backward

{

cam_y += 0.01;

}

if cam_left

{

cam_x -= 0.01;

}

if cam_right

{

cam_x += 0.01;

}

// ...

}

Now that our game state is updated, we need to upload the right transforms into the right uniform buffer region every frame and draw.

Updating the region of the current frame!

This time we are uploading the scene every frame.

Previously we uploaded uniform data before the game loop. That part of the code should be deleted. Now we no longer need it.

//

// Uniform upload

//

// All of this must die...

let camera_data;

let object_data_array;

unsafe

{

let camera_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<CameraData> = core::mem::transmute(

uniform_buffer_ptr

);

camera_data = &mut *camera_data_ptr;

let object_data_offset = core::mem::size_of::<CameraData>() as isize;

let object_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<ObjectData> = core::mem::transmute(

uniform_buffer_ptr.offset(object_data_offset)

);

object_data_array = core::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(

object_data_ptr,

max_object_count

);

}

// ...

object_data_array[2] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

ObjectData {

x: -0.25,

y: 0.25,

scale: 0.25,

std140_padding_0: 0.0

}

);

// ...up to this point.

// ...

Instead we place a refined version inside the game loop after we waited for the frame finished fence.

//

// Rendering

//

// ...

//

// Waiting for previous frame

//

// ...

//

// Uniform upload

//

// Getting references

let camera_data;

let object_data_array;

unsafe

{

let per_frame_region_begin = uniform_buffer_ptr.offset(

(current_frame_index * padded_frame_data_size) as isize

);

let camera_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<CameraData> = core::mem::transmute(

per_frame_region_begin

);

camera_data = &mut *camera_data_ptr;

let object_data_offset = core::mem::size_of::<CameraData>() as isize;

let object_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<ObjectData> = core::mem::transmute(

per_frame_region_begin.offset(object_data_offset)

);

object_data_array = core::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(

object_data_ptr,

max_object_count

);

}

*camera_data = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

CameraData {

x: cam_x,

y: cam_y,

aspect_ratio: width as f32 / height as f32,

std140_padding_0: 0.0

}

);

object_data_array[0] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

ObjectData {

x: obj_x,

y: obj_y,

scale: 0.25,

std140_padding_0: 0.0

}

);

object_data_array[1] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

ObjectData {

x: 0.25,

y: -0.25,

scale: 0.25,

std140_padding_0: 0.0

}

);

object_data_array[2] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

ObjectData {

x: -0.25,

y: 0.25,

scale: 0.25,

std140_padding_0: 0.0

}

);

Most of the data is very similar, but the player object and the camera is now copied from the game state.

Frame index in push constants

Now we upload the index of the uniform buffer descriptor binding our region in the current frame, which is the current frame index.

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

// ...

// Setting per frame descriptor array index

let ubo_desc_index: u32 = current_frame_index as u32;

vkCmdPushConstants(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

pipeline_layout,

VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

&ubo_desc_index as *const u32 as *const core::ffi::c_void

);

// Here comes every draw call

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

And that's it! Nothing else is needed.

This is also available as a separate sample application. The source code can be found here.

Bonus: Using Vertex and Index buffers

In the vertex and index buffer chapter I already mentioned the concept of draw call batching and how rendering small models with a single draw call may lead to better hardware utilization. Also at the beginning of this chapter I mentioned that without uniform buffers you would need to upload the transformed vertices of every scene element into vertex and index buffers.

This approach may actually be preferable if the models are tiny. (If they do not have enough vertices to fill up

a warp on NVidia or a wavefront on AMD, like below 64 or 32 triangles.) You can replicate models, transform them and

upload them into vertex and index buffers, and maybe even draw them with a single vkCmdDrawIndexed.

The Cherno made a video series in OpenGL about combining many small models into a single draw call in his batching series. Transforming every vertex on the CPU and uploading the new vertices and indices might not be very modern and efficient anymore, but you may learn advanced features such as multi draw indirect and compute shaders, and combine them with the basic idea.

Pay attention, that some of the things that the Cherno does in OpenGL cannot be done so trivially in Vulkan! For instance in this series his texturing code would be backed by combined image sampler descriptors (that we will learn in the next chapter) and it can only be indexed with dynamically uniform expressions. He uses a vertex attribute, which will not be dynamically uniform. In Vulkan this will be buggy. Also in OpenGL he does not use different buffers per frame or per frame buffer regions like we did with the uniform buffer, but in Vulkan it will be necessary! Dynamic geometry that can be modified every frame must be mirrored for every frame in flight! You must do your homework if you want to adapt his tutorial!

I called your attention to this approach because it is viable in some cases, however some cases involve advanced topics and adress special cases. Instead we are going to address the case where you have large models that should not be replicated, and introduce ourselves to a new type of Vulkan buffer, Uniform buffers.

Bonus: bind everything approach

The reason why I introduced descriptor arrays is the bindless or bind everything approach that many engines took. AMD has the Vulkan fast paths slides where they recommend having a single huge descriptor set that refers to every resource used, and binding this descriptor set once. In their presentation they illustrate this on textures, which we will cover in the next tutorial, but aside from that they also use uniform arrays and descriptor arrays, and we have seen it working for uniform buffers as well.

Id Software took this approach in Doom Eternal, when they merged multiple draw calls into a single draw call, and had to access the textures of many scene objects that were merged into the same draw call. Again, doing this with draw call merging is non-trivial and you should study descriptor indexing and nonuniform qualifier, basically this document and this GLSL extension if you want to do that.

Even Apple recommends data structures to describe the whole scene in the GPU driven rendering segment of their Modern Rendering with Metal presentation, although their graphics API, Metal has different building blocks than Vulkan.

Quantic Dream also took a "bindless" (bind everything) approach to binding textures and buffers in the PC port of their Detroit Become Human. They explain this in detail in their blog post on OpenGPU.

Bonus: descriptor buffer extension

In this tutorial we used descriptor pools, but it felt like just managing memory hidden away by Vulkan. On some GPUs descriptors are implemented in such a way that managing descriptors is literally about managing memory, and Descriptor Buffer extension allows you to take advantage of this. This is an interesting subject for advanced graphics programmers.

Bonus: descriptor indexing

Vulkan offers features for indexing descriptors with non-dynamically uniform expressions and removing the

necessary upper bound for descriptor arrays, such as we have seen with our shader constant

MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT. I have already mentioned descriptor indexing, and I have already linked

a document on descriptor indexing

and the GLSL extension GL_EXT_nonuniform_qualifier.

Beyond that ARM has a

blog post

about descriptor indexing. Again, this is an advanced feature, but one day you may want to check it out.

Bonus: dynamic uniform descriptors

My descriptor array approach may not be suitable for your use case. For instance your target hardware may not

support it. In this case you could use this alternative.

You could use VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER_DYNAMIC descriptor type and bind with an offset to

bind the frame specific portion of the buffer as well. You can find C++ example code and a summary

here.

Wrapping up

This was quite massive. We learned about uniform buffers, descriptors and descriptor sets. We allocated descriptor sets from descriptor pools, and represented multiple uniform buffer regions with descriptor arrays. We also learned about push constants and finally understand what pipeline layouts are good for. These are a lot of concepts to learn.

We also followed a previously introduced principle of having multiple frames in flight have exclusive access to their data.

The result is being able to draw a scene made out of many scene objects, some of them referring to the same model in the vertex and index buffers.

The next step is to add texturing.

For the sake of completeness, the sample code for the single descriptor version can be found here.

For the final application with per frame descriptors, the sample code can be found here.

The tutorial continues here.