Environment mapping

In the previous chapter we have learned what cube images are and how to use them by drawing a skydome.

In this chapter we will implement an indirect illumination technique called environment mapping using cube images. We will add the contribution of radiance coming from the sky to the radiance reflected from a surface. To do that we will learn about Monte Carlo integration and its application in environment mapping.

This tutorial is math and physics heavy and assumes you already have some intuition for calculus. The recommendations from the previous tutorials for consuming math still apply: you can understand math in many ways, depending on your way of thinking and background:

- Read and understand the math first, then the code

- Understand the code first, and then interpret the math

Read whichever way is better for you. Be prepared that multiple rereads may be necessary.

This tutorial is in open beta. There may be bugs in the code and misinformation and inaccuracies in the text. If you find any, feel free to open a ticket on the repo of the code samples.

Theory

In the diffuse lighting chapter we explicitly ignored indirect illumination, and this resulted in ugly metallic objects in the specular lighting chapter. Now it's time to revisit the rendering equation and put some indirect lighting back to our simplified model using light probes.

Let's remember that the rendering equation looks like this:

This is a generic integral with an infinite recursion inside it. Our computers cannot handle integrals and infinite recursions, so we specialized this model to render our scene in real time.

We removed shadow casting, introduced point lights, inserted a specific BRDF into the rendering equation, and most importantly, removed indirect illumination, cutting off the infinite recursion. The result was the following:

Now we need to reintroduce some kind of an indirect illumination to make sure metallic objects won't be black. Reflected radiance from additional light sources simply add up, so let's model indirect illumination as an added term given by integrating reflected radiance coming from the environment like this.

Basically we appended this extra radiance coming from indirect illumination:

We need to find some way to calculate a value for this term. Let's remember the requirements we had in the diffuse lighting chapter! We wanted to avoid solving a generic integral and wanted to avoid interdependencies between scene elements. This removed lots of cases that we would have needed to account for and increased our performance.

It turns out that we must evaluate an integral somehow, and there is a field of study called numerical analysis that provides algorithms for approximate soultions for integrals. Here we will simplify the above indirect illumination integral, calculate some of its partial results and store them in textures.

Some of those results correspond to directions, and this is where cube images from the previous chapter come in. They stored data in six images and made it addressable with a 3D direction vector.

Light probes

Light probes store the indirect illumination calculated from a specific point of the scene in a cube image. During rendering indirect illumination is read from the light probes that affect our surface element.

This solution does not create interdependencies between models during rendering. You can load light probes from file or calculate them during runtime by for instance rendering the scene or certain scene elements onto a cubemap.

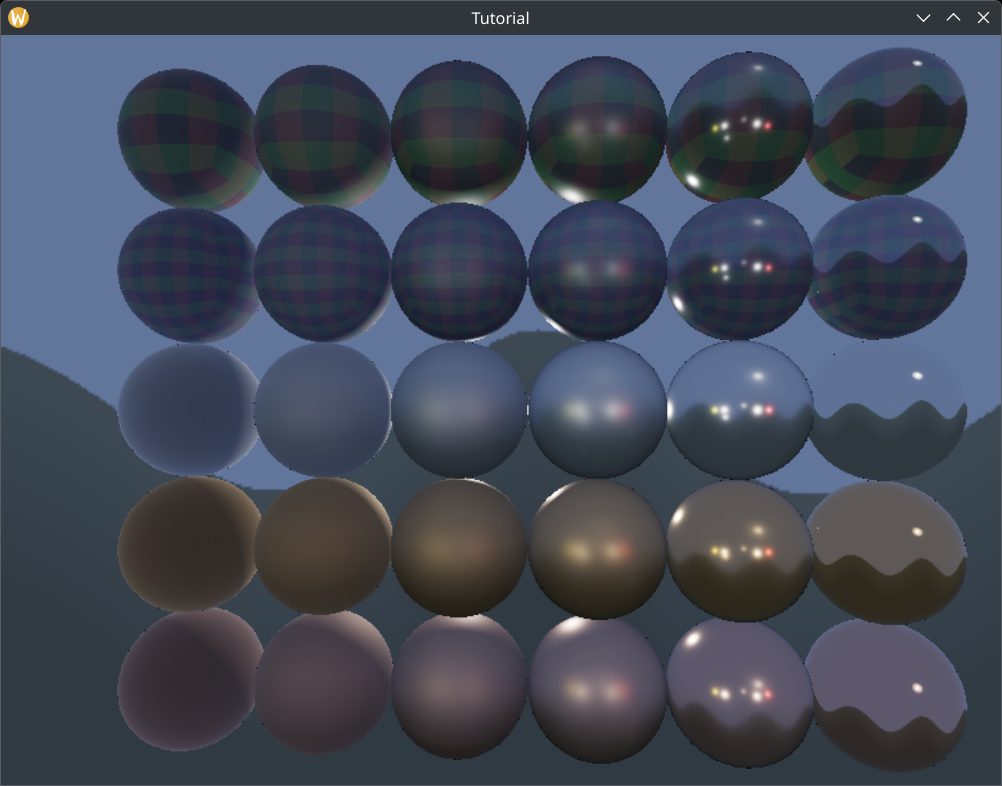

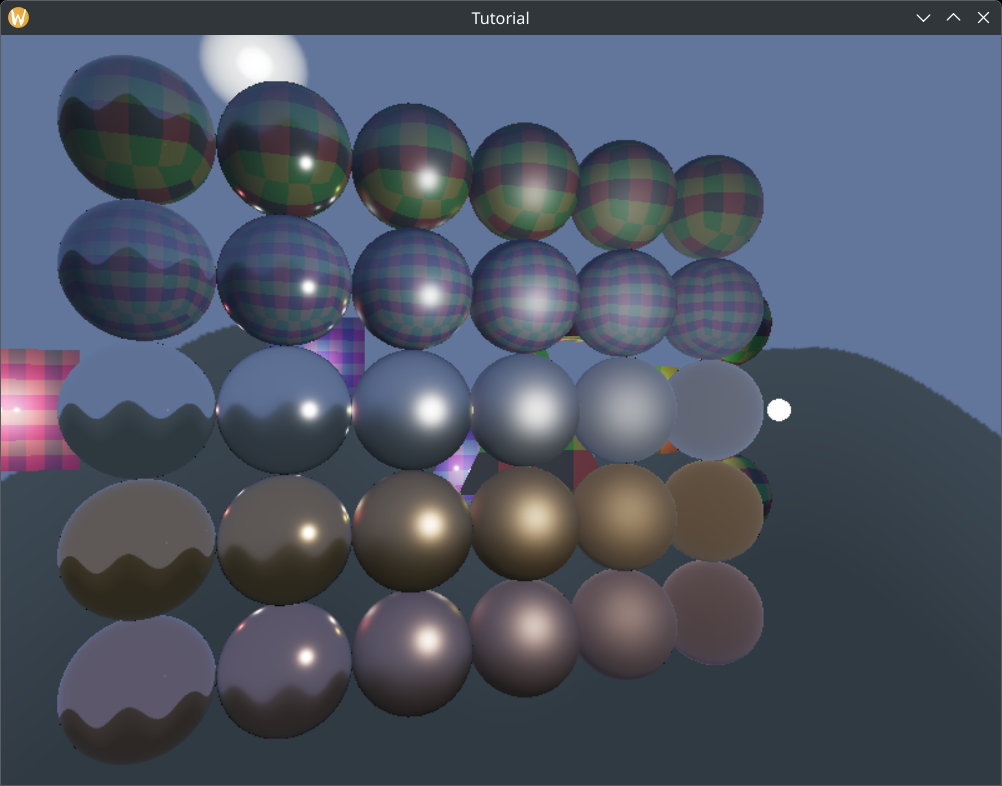

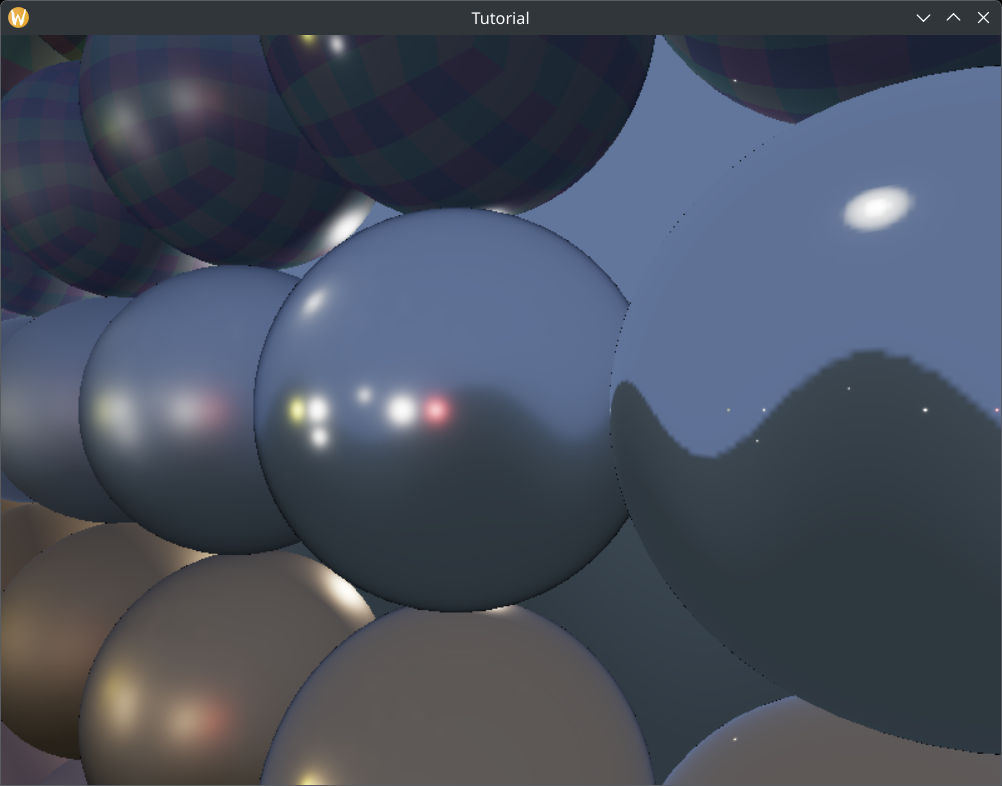

The indirect illumination will be different for rough and smooth surfaces.

As we can see, rough surfaces become blurry, because they reflect light from many different directions. More blurry reflections can be stored in lower resolution images, because they do not have high frequency changes that require more dense sampling.

We can take advantage of mipmapping, a feature that allows storing the progressively downscaled versions of an image, and smoothly transitioning between them during sampling. During image creation we can specify the number of mip levels that we want, and later fill it with lower resolution data.

The indirect illumination data for higher roughness values can be stored in lower mip levels, and Vulkan allows us to linearly blend them for roughness values in-between.

In the following sections we are going to simplify the newly added indirect illumination integral until it can be performed on a computer and its partial results can be stored in 2D images and cube images. In this tutorial we will have a single light probe, but much of the theory works for many light probes so it is phrased as if there were multiple light probes.

Monte Carlo integration

Solving an integral analytically is not something computers are capable of, at least not with the kind of function that is inside the rendering equation, so numerical analysis comes to the rescue. We can approximate the integral of the indirect illumination using Monte Carlo integration.

Integrating a function over a domain can be approximated with the following formula:

Where is a probability density

function, is an integer number and for every integer

This formula works best when the probability density function gives high probability to the parts of the function where there is high frequency change and the sample points also cluster around these parts. This way parts with high frequency changes can be sampled and averaged accurately, and parts with lower frequency changes can be undersampled.

Let's get a feel for the reasoning behind Monte Carlo integration! Now I'm going to throw around terminology from probability theory. Feel free to learn about it and digest it if things get fuzzy! Let be the function we want to integrate! The integral would look like this:

Let's multiply and divide it with a function! Let's call this function ! This does not alter the integral's value as long as the function does not do exotic things.

If this function is a probability density function, then this formula can be interpreted as the expectance value of the function.

Applying an approximation from mathematical statistics, if we take samples according to the density function p, the expectance value can be approximated with the average of the function evaluated at the sample points.

The resulting formula is our numerical method. It's a simple sum, we can choose and will be whatever that is inside the indirect illumination integral. A simple sum with two function that we can evaluate can be implemented on today's computers. When applying this method to the indirect illumination integral, we get the formulae present in the Unreal Engine 4 doc and the Frostbite doc.

We aren't quite there yet, because is still unspecified. The Frostbite doc chooses this to be a function of the NDF function:

Now the integral sign is gone and what remains is a simple sum that is computable.

Now let's work on it a bit so we can evaluate it and store it in images! Images can be 2D images, cube images, 3D images, image arrays, etc. and the thing they have in common is that they cannot be addressed by a vector of arbitrary dimensions, only 2D vectors, 3D vectors, etc., so they can only store sample points of 2D, 3D, etc. functions. What we have in the integral is way more than that, so we either have to approximate to get rid of variables, or try to split it into partial results and store those in images. Let's see what steps can be taken!

Removing view dependency

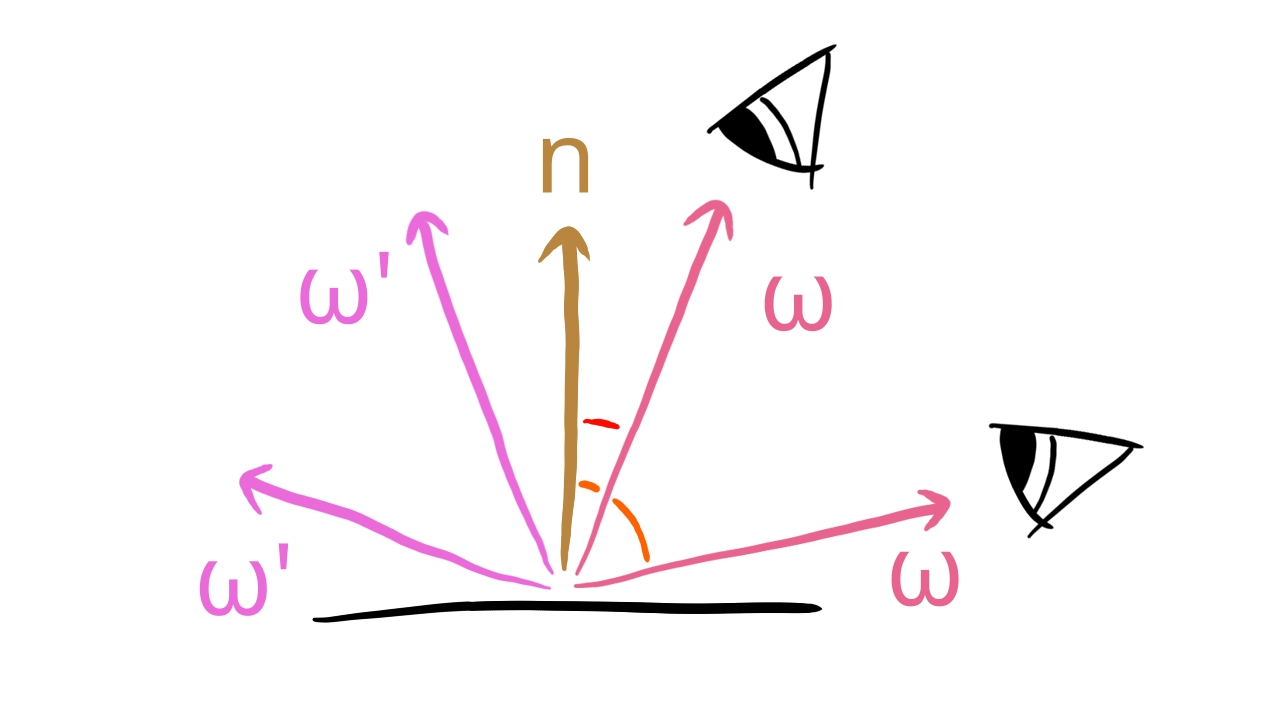

In general reflections depend on two parameters: a view direction and a normal vector. Calculating a direction of reflection is a function of both parameters.

The Frostbite doc in section 4.9.1.2 removes view dependency as an approximation. Let's assume that the camera direction points towards the normal vector. This leads to a huge flaw in our integration especially when the angle between the view direction and the normal vector is large.

The benefit is the removal of view dependence, reducing the amount of variables inside the integral.

Now let's see what we can do about the remaining variables!

Split sum approximation

We still have problems with storing the results in textures. The integral depends on the x, y and z coordinates of the normal vector, and the value of the BRDF depends on the roughness and the nomal vector. Cube images can map data to a direction and a mip level, and 2D images can map data to a 2D vector and a direction. We still need to work on the formula to store results in images.

Let's find the next opportunity for simplification by plugging the Cook-Torrance BRDF into the formula!

Since we assume that the normal vectors, the half vectors and the direction vectors are unit length, the dot product in the divisor will be equal to the cosine in the divident, and they will cancel out.

Then let's plug the probability function derived from the NDF into the equation!

The constant and the NDF will cancel out.

Now we have the BRDF and the incoming light multiplied together inside the sum. Here comes the approximation: let's integrate the incoming light from different directions and the BRDF value from different directions, and let's multiply them together!

This changes the previous Monte Carlo integral into two integrals: one for the light dependent LD term and one for the material data, normal and view direction dependent DFG term. The individual partial results can finally be stored in textures. The individual terms' formula is below.

The LD term is the preintegrated light contribution in a given point for every direction, and it can be stored in a cubemap. For increasing roughness the cubemap contents become more blurry, so they can be stored in a mipmapped cubemap's lower resoultion mip levels. Notice that the new LD term is weighed by the dot product between the sample direction and the normal vector. If you are curious, find the relevant chapters in the Frostbite doc and the Unreal Engine 4 doc for details.

The DFG term depends on the , the roughness and the dot product of the normal vector and the view vector. Both the Frostbite doc and the Unreal Engine 4 doc works on this formula a bit, and the can be factored out of the integral, leaving only the roughness and the dot product of the normal vector and the view vector. The steps are the following:

Let's substitute the Schlick approximation into the equation!

Let's relabel two subexpression in the above equation!

With these variables the above equation looks like this:

Now let's rearrange the equation a bit:

Simply reordering the last part will be the following:

Now the term falls into two sums and only the first one contains . The last step is the following:

Now the two sums only depend on the roughness and the dot product between the normal and the view vector. These are two scalar values, and the result of these two sums can be stored in two components of a 2D texture.

Only the LD term is dependent on the lighting condition, so that's the only thing we need to calculate and store in a cube image for every light probe. (These are also called pre filtered environment cubemaps.) The DFG term can be computed once and reused for every light probe.

Conceptually the technique is about creating cubemaps for selected points in space, integrate the LD term, the preintegrated incoming radiance arriving at this point, and use it as indirect illumination data in the vicinity of the selected point. In this tutorial we will have a single cubemap for a single point, the incoming radiance is the radiance coming from the skydome, and this data will be used to calculate indirect illumination everywhere on the scene.

Now that we rearranged and approximated our formula until the results can be stored in images, we need to do one final thing that is necessary for a Monte Carlo integration: we need to generate sample directions.

Generating sample directions

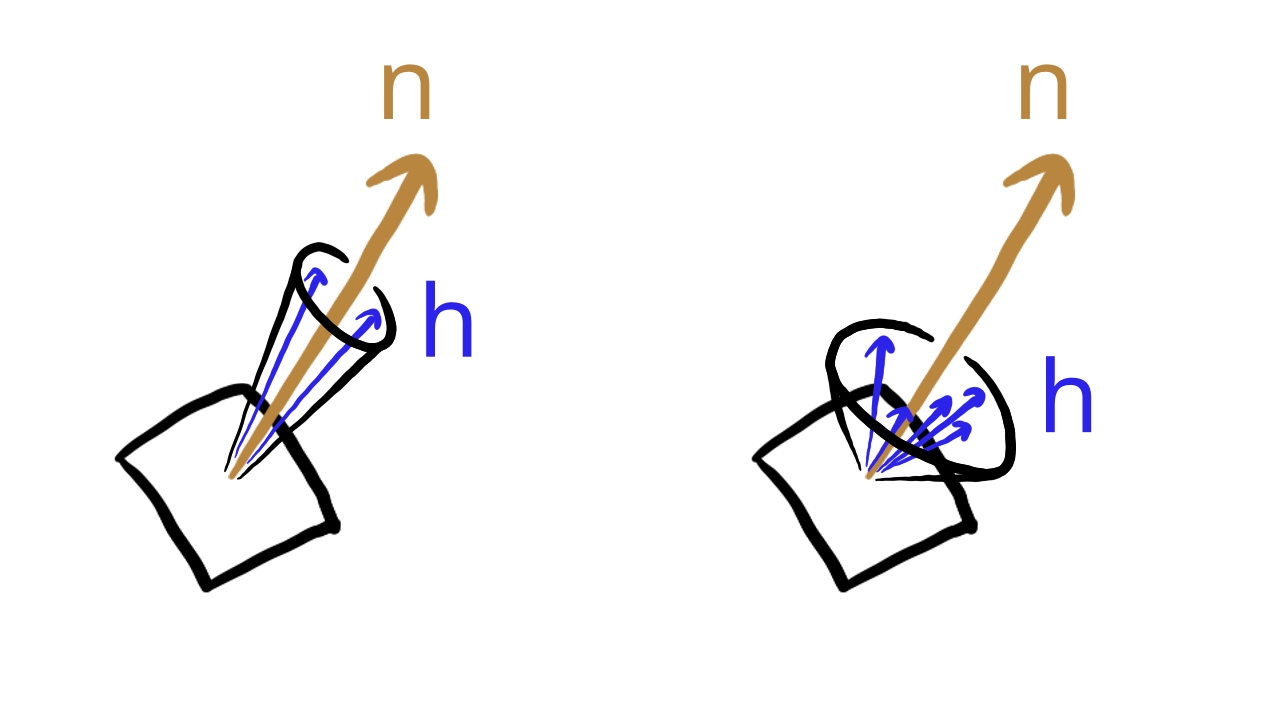

Monte Carlo integration requires sample points, so it's time to discuss how to generate pseudorandom directions to use as light directions and calculate their half vectors. These directions need to be more spread out for more rough materials. The basic idea is to generate a set of random 2 dimensional float vectors, then use these as parameters to generate vectors within a cone, and use the roughness parameter to widen this cone. Then transform these directions into the coordinate system of the surface element!

Hammersley sets

First let's generate a set of 2 dimensional float vectors! This is where Low Discrepancy Sequences come in handy. The Unreal Engine 4 doc used the Hammersley set, so this is what we are going with.

Let the number of samples be ! The th sample point will be generated the following way:

- The coordinate will be .

- The coordinate will be the Van der Corput inverse of .

The basic idea of the Van der Corput inverse is:

- Let's write down our number in base !

- Let's mirror this number to the decimal dot!

We can express this with a formula. Let be a positive integer number that is written down in base like this:

It's Van der Corput inverse is given by this formula:

Our choice for base will be , so we take the binary number, and mirror it to the decimal dot, getting a number less than one.

Generating sample directions

Now that we have a random 2D point set, we want to turn these into directions around a normal vector that can be more spread out based on the roughness of the material. This can be achieved using a following formula from the Unreal Engine 4 doc. The basic idea is to generate half vectors in a cone around the normal vector. The larger the roughness is, the wider the cone gets. For the Hammersley set element corresponding to the given sample point the sample half vector is given by the following formula.

This formula gives us half vectors in the local coordinate system of the surface element. We need to transform it to the coordinate system of the surface element!

As we have already discussed in the 3D chapter, transforming a coordinate vector can be done by transforming the base vectors and taking their linear combination with the coordinate vector's coordinates. Let's define the local coordinate system's vectors to be the orthonormal unit vectors! We want the vector to be transformed to the normal vector, and we want to transform the other two into an orthogonal pair of unit vectors in the plane perpendicular to the normal vector. We can do that by defining an UP vector as , or if this is parallel to the normal, then , and get two orthogonal vectors in the said plane by taking some cross products. These will be the surface tangents for a surface element with the given normal. We can define these as the transformed and vectors. The transformed vectors will be the following:

- The transformed vector will be the tangent vector given by the cross product of the normal vector and the up vector.

- The transformed vector will be the tangent vector given by the cross product of the normal vector and the tangent x vector.

- The transformed vector will be the normal vector.

We can use this coordinate system to transform our half vectors into the cone surrounding the normal vector.

Now we have sample directions around the normal vector in the right coordinate system. We can plug these both into the LD and the DFG generation integrals.

Putting it all together

Now that we have covered everything piece by piece, let's assemble the pieces into an indirect illumination technique!

At the beginnig of the chapter we put a rendering equation for indirect illumination back into the integral. The problem is that computers cannot solve it, so we tried to find some numerical solution. This lead us to Monte Carlo integration.

We wrote down the equation to numerically solve the new integral using Monte Carlo integration. We acquired a sum instead of the integral, which can at least be implemented on a computer. Then we took our BRDF and a probability function based on our NDF and plugged it into the equation. This gave us opportunities to rearrange the Monte Carlo integral and perform some approximations to find partial results that can be precomputed and stored in images. We had the term for preintegrating material specific data and storing it in a 2D image, and an term for preintegrating lighting specific data and storing it in a cube image.

Then we found the last missing puzzle piece for a Monte Carlo integral: pseudorandom directions. We generalted low discrepancy sequences to generate 2D vectors, and calculated 3D direction vectors around a cone. Then we transformed the new direction vectors into the normal vector's frame of reference, and we can use these as half vectors within a microfacet. For every half vector there will be an exact matching light direction in the mirror direction, so now we have sample directions for the Monte Carlo integral.

We already have a cubemap that contains incoming radiance from every direction: the skydome. In this tutorial the single LD cubemap will contain the preintegrated radiance coming from the sky, and we will calculate indirect illumination for every point in space based on this LD cubemap.

The whole process requires the following steps:

-

We will preintegrate the term and store it in a 2D image.

- We generate random half vectors with Hammersley sets and the cone formula.

- We plug these half vectors into the sum of the term and calculate the integral for many view angles and roughness values.

- This can be represented as the sample points of a 2D function of the view angle and roughness value, and can be stored in a 2D image.

- With a sampler configured for linear interpolation, we can read a value for any roughness and view angle.

-

We will preintegrate the term for many roughness values and store the result in a mipmapped cube image.

- We generate random half vectors with Hammersley sets and the cone formula.

- We plug these half vectors into the sum of the term and calculate the integral for many view directions and roughness values. We remove view dependence and assume that the view direction and the normal point the same way, so this can be interpreted as a function of a direction vector and a roughness value.

- We integrate the radiance coming from the skydome.

- This can be stored in a mipmapped cube image. For the same roughness value the integral for every direction can be stored in the same mipmap level. For increasing roughness the integral will be more blurry and can be stored in lower resolution mip levels.

- With a sampler configured for linear interpolation, we can read a value for any roughness and view direction. intermediate roughness values will be interpolated between mip levels.

- During rendering we will read the and term for a given view direction, roughness and normal vector, and calculate the indirect illumination based on these partial results.

Now we can start coding.

General purpose GPU computing

In our triangle tutorial we familiarized ourselves with the graphics pipeline that contains a series of fixed function and programmable steps to process geometry and get it onto the screen. Since this process requires running programs for massive amounts of data, it is backed by hardware which contains hundreds or thousands of programmable processing units and task specific fixed function hardware. People started to take advantage of this hardware for non "vertex processing - rasterization - fragment processing" types of work, such as machine learning and numerical analysis and it proved suitable, giving rise to GPGPU. All of this is good news, because so far we have formulated a kind of work that involves numerical analysis and we may have hope that we can run it on the GPU.

In the old days such work was done using the graphics pipeline by for instance, drawing a full screen quad and performing general purpose computation in the fragment shader and storing the results in a render target for later readback.

Nowadays graphics hardware and graphics APIs offer specialized functions for GPGPU called Compute shaders.

In this talk (with timestamp) Lou Kramer compares using the graphics pipeline for image downscaling and using compute shaders.

Compute shaders

In Vulkan compute shaders are shaders that follow a different model than the "vertex processing - rasterization - fragment processing" model of the graphics pipeline. It does not have attributes, vertex output parameters, etc. Instead when a compute shader is launched, every shader invocation gets an id, and can read and write buffers and textures bound using descriptor sets. Based on the invocation id, every invocation can read and write a specific subset of the bound buffers and images.

An adjusted version of an example compute shader stolen from learnopengl.com can be seen below.

#version 460 core

layout (local_size_x = 1, local_size_y = 1, local_size_z = 1) in;

layout (rgba32f, set = 0, binding = 0) uniform image2D imgOutput;

void main() {

vec4 value = vec4(0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0);

ivec2 texelCoord = ivec2(gl_GlobalInvocationID.xy);

value.x = float(texelCoord.x)/(gl_NumWorkGroups.x);

value.y = float(texelCoord.y)/(gl_NumWorkGroups.y);

imageStore(imgOutput, texelCoord, value);

}

As you can see, there are no attribute variables, no interpolated values, no color attachments, only uniform variables

backed by descriptors. Some types of resources bound by a descriptor set can be written by a shader, and in the given

example, the invocation id stored in the gl_GlobalInvocationID can be used to address parts of the resource

you want to write to.

The programmable processing units of a GPU are arranged in larger units containing registers, ALU, cache, and other hardware. On AMD GCN these unit are called Compute Units, on NVidia hardware they are called Streaming Multiprocessors. These units are capable of executing multiple shader invocations in parallel. Groups of invocations scheduled to the same unit have opportunity to communicate efficiently, and the programming model of Compute Shaders expresses this with workgroups.

Workgroups are groups of invocations within a compute shader dispatch that are scheduled onto the same compute unit/streaming multiprocessor. They can share data in shared memory and in other advanced ways.

A well written compute shader will run many threads within a work group. In the example shader above, which is not a well

written compute shader, this can be seen at the line

layout (local_size_x = 1, local_size_y = 1, local_size_z = 1) in;. The size of a work group is defined by

the variables local_size_x, local_size_y and local_size_z, which are kind of the

3D dimensions of the workgroup thread count. If you multiply them together, you get the amount of threads within a work

group, which in this case will be 1. Running one thread per threadgroup is terrible for hardware utilization, and we will

not do this, but it seems it can still serve as a shader example.

The compute shader defines how many threads will be in a work group, and our application will record compute dispatch

commandy in a command buffer that will specify how many work groups to launch, and this is also specified with three

integers serving as kind of 3D parameters for the workgroup count analogously to the workgroup thread count. Then based

on the workgroup count and the workgroup's thread count there will be vector identifiers available from the shader like

gl_GlobalInvocationID, which can be used to identify every running thread in a compute dispatch and can be

used to identify parts of the resources the shader reads or writes. These identifiers are vectors, and their values are

dependent on the local size dimensions and the compute dispatch dimensions. You'll see examples as you write more

complicated shaders in this tutorial.

This summary of high level concepts of compute shaders are enough. Let's deepen our knowledge by implementing the LD and DFG preintegration using compute shaders.

Writing compute shaders

Now that we wrapped our head around the necessary concepts, it's time to write compute shaders. Let's create a directory

for it called compute_shaders in our shader_src directory!

┣━ Cargo.toml

┣━ build_tools

┣━ shader_src

┃ ┣━ compute_shaders

┃ ┣━ vertex_shaders

┃ ┗━ fragment_shaders

┣━ vk_bindings

┃ ┣━ Cargo.toml

┃ ┣━ build.rs

┃ ┗━ src

┃ ┗━ lib.rs

┗━ vk_tutorial

┣━ Cargo.toml

┗━ src

┗━ main.rs

We are going to write two compute shaders: one for the LD preintegration and one for the DFG preintegration.

Both shaders will use the Van der Corput inverse GLSL implementation stolen from

learnopengl. (There the function name is

RadicalInverse_VdC)

float van_der_corput_inverse(uint bits)

{

bits = (bits << 16u) | (bits >> 16u);

bits = ((bits & 0x55555555u) << 1u) | ((bits & 0xAAAAAAAAu) >> 1u);

bits = ((bits & 0x33333333u) << 2u) | ((bits & 0xCCCCCCCCu) >> 2u);

bits = ((bits & 0x0F0F0F0Fu) << 4u) | ((bits & 0xF0F0F0F0u) >> 4u);

bits = ((bits & 0x00FF00FFu) << 8u) | ((bits & 0xFF00FF00u) >> 8u);

return float(bits) * 2.3283064365386963e-10; // / 0x100000000

}

Writing the LD preintegration shader

Let's start writing the LD preintegration shader! For every pixel of a given mip level we want to determine the corresponding view direction and roughness. Then for the given radiance cubemap (in this case the skydome) we want to plug this view direction, roughness and radiance cubemap into the LD preintegration formula, execute it and store the result in the corresponding pixel within the mip level.

#version 460

layout(local_size_x = 8, local_size_y = 8) in;

const uint ENV_MAP_MAX_MIP_LVL_COUNT = 8;

layout(set = 0, binding = 0) uniform samplerCube input_image;

layout(set = 0, binding = 1, rgba32f) writeonly uniform imageCube output_image[ENV_MAP_MAX_MIP_LVL_COUNT];

layout(push_constant) uniform MipLevel {

uint mip_level;

float roughness;

} push_const_data;

vec3 pos_x_pos_y_pos_z = vec3(1.0, 1.0, 1.0);

vec3 pos_x_pos_y_neg_z = vec3(1.0, 1.0, -1.0);

vec3 pos_x_neg_y_pos_z = vec3(1.0, -1.0, 1.0);

vec3 pos_x_neg_y_neg_z = vec3(1.0, -1.0, -1.0);

vec3 neg_x_pos_y_pos_z = vec3(-1.0, 1.0, 1.0);

vec3 neg_x_pos_y_neg_z = vec3(-1.0, 1.0, -1.0);

vec3 neg_x_neg_y_pos_z = vec3(-1.0, -1.0, 1.0);

vec3 neg_x_neg_y_neg_z = vec3(-1.0, -1.0, -1.0);

vec3 cube_vecs[6][4] = {

// Pos X

{

pos_x_pos_y_pos_z,

pos_x_pos_y_neg_z,

pos_x_neg_y_pos_z,

pos_x_neg_y_neg_z

},

// Neg X

{

neg_x_pos_y_neg_z,

neg_x_pos_y_pos_z,

neg_x_neg_y_neg_z,

neg_x_neg_y_pos_z

},

// Pos Y

{

neg_x_pos_y_neg_z,

pos_x_pos_y_neg_z,

neg_x_pos_y_pos_z,

pos_x_pos_y_pos_z

},

// Neg Y

{

neg_x_neg_y_pos_z,

pos_x_neg_y_pos_z,

neg_x_neg_y_neg_z,

pos_x_neg_y_neg_z

},

// Pos Z

{

neg_x_pos_y_pos_z,

pos_x_pos_y_pos_z,

neg_x_neg_y_pos_z,

pos_x_neg_y_pos_z

},

// Neg Z

{

pos_x_pos_y_neg_z,

neg_x_pos_y_neg_z,

pos_x_neg_y_neg_z,

neg_x_neg_y_neg_z

}

};

vec3 lerp_cube_face(vec3 positions[4], ivec2 texcoord, ivec2 image_size)

{

float x = float(texcoord.x)/float(image_size.x - 1);

float y = float(texcoord.y)/float(image_size.y - 1);

vec3 positions1 = mix(positions[0], positions[1], x);

vec3 positions2 = mix(positions[2], positions[3], x);

return mix(positions1, positions2, y);

}

// Common

float PI = 3.14159265;

float van_der_corput_inverse(uint bits)

{

bits = (bits << 16u) | (bits >> 16u);

bits = ((bits & 0x55555555u) << 1u) | ((bits & 0xAAAAAAAAu) >> 1u);

bits = ((bits & 0x33333333u) << 2u) | ((bits & 0xCCCCCCCCu) >> 2u);

bits = ((bits & 0x0F0F0F0Fu) << 4u) | ((bits & 0xF0F0F0F0u) >> 4u);

bits = ((bits & 0x00FF00FFu) << 8u) | ((bits & 0xFF00FF00u) >> 8u);

return float(bits) * 2.3283064365386963e-10; // / 0x100000000

}

vec2 hammersley(uint i, uint N)

{

return vec2(float(i)/float(N), van_der_corput_inverse(i));

}

vec3 importance_sample_ggx(vec2 sample_vec, float roughness, vec3 normal)

{

float a = roughness * roughness;

float phi = 2.0 * PI * sample_vec.x;

float cos_theta = sqrt((1.0 - sample_vec.y) / (1.0 + (a*a - 1.0) * sample_vec.y));

float sin_theta = sqrt(1.0 - cos_theta * cos_theta);

vec3 half_vec_local = vec3(

sin_theta * cos(phi),

sin_theta * sin(phi),

cos_theta

);

vec3 up = abs(normal.z) < 0.999 ? vec3(0.0, 0.0, 1.0) : vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0);

vec3 tangent_x = normalize(cross(up, normal));

vec3 tangent_y = cross(normal, tangent_x);

return half_vec_local.x * tangent_x + half_vec_local.y * tangent_y + half_vec_local.z * normal;

}

void main()

{

// Texture params

ivec2 texcoord = ivec2(gl_GlobalInvocationID.xy);

ivec2 image_size = ivec2(imageSize(output_image[push_const_data.mip_level]).xy);

ivec3 texcoord_cube = ivec3(texcoord, gl_GlobalInvocationID.z);

vec3 normal = lerp_cube_face(cube_vecs[gl_GlobalInvocationID.z], texcoord, image_size);

vec3 view_vector = normal;

// Environment map preinteg

const uint SAMPLE_COUNT = 1024;

vec3 acc_env = vec3(0.0, 0.0, 0.0);

float acc_env_weight = 0.0;

for(int i=0;i < SAMPLE_COUNT; i++)

{

vec2 sample_vec = hammersley(i, SAMPLE_COUNT);

vec3 half_vector = importance_sample_ggx(sample_vec, push_const_data.roughness, normal);

vec3 light_dir = reflect(-view_vector, half_vector);

float normal_dot_light = min(1.0, dot(normal, light_dir));

if(normal_dot_light > 0.0)

{

acc_env += texture(input_image, light_dir).rgb * normal_dot_light;

acc_env_weight += normal_dot_light;

}

}

vec3 final_env = acc_env / acc_env_weight;

vec4 result = vec4(final_env, 1.0);

imageStore(output_image[push_const_data.mip_level], texcoord_cube, result);

}

Let's start with the first important line of the compute shader,

layout(local_size_x = 8, local_size_y = 8) in;, which defines the size of the compute shader work group.

Using threads will fill even a GCN Wavefront,

which can contain 64 threads. For this shader I see no point in increasing it any further. This will be ineffective

for the mip levels that are lower resolution than 8x8 but the results will be correct and I will go with simplicity.

You can write a specialized solution for those cases as a homework.

Then let's talk about the bound resources. The varibale input_image is a simple sampled cube image,

the same one that we used in the skydome shader. The important one will be the output_image, which is

not a sampled image. It is a storage image array that performs no interpolation, and its data is identified by integers.

Beyond being a storage image it is also a cube image, and the corresponding type is imageCube.

Notice how we need to specify its format in the layout qualifier as rgba32f and specify that it is write

only using writeonly.

A storage image like this can only refer to a single mip level, and we have more than one, so we turn it into an array,

which will be backed by a descriptor array just like our textures were. Every array element will refer to a mip level.

Finally we create push constant to specify the mip level written by the current shader dispatch and the corresponding

roughness parameter. For this we have the fields mip_level and roughness.

Let's jump to the main function and let's discover the rest of the code from there.

We have a gl_GlobalInvocationID variable giving the current invocation a multidimensional identifier. We

turn this into an identifier thad determines a pixel in the cubemap. The first two component will be used as the pixel

coordinate within a slice, and we store it in the variable texcoord. The third component will be the slice

id determining what face of the cubemap will we write to. We create the variable texcoord_cube as a

convenience that stores all of these parameters. We also store the size of a cubemap slice in the variable

image_size.

Then we determine the normal (and view and reflection vector) corresponding to the cubemap pixel we are currently

processing. We store the vertices of every cubemap image plane in the array cube_vecs. We select the one

that belongs to the current cubemap layer based on the third component of the gl_GlobalInvocationID. Then

we interpolate these vertices based on the texcoord variable in the function lerp_cube_face.

Inside that function we normalize the value of texcoord based on the image dimensions, and use it to lerp

between the four corners of the cube face, using the x component in one direction, and then the y component the other

direction. This will serve as the normal vector, and also due to the removed view dependency as the view vector and the

reflection vector pointing towards the mirror direction.

Then we begin performing the Monte Carlo integration. We iterate over every sample point in a for loop.

For every index we generate the corresponding element of the Hammersley set using the hammersley function.

The first component will be the index divided by the sample count, and the other one will be the Van der Corput inverse

of the index.

Then using the importance_sample_ggx we will generate 3D sample directions inside a cone, and make it more

spread out based on the roughness. Then we transform it into the normal vector's local coordinate system. The exact

formula was already introduced at the beginning.

Finally we use this sample direction as half vector. We use the GLSL function reflect to calculate the

corresponding mirror direction and use it as the light direction. Then we sample the cubemap with this light direction,

and accumulate it in a variable outside the loop, using the dot product of the normal vector and the light direction as

weight. We also accumulate this weight as well.

After the for loop we divide the accumulated incoming radiance with the accumulated weights and store it inside the

cubemap pixel identified by the variable texcoord_cube.

I saved this file as 00_env_preinteg.comp in the newly created compute_shaders directory.

We can compile it.

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/00_env_preinteg.comp.spv ./shader_src/compute_shaders/00_env_preinteg.comp

Now it's time for our DFG preintegration!

Writing the DFG integral

The DFG preintegration will use much of the same code as the LD preintegration. The compute shader is the following.

#version 460

layout(local_size_x = 8, local_size_y = 8) in;

layout(set = 0, binding = 0, rg8) writeonly uniform image2D output_image;

float smith_lambda(float roughness, float cos_angle)

{

float cos_sqr = cos_angle * cos_angle;

float tan_sqr = (1.0 - cos_sqr)/cos_sqr;

return (-1.0 + sqrt(1 + roughness * roughness * tan_sqr)) / 2.0;

}

// Common

float PI = 3.14159265;

float van_der_corput_inverse(uint bits)

{

bits = (bits << 16u) | (bits >> 16u);

bits = ((bits & 0x55555555u) << 1u) | ((bits & 0xAAAAAAAAu) >> 1u);

bits = ((bits & 0x33333333u) << 2u) | ((bits & 0xCCCCCCCCu) >> 2u);

bits = ((bits & 0x0F0F0F0Fu) << 4u) | ((bits & 0xF0F0F0F0u) >> 4u);

bits = ((bits & 0x00FF00FFu) << 8u) | ((bits & 0xFF00FF00u) >> 8u);

return float(bits) * 2.3283064365386963e-10; // / 0x100000000

}

vec2 hammersley(uint i, uint N)

{

return vec2(float(i)/float(N), van_der_corput_inverse(i));

}

vec3 importance_sample_ggx(vec2 sample_vec, float roughness, vec3 normal)

{

float a = roughness * roughness;

float phi = 2.0 * PI * sample_vec.x;

float cos_theta = sqrt((1.0 - sample_vec.y) / (1.0 + (a*a - 1.0) * sample_vec.y));

float sin_theta = sqrt(1.0 - cos_theta * cos_theta);

vec3 half_vec_local = vec3(

sin_theta * cos(phi),

sin_theta * sin(phi),

cos_theta

);

vec3 up = abs(normal.z) < 0.999 ? vec3(0.0, 0.0, 1.0) : vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0);

vec3 tangent_x = normalize(cross(up, normal));

vec3 tangent_y = cross(normal, tangent_x);

return half_vec_local.x * tangent_x + half_vec_local.y * tangent_y + half_vec_local.z * normal;

}

void main()

{

ivec2 texcoord = ivec2(gl_GlobalInvocationID.xy);

ivec2 image_size = imageSize(output_image);

// Create parameters

float roughness = max(1e-1, float(texcoord.x) / float(image_size.x - 1));

float camera_dot_normal = max(1e-2, float(texcoord.y) / float(image_size.y - 1));

vec3 normal = vec3(0.0, 0.0, 1.0);

vec3 view_vector = vec3(sqrt(1.0 - camera_dot_normal * camera_dot_normal), 0.0, camera_dot_normal);

// Dfg preinteg

const uint SAMPLE_COUNT = 1024;

vec2 acc = vec2(0.0, 0.0);

for(int i=0;i < SAMPLE_COUNT; i++)

{

vec2 sample_vec = hammersley(i, SAMPLE_COUNT);

vec3 half_vector = importance_sample_ggx(sample_vec, roughness, normal);

vec3 light_dir = reflect(-view_vector, half_vector);

float light_dot_normal = max(0.0, min(1.0, dot(light_dir, normal)));

float light_dot_half = max(0.0, min(1.0, light_dir.z));

float normal_dot_half = max(0.0, min(1.0, half_vector.z));

float view_dot_half = max(0.0, min(1.0, dot(view_vector, half_vector)));

if(light_dot_half > 0.0)

{

float G = step(0.0, view_dot_half) * step(0.0, light_dot_half) / (1.0 + smith_lambda(roughness, camera_dot_normal) + smith_lambda(roughness, light_dot_normal));

float G_vis = view_dot_half * G / (normal_dot_half * camera_dot_normal);

float Fc = pow(max(0.0, 1.0 - view_dot_half), 5);

acc.x += (1.0 - Fc) * G_vis;

acc.y += Fc * G_vis;

}

}

acc = acc / float(SAMPLE_COUNT);

vec4 result = vec4(acc, 0.0, 1.0);

imageStore(output_image, texcoord, result);

}

Looking at the layout(local_size_x = 8, local_size_y = 8) in; at the beginning we can see that this shader

also consists of workgroups of 64 threads, just like the LD preintegration. The first difference can be seen on the

resources being used. The DFG term can be represented as a 2D function, so the storage image output_image

is an image2D.

Let's jump to the main function! We derive the destination pixel's coordinates from the gl_GlobalInvocationID

again store it in the variable texcoord, and query the image dimensions. Then if we represent the DFG term as

a 2D function with the roughness and the dot product of the view vector and the normal vector as parameters, we also need

the roughness and the dot product belonging to the current pixel. Since both values fall within the range of

, normalizing the pixel coordinates with the image

dimensions will theoretically suffice. In practice the lower bound for roughness had to be 1e-1 and the

lower bound of the dot product had to be 1e-2, because it lead to GPU dependent artifacts.

Now that we have the input parameters we can start the integration. First we choose the normal vector to point in the direction of the Z axis. Then we choose a view vector in the XZ plane based on the cosine between the normal vector and the view vector. The Z component can be the cosine and the X component will be the sine, which we get using the Pythagorean theorem.

Now we can start the Monte Carlo integral, calculating the DFG term for every sample point and aggregating them.

Calculating the half vector and the light direction is done the same way as we did with the LD term. Then we calculate

all of the dot products the DFG term depends on and calculate the DFG term. The DFG term had two partial results, the

G_vis involving the geometric attenuation, for which we used the Smith visibility function, and the

Fc involving the Fresnel equation. For the Smith visibility function we pull in the Smith lambda and the

visibility function itself. We evaluate it and multiply and divide it with the right dot products, see the formula

at the introduction. Then we evaluate the partial result of the Fresnel equation as well, see the formula at the

introduction. Then we evaluate the formulae inside the two sums and add them to the accumulator variables.

After the loop we divide the accumulator with the sample count and store the result in the output_image

at the pixel location texcoord.

I saved this file as 01_dfg_preinteg.comp.

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/01_dfg_preinteg.comp.spv ./shader_src/compute_shaders/01_dfg_preinteg.comp

Now it's time to start writing our application.

Checking max workgroup invocations

The local size of both the LD and DFG preintegration shader is 8x8 = 64. Our application can only run on GPUs that support at least this many invocations per workgroup. Actually GPUs supporting at least 128 invocations per workgroup is guaranteed, but for shaders with larger workgroup local sizes, you want to check support like this:

//

// Checking physical device capabilities

//

// Getting physical device properties

let mut phys_device_properties = VkPhysicalDeviceProperties::default();

// ...

// Checking physical device limits

// This one is actually unnecessary, because the minimum will always be at least 128,

// but for larger workgroups you may want to check this.

if phys_device_properties.limits.maxComputeWorkGroupInvocations < 64

{

panic!("maxComputeWorkGroupInvocations must be at least 64. Actual value: {:?}", phys_device_properties.limits.maxComputeWorkGroupInvocations);

}

Among the device limits the field maxComputeWorkGroupInvocations holds the upper bound to invocation count

in a workgroup. Now that we know our GPU is capable of running the preintegration shaders, let's load them into shader

modules!

Loading compute shaders

We have two compiled shaders, one for the LD and one for the DFG preintegration. Let's load them!

Loading LD preintegration shader

Let's load the LD preintegration shader like any other shader!

//

// Shader modules

//

// ...

// Environment preinteg shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/00_env_preinteg.comp.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

let mut bytecode = Vec::new();

file.read_to_end(&mut bytecode).expect("Failed to read shader source");

let shader_module_create_info = VkShaderModuleCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_SHADER_MODULE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

codeSize: bytecode.len(),

pCode: bytecode.as_ptr() as *const u32

};

println!("Creating env preinteg shader module.");

let mut env_preinteg_shader_module = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateShaderModule(

device,

&shader_module_create_info,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut env_preinteg_shader_module

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create env preinteg shader. Error: {}.", result);

}

Also let's not forget to clean up!

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting env preinteg shader module");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyShaderModule(

device,

env_preinteg_shader_module,

std::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

Loading DFG preintegration shader

Now we load the DFG preintegration shader.

//

// Shader modules

//

// ...

// Dfg preinteg shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/01_dfg_preinteg.comp.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

let mut bytecode = Vec::new();

file.read_to_end(&mut bytecode).expect("Failed to read shader source");

let shader_module_create_info = VkShaderModuleCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_SHADER_MODULE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

codeSize: bytecode.len(),

pCode: bytecode.as_ptr() as *const u32

};

println!("Creating dfg preinteg shader module.");

let mut dfg_preinteg_shader_module = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateShaderModule(

device,

&shader_module_create_info,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut dfg_preinteg_shader_module

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create dfg preinteg shader. Error: {}.", result);

}

We also clean it up.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting dfg preinteg shader module");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyShaderModule(

device,

dfg_preinteg_shader_module,

std::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

Descriptor set layout

Compute shaders can read and write buffers and images. The LD preintegration shader reads from a sampled cube image and writes to cube image mip layers, and the DFG preintegration shader writes to a 2D image. These must be bound by a descriptor set, just like when we use a graphics pipeline.

LD preintegration descriptor set layout

We need to sample the skydome cube image and we need to write to cube image mip layers. We already know how to bind a sampled cube image from the previous chapter. As for the destination image, these are represented by a different descriptor type, and in the compute shader we used a uniform array to hold every mip level, and these are backed by a descriptor array.

//

// Descriptor set layout

//

// ...

// Environment map preintegration

const MAX_ENV_MIP_LVL_COUNT: usize = 8;

let compute_layout_bindings = [

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding {

binding: 0,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER,

descriptorCount: 1,

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_COMPUTE_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

pImmutableSamplers: std::ptr::null()

},

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding {

binding: 1,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_STORAGE_IMAGE,

descriptorCount: MAX_ENV_MIP_LVL_COUNT as u32,

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_COMPUTE_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

pImmutableSamplers: std::ptr::null()

}

];

let descriptor_set_layout_create_info = VkDescriptorSetLayoutCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_DESCRIPTOR_SET_LAYOUT_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

bindingCount: compute_layout_bindings.len() as u32,

pBindings: compute_layout_bindings.as_ptr()

};

println!("Creating env preinteg descriptor set layout.");

let mut env_preinteg_descriptor_set_layout = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateDescriptorSetLayout(

device,

&descriptor_set_layout_create_info,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut env_preinteg_descriptor_set_layout

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create env preinteg descriptor set layout. Error: {}.", result);

}

The skydome image will be referred to by a single VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER at binding

0. The storage images on the other hand will be represented by a new descriptor type,

VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_STORAGE_IMAGE. We will create environment cube images with

MAX_ENV_MIP_LVL_COUNT mip levels, which will be 8, so we will need at least this many

descriptors in the descriptor array.

We pass this to the create function and we have the descriptor set layout.

At the end we clean up the new descriptor set layout.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting env preinteg descriptor set layout");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyDescriptorSetLayout(

device,

env_preinteg_descriptor_set_layout,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

DFG preintegration descriptor set layout

The DFG preintegration will write to a single 2D image. Here are the bindings for it:

//

// Descriptor set layout

//

// ...

// Dfg preintegration

let compute_layout_bindings = [

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding {

binding: 0,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_STORAGE_IMAGE,

descriptorCount: 1,

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_COMPUTE_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

pImmutableSamplers: std::ptr::null()

}

];

let descriptor_set_layout_create_info = VkDescriptorSetLayoutCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_DESCRIPTOR_SET_LAYOUT_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

bindingCount: compute_layout_bindings.len() as u32,

pBindings: compute_layout_bindings.as_ptr()

};

println!("Creating dfg preinteg descriptor set layout.");

let mut dfg_preinteg_descriptor_set_layout = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateDescriptorSetLayout(

device,

&descriptor_set_layout_create_info,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut dfg_preinteg_descriptor_set_layout

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create dfg preinteg descriptor set layout. Error: {}.", result);

}

This one can be represented by a single VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_STORAGE_IMAGE descriptor at binding

0.

At the end we clean this one up as well.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting dfg preinteg descriptor set layout");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyDescriptorSetLayout(

device,

dfg_preinteg_descriptor_set_layout,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

Pipeline layout

Like vertex and fragment shaders, compute shaders can access buffers and images bound by descriptor sets and they have push constant data as well. Like graphics pipelnies, compute pipelines specify their descriptor sets and push constants with pipeline layouts. Here we create pipeline layouts for our LD and DFG preintegration pipeline layouts.

LD preintegration pipeline layout

First we create the LD preinteg pipeline layout. The shader expects a descriptor set layout for the source cube image and the destination cube mip levels, and a push constant region backing the currently written mip level and the corresponding roughness value.

//

// Pipeline layout

//

// ...

// Environment preintegration

let descriptor_set_layouts = [

env_preinteg_descriptor_set_layout

];

// Mip level + roughness

let env_compute_push_constant_size = (std::mem::size_of::<u32>() + std::mem::size_of::<f32>()) as u32;

let push_constant_ranges = [

VkPushConstantRange {

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_COMPUTE_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

offset: 0,

size: env_compute_push_constant_size

}

];

let compute_pipeline_layout_create_info = VkPipelineLayoutCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_LAYOUT_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

setLayoutCount: descriptor_set_layouts.len() as u32,

pSetLayouts: descriptor_set_layouts.as_ptr(),

pushConstantRangeCount: push_constant_ranges.len() as u32,

pPushConstantRanges: push_constant_ranges.as_ptr()

};

println!("Creating env preinteg pipeline layout.");

let mut env_compute_pipeline_layout = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreatePipelineLayout(

device,

&compute_pipeline_layout_create_info,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut env_compute_pipeline_layout

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create env preinteg pipeline layout. Error: {}.", result);

}

The descriptor_set_layouts array contains a single descriptor set layout, the

env_preinteg_descriptor_set_layout. The push constant range for the compute shader will have the

stageFlags set to VK_SHADER_STAGE_COMPUTE_BIT, the offset will be 0

and the size will be std::mem::size_of::<u32>() + std::mem::size_of::<f32>(), making room for

a 32 bit mip level index and a 32 bit float roughness value.

At the end of the program we clean it up.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting env preinteg pipeline layout");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyPipelineLayout(

device,

env_compute_pipeline_layout,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

Now we can create the DFG pipeline layout.

DFG preintegration pipeline layout

The DFG pipeline layout will be a bit simpler, because it only takes an output image descriptor bound by a descriptor set.

//

// Pipeline layout

//

// ...

// Dfg preintegration

let descriptor_set_layouts = [

dfg_preinteg_descriptor_set_layout

];

let compute_pipeline_layout_create_info = VkPipelineLayoutCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_LAYOUT_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

setLayoutCount: descriptor_set_layouts.len() as u32,

pSetLayouts: descriptor_set_layouts.as_ptr(),

pushConstantRangeCount: 0,

pPushConstantRanges: std::ptr::null_mut()

};

println!("Creating dfg preinteg pipeline layout.");

let mut dfg_compute_pipeline_layout = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreatePipelineLayout(

device,

&compute_pipeline_layout_create_info,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut dfg_compute_pipeline_layout

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create dfg preinteg pipeline layout. Error: {}.", result);

}

The descriptor_set_layouts array contains the dfg_preinteg_descriptor_set_layout and nothing

else is needed, creation is simple.

At the end of the program we clean this up as well.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting dfg preinteg pipeline layout");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyPipelineLayout(

device,

dfg_compute_pipeline_layout,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

Compute pipelines

Compute shaders are bound using a Vulkan pipeline. In the hardcoded triangle chapter we defined pipelines generally, mentioning that there are special kinds of pipelines such as graphics pipelines.

Compute pipelines - like graphics pipelines - are special pipelines as well, but this one does not have fixed function pipeline steps, only a shader, the compute shader, and a pipeline layout, so it is much simpler and easier to create. Below we create both the LD and the DFG preintegration pipelines.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

// Compute pipelines

let compute_pipeline_create_infos = [

VkComputePipelineCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_COMPUTE_PIPELINE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

stage: VkPipelineShaderStageCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_SHADER_STAGE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

pSpecializationInfo: std::ptr::null(),

stage: VK_SHADER_STAGE_COMPUTE_BIT,

module: env_preinteg_shader_module,

pName: b"main\0".as_ptr() as *const i8

},

layout: env_compute_pipeline_layout,

basePipelineHandle: std::ptr::null_mut(),

basePipelineIndex: -1

},

VkComputePipelineCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_COMPUTE_PIPELINE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

stage: VkPipelineShaderStageCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_SHADER_STAGE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

pSpecializationInfo: std::ptr::null(),

stage: VK_SHADER_STAGE_COMPUTE_BIT,

module: dfg_preinteg_shader_module,

pName: b"main\0".as_ptr() as *const i8

},

layout: dfg_compute_pipeline_layout,

basePipelineHandle: std::ptr::null_mut(),

basePipelineIndex: -1

}

];

println!("Creating compute pipelines.");

let mut compute_pipelines = [std::ptr::null_mut(); 2];

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateComputePipelines(

device,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

compute_pipeline_create_infos.len() as u32,

compute_pipeline_create_infos.as_ptr(),

std::ptr::null_mut(),

compute_pipelines.as_mut_ptr()

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create compute pipelines. Error: {}.", result);

}

let env_compute_pipeline = compute_pipelines[0];

let dfg_compute_pipeline = compute_pipelines[1];

A compute pipeline's parameters are specified by a VkComputePipelineCreateInfo struct. The important fields

that we fill with useful data are the stage and layout.

The stage field is a VkPipelineShaderStageCreateInfo struct, which is filled the same way as it

was for the graphics pipelines, just the stage field is set to VK_SHADER_STAGE_COMPUTE_BIT.

The layout field is a pointer to the pipeline layout for the compute pipeline.

Just like graphics pipelines, compute pipelines can be bulk created. They are created with a call to

vkCreateComputePipelines, which can take an array of VkComputePipelineCreateInfo and write the

new pipelines to a VkPipeline array. The first element of the pipeline create info array is the LD

preintegration pipeline, having its shader module set to env_preinteg_shader_module and its pipeline layout

set to env_compute_pipeline_layout. The second element is for the DFG preintegration pipeline, analogously

its shader module set to dfg_preinteg_shader_module and its pipeline layout set to

dfg_compute_pipeline_layout. The created pipelines are written to compute_pipelines, and then

its elements are assigned to env_compute_pipeline and dfg_compute_pipeline.

These pipelines need to be cleaned up at the end of the program.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting dfg preinteg pipeline");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyPipeline(

device,

dfg_compute_pipeline,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

println!("Deleting env preinteg pipeline");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyPipeline(

device,

env_compute_pipeline,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

Since the newly created compute pipelines are different kinds of pipelines than the already existing graphics pipelines, we should add just one comment for code organization purposes to separate them.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// Graphics pipelines

// ...

There. Before graphics pipeline creation we prepended a comment.

Also since our compute pipelines are differentiated in name, let's rename our graphics pipeline array as well just for clarity. It won't affect behavior.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

println!("Creating graphics pipelines.");

let mut graphics_pipelines = [std::ptr::null_mut(); 2];

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateGraphicsPipelines(

device,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

pipeline_create_infos.len() as u32,

pipeline_create_infos.as_ptr(),

core::ptr::null_mut(),

graphics_pipelines.as_mut_ptr()

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create graphics pipelines. Error: {}", result);

}

let model_pipeline = graphics_pipelines[0];

let skydome_pipeline = graphics_pipelines[1];

Now we need to create the DFG and LD images.

Image creation

Now it's time to create our DFG image and our LD preintegrated environment map.

Let's start with preparing our metadata! We need a width, a height and a format. Since for previous images we have that

in the Image data and Cube data parts in the code, we add them there.

First let's add the DFG image metadata!

//

// Image data

//

// ...

let dfg_img_width = 128;

let dfg_img_height = 128;

let dfg_image_format = VK_FORMAT_R8G8_UNORM;

I chose the DFG image resolution to be 128x128.

The part that is out of the ordinary is the format VK_FORMAT_R8G8_UNORM. It only has two color component.

Since for every pixel we store only two partial result, there is no point in a format that has more color channels.

Then let's add the environment map metadata!

//

// Cube data

//

let env_img_width = 128;

let env_img_height = 128;

I chose the environment image resolution to be 128x128 as well. For the format we'll just reuse our

cube_image_format variable, because it would be just float RGBA anyway, unlike the DFG, which is only two

component. This format served us for the skydome for storing radiance, so we'll go with it.

DFG image

Now we start creating the DFG image. The creation is the same as any other 2D image.

//

// DFG image

//

let mut format_properties = VkFormatProperties::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetPhysicalDeviceFormatProperties(

chosen_phys_device,

dfg_image_format,

&mut format_properties

);

}

if format_properties.optimalTilingFeatures & VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_SAMPLED_IMAGE_BIT as VkFormatFeatureFlags == 0

{

panic!("Image format VK_FORMAT_R8G8_UNORM with VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL does not support usage flags VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_SAMPLED_IMAGE_BIT.");

}

if format_properties.optimalTilingFeatures & VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_STORAGE_IMAGE_BIT as VkFormatFeatureFlags == 0

{

panic!("Image format VK_FORMAT_R8G8_UNORM with VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL does not support usage flags VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_STORAGE_IMAGE_BIT.");

}

let image_create_info = VkImageCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

imageType: VK_IMAGE_TYPE_2D,

format: dfg_image_format,

extent: VkExtent3D {

width: dfg_img_width as u32,

height: dfg_img_height as u32,

depth: 1

},

mipLevels: 1,

arrayLayers: 1,

samples: VK_SAMPLE_COUNT_1_BIT,

tiling: VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL,

usage: (VK_IMAGE_USAGE_SAMPLED_BIT |

VK_IMAGE_USAGE_STORAGE_BIT) as VkImageUsageFlags,

sharingMode: VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE,

queueFamilyIndexCount: 0,

pQueueFamilyIndices: std::ptr::null(),

initialLayout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_UNDEFINED

};

println!("Creating dfg image.");

let mut dfg_image = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateImage(

device,

&image_create_info,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut dfg_image

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create dfg image. Error: {}", result);

}

let mut mem_requirements = VkMemoryRequirements::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetImageMemoryRequirements(

device,

dfg_image,

&mut mem_requirements

);

}

let type_filter = mem_requirements.memoryTypeBits;

let mut chosen_memory_type = phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount;

for i in 0..phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

if type_filter & (1 << i) != 0 &&

(phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypes[i as usize].propertyFlags & image_mem_props) == image_mem_props

{

chosen_memory_type = i;

break;

}

}

if chosen_memory_type == phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

panic!("Could not find memory type.");

}

let image_alloc_info = VkMemoryAllocateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_MEMORY_ALLOCATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

allocationSize: mem_requirements.size,

memoryTypeIndex: chosen_memory_type

};

println!("Dfg image size: {}", mem_requirements.size);

println!("Dfg image align: {}", mem_requirements.alignment);

println!("Allocating dfg image memory");

let mut dfg_image_memory = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkAllocateMemory(

device,

&image_alloc_info,

std::ptr::null(),

&mut dfg_image_memory

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Could not allocate memory. Error: {}", result);

}

let result = unsafe

{

vkBindImageMemory(

device,

dfg_image,

dfg_image_memory,

0

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to bind memory to dfg image. Error: {}", result);

}

//

// DFG image view

//

let image_view_create_info = VkImageViewCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_VIEW_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

image: dfg_image,

viewType: VK_IMAGE_VIEW_TYPE_2D,

format: dfg_image_format,

components: VkComponentMapping {

r: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

g: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

b: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

a: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY

},

subresourceRange: VkImageSubresourceRange {

aspectMask: VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_COLOR_BIT as VkImageAspectFlags,

baseMipLevel: 0,

levelCount: 1,

baseArrayLayer: 0,

layerCount: 1

}

};

println!("Creating dfg image view.");

let mut dfg_image_view = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateImageView(

device,

&image_view_create_info,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut dfg_image_view

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create image view. Error: {}", result);

}

At the end of the program we clean this up.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting dfg image view");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyImageView(

device,

dfg_image_view,

std::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

println!("Deleting dfg image device memory");

unsafe

{

vkFreeMemory(

device,

dfg_image_memory,

std::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

println!("Deleting dfg image");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyImage(

device,

dfg_image,

std::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

Now let's create our environment maps!

LD environment image

The environment map creation is a bit different than a standard cubemap creation, because this time we create mip levels. Let's remember that the preintegrated environment map for higher roughness values gets blurry, and using lower resolution images saves memory. There is a Vulkan feature for creating an image that does not only create storage for the full resolution image, but progressively downscaled versions as well, and this is mipmapping. If we create a cube image with mipmapping, we can store the high roughness preintegrated environment maps in lower mip levels, and Vulkan can even interpolate between them for roughness values in-between. The image creation code is below.

//

// Environment texture

//

let mut format_properties = VkFormatProperties::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetPhysicalDeviceFormatProperties(

chosen_phys_device,

cube_image_format,

&mut format_properties

);

}

if format_properties.optimalTilingFeatures & VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_SAMPLED_IMAGE_BIT as VkFormatFeatureFlags == 0

{

panic!("Image format VK_FORMAT_R32G32B32A32_SFLOAT with VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL does not support usage flags VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_SAMPLED_IMAGE_BIT.");

}

if format_properties.optimalTilingFeatures & VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_STORAGE_IMAGE_BIT as VkFormatFeatureFlags == 0

{

panic!("Image format VK_FORMAT_R32G32B32A32_SFLOAT with VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL does not support usage flags VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_STORAGE_IMAGE_BIT.");

}

let image_create_info = VkImageCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: VK_IMAGE_CREATE_CUBE_COMPATIBLE_BIT as VkImageCreateFlags,

imageType: VK_IMAGE_TYPE_2D,

format: cube_image_format,

extent: VkExtent3D {

width: env_img_width as u32,

height: env_img_height as u32,

depth: 1

},

mipLevels: MAX_ENV_MIP_LVL_COUNT as u32,

arrayLayers: 6,

samples: VK_SAMPLE_COUNT_1_BIT,

tiling: VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL,

usage: (VK_IMAGE_USAGE_SAMPLED_BIT |

VK_IMAGE_USAGE_STORAGE_BIT) as VkImageUsageFlags,

sharingMode: VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE,

queueFamilyIndexCount: 0,

pQueueFamilyIndices: std::ptr::null(),

initialLayout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_UNDEFINED

};

println!("Creating environment image.");

let mut env_image = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateImage(

device,

&image_create_info,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut env_image

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create environment image. Error: {}", result);

}

let mut mem_requirements = VkMemoryRequirements::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetImageMemoryRequirements(

device,

env_image,

&mut mem_requirements

);

}

let mut chosen_memory_type = phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount;

for i in 0..phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

if type_filter & (1 << i) != 0 &&

(phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypes[i as usize].propertyFlags & image_mem_props) == image_mem_props

{

chosen_memory_type = i;

break;

}

}

if chosen_memory_type == phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

panic!("Could not find memory type.");

}

let image_alloc_info = VkMemoryAllocateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_MEMORY_ALLOCATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

allocationSize: mem_requirements.size,

memoryTypeIndex: chosen_memory_type

};

println!("Environment image size: {}", mem_requirements.size);

println!("Environment image align: {}", mem_requirements.alignment);

println!("Allocating environment image memory");

let mut env_image_memory = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkAllocateMemory(

device,

&image_alloc_info,

std::ptr::null(),

&mut env_image_memory

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Could not allocate memory. Error: {}", result);

}

let result = unsafe

{

vkBindImageMemory(

device,

env_image,

env_image_memory,

0

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to bind memory to environment image. Error: {}", result);

}

//

// Environment image view

//

// Read view

let image_view_create_info = VkImageViewCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_VIEW_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

image: env_image,

viewType: VK_IMAGE_VIEW_TYPE_CUBE,

format: cube_image_format,

components: VkComponentMapping {

r: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

g: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

b: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

a: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY

},

subresourceRange: VkImageSubresourceRange {

aspectMask: VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_COLOR_BIT as VkImageAspectFlags,

baseMipLevel: 0,

levelCount: MAX_ENV_MIP_LVL_COUNT as u32,

baseArrayLayer: 0,

layerCount: 6

}

};

println!("Creating environment image view.");

let mut env_image_view = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateImageView(

device,

&image_view_create_info,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut env_image_view

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create environment image view. Error: {}", result);

}

// ...

This image creation is almost the same as the cube image creation code from before. We take the width, the height and the format, and create six array layers. Allocate memory, bind it and create an image view.

The difference is the creation and usage of mip levels. In the VkImageCreateInfo struct there is a field

mipLevels which is set to MAX_ENV_MIP_LVL_COUNT. For a 128x128 image this will create lower

resolution images as well, such as 64x64, 32x32 and so on. We can store the incoming radiance for high roughness in

these.

The image view that we will use for reading must be adjusted as well. In the VkImageSubresourceRange struct

there is a field levelCount that is now set to MAX_ENV_MIP_LVL_COUNT. Now it represents the

mip levels as well, and shaders can sample from them as well.

Let's remember that the compute shader that we created writes only to a single mip level, and different mip levels are stored in a uniform array. We will back it with a descriptor array, and for that we will need an image view for every mip level.

//

// Environment image view

//

// ...

// Write views

let mut env_image_write_views = [std::ptr::null_mut(); MAX_ENV_MIP_LVL_COUNT];

for i in 0..MAX_ENV_MIP_LVL_COUNT

{

let image_view_create_info = VkImageViewCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_VIEW_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: std::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

image: env_image,

viewType: VK_IMAGE_VIEW_TYPE_CUBE,

format: cube_image_format,

components: VkComponentMapping {

r: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

g: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

b: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

a: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY

},

subresourceRange: VkImageSubresourceRange {

aspectMask: VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_COLOR_BIT as VkImageAspectFlags,

baseMipLevel: i as u32,

levelCount: 1,

baseArrayLayer: 0,

layerCount: 6

}

};

println!("Creating environment image view.");

let mut env_image_write_view = std::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateImageView(

device,

&image_view_create_info,

std::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut env_image_write_view

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create environment image view. Error: {}", result);

}

env_image_write_views[i] = env_image_write_view;

}

We create an array of image views. The mip level is determined by the baseMipLevel and

levelCount fields of the VkImageSubresourceRange. This time the base mip level is the index

in the for loop, and the mip level count is one. The baseArrayLayer is still 0 and the

layerCount is still 6, so it represents every face of the cube image for a given mip level.

This is how we get an image view for every mip level.

At the end of the program let's destroy every image view and the environment map.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

for env_image_write_view in env_image_write_views

{

println!("Deleting environment write image view");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyImageView(

device,

env_image_write_view,

std::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

}

println!("Deleting environment image view");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyImageView(

device,

env_image_view,

std::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

println!("Deleting environment image device memory");

unsafe

{

vkFreeMemory(

device,

env_image_memory,

std::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

println!("Deleting environment image");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyImage(

device,

env_image,

std::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

Compute dispatch

Before the main loop we perform the preintegrations.

The steps we need will be the following:

-

We need to create descriptor sets.

- For the DFG preintegration we need one that binds the DFG texture.

- For the LD preintegration we need one that binds every mip level of our environment map for writing, and the skydome for sampling.

- We need to create a command pool and a command buffer

-

Then we need to record the commands.

-

We need to record the LD preintegration.

- We need to bind the descriptor set for LD preintegration.

- We also need to bind the LD pipeline.

- Then we issue the compute dispatches for every mip level of the environment texture.

-

We need to record the DFG preintegration.

- We need to bind the DFG descriptor set

- We also need to bind the DFG pipeline

- Then we issue the compute dispatch for the DFG preintegration

-

- After command recording we submit the command buffer.

- Finally we clean up.

The logic will be similar to the one we wrote for the transfer command buffer. Let's get started!

//

// Preintegration

//

{

// ...

}