Vertex and Index buffer

In the previous chapter we have familiarized ourselves with the graphics pipeline. We summarized its essential processing stages, some of the basic parameters of those stages, written some very basic shaders and elaborated on the parallel nature of shader execution.

Previously our vertex shader contained a hardcoded triangle. In this chapter we are going to supply the geometry to the vertex shader from memory.

First we are going to understand how memory allocations and memory backed resources work in Vulkan. Then we define our vertex data, create a vertex buffer and upload our vertex data into it.

Next we prepare our pipeline to consume data from vertex buffers, bind the vertex buffers during command recording, and adjust the vertex shader to use data from the vertex buffer instead of the hardcoded vertex data.

After all of this we find ways to make rendering more efficient and learn to use index buffers.

This tutorial is in open beta. There may be bugs in the code and misinformation and inaccuracies in the text. If you find any, feel free to open a ticket on the repo of the code samples.

Removing non dynamic pipeline

First I am going to do a little cleanup. I am going to remove the pipeline which had the viewport and scissor baked in, and use the dynamic pipeline exclusively. Including it as a feature demo made sense in the previous chapter about graphics pipelines, but right now we are learning new API constructs, and it will be nothing but noise, so I simplify the sample application.

Nothing stops you from skipping these steps, just don't forget to take your different setup into consideration when following the rest of the tutorial.

I remove the creation of the non dynamic pipeline. We will only create one single pipeline called

pipeline, its viewport state will not supply viewport and scissor size, its dynamic state

will contain VK_DYNAMIC_STATE_VIEWPORT and VK_DYNAMIC_STATE_SCISSOR, and the

creation of the second pipeline will be removed.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let viewport_state = VkPipelineViewportStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_VIEWPORT_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

viewportCount: 1,

pViewports: core::ptr::null(),

scissorCount: 1,

pScissors: core::ptr::null()

};

// ...

// Dynamic state

let dynamic_state_array = [VK_DYNAMIC_STATE_VIEWPORT, VK_DYNAMIC_STATE_SCISSOR];

let dynamic_state = VkPipelineDynamicStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_DYNAMIC_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

dynamicStateCount: dynamic_state_array.len() as u32,

pDynamicStates: dynamic_state_array.as_ptr(),

};

// Creation

let pipeline_create_info = VkGraphicsPipelineCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_GRAPHICS_PIPELINE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

stageCount: shader_stage_info.len() as u32,

pStages: shader_stage_info.as_ptr(),

pVertexInputState: &vertex_input_state,

pInputAssemblyState: &input_assembly_state,

pTessellationState: core::ptr::null(),

pViewportState: &viewport_state,

pRasterizationState: &rasterization_state,

pMultisampleState: &multisample_state,

pDepthStencilState: core::ptr::null(),

pColorBlendState: &color_blend_state,

pDynamicState: &dynamic_state,

layout: pipeline_layout,

renderPass: render_pass,

subpass: 0,

basePipelineHandle: core::ptr::null_mut(),

basePipelineIndex: -1

};

println!("Creating pipeline.");

let mut pipeline = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateGraphicsPipelines(

device,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

1,

&pipeline_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut pipeline

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create pipeline. Error: {}", result);

}

It will be cleaned up like this.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting pipeline");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyPipeline(

device,

pipeline,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

Then we remove the conditional where we bound the static viewport/scissor pipeline from the command buffer recording.

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

vkCmdBindPipeline(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

VK_PIPELINE_BIND_POINT_GRAPHICS,

pipeline

);

let viewports = [

VkViewport {

x: 0.0,

y: 0.0,

width: width as f32,

height: height as f32,

minDepth: 0.0,

maxDepth: 1.0

}

];

vkCmdSetViewport(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

0,

viewports.len() as u32,

viewports.as_ptr()

);

let scissors = [

VkRect2D {

offset: VkOffset2D {

x: 0,

y: 0

},

extent: VkExtent2D {

width: width,

height: height

}

}

];

vkCmdSetScissor(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

0,

scissors.len() as u32,

scissors.as_ptr()

);

vkCmdDraw(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

3,

1,

0,

0

);

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

Now our code is a bit simpler and lets us focus on learning Vertex and Index buffers.

Buffers

This is where the tutorial really begins.

In the previous tutorial we have created a shader that can render a triangle whose vertices are hardcoded into the shader. Obviously this does not work for a real world application. In a real world application you want to load models from files or generate models procedurally and store them in memory. Later during rendering you want to refer to the memory location of these models. The Vulkan objects we need for this are buffer objects and device memory.

In Vulkan device memory is a Vulkan object representing memory in VRAM or System memory. Vulkan allows you to allocate these memory blocks. You can store data in this memory and the GPU can access it in various ways.

Most of the time when you have to reference memory in Vulkan, you do not reference memory directly but reference memory backed resources. In this sense, memory backed resources are indirections with additional data for interpreting memory.

In Vulkan buffers are memory backed resources representing linear memory.

You can create memory backed resources such as buffers, determine what kind of memory they can reside in, then take an appropriate device memory object and assign a range of it to the memory backed resources.

In the following section we will illustrate memory allocation and buffer creation on vertex buffers.

Vertex buffers

Vertex positions must be stored in buffers in order to be accessible from a vertex shader.

First we are going to hardcode the vertex data into our application. (the executable, not the shader) Then we create a buffer object large enough to contain the vertex data. Then we allocate enough memory to hold the contents of the buffer and assign it to the buffer. Finally we upload our vertex data into the newly allocated memory.

Preparing vertex data

First we define a triangle that we want to render. Let's grab inkscape and let's draw a coordinate system and a triangle into it! Once it's done, we can read the coordinates.

Then we hardcode the coordinates of the vertices into a vector of floats.

//

// Vertex data

//

let vertices: Vec<f32> = vec![

// Triangle

// Vertex 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

1.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, 1.0,

];

Pay attention that we are very explicit about this being a f32 array! We don't want the compiler to

create f64 arrays for us, and let unsafe code misinterpret it as f32! Accidents like

this happened to me in the past.

Buffer creation

Now that the data is available, we can tell how large our buffer needs to be. We need

vertices.len() * std::mem::size_of::<f32>() bytes to store our vertices. Now we can create

our vertex buffer.

In Vulkan vertex buffers are buffers containing vertex data to be read in a vertex shader.

//

// Vertex data

//

// ...

// Vertex buffer size

let vertex_data_size = vertices.len() * core::mem::size_of::<f32>();

//

// Vertex buffer

//

// Create buffer

let vertex_buffer_create_info = VkBufferCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_BUFFER_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

size: vertex_data_size as VkDeviceSize,

usage: VK_BUFFER_USAGE_VERTEX_BUFFER_BIT as VkBufferUsageFlags,

sharingMode: VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE,

queueFamilyIndexCount: 0,

pQueueFamilyIndices: core::ptr::null()

};

println!("Creating vertex buffer.");

let mut vertex_buffer = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateBuffer(

device,

&vertex_buffer_create_info,

core::ptr::null(),

&mut vertex_buffer

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create vertex buffer. Error: {}.", result);

}

First we specified the size of the vertex data, and then filled our VkBufferCreateInfo.

The important fields are size, usage and sharingMode. The rest have zero

assigned to them. The field size will contain the size of the vertex data, the usage is

VK_BUFFER_USAGE_VERTEX_BUFFER_BIT, as we only intend to read vertex data from it and

nothing else, and sharingMode will be VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE, because it will

only be used from the graphics queue.

Let's immediately add the cleanup function!

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting vertex buffer");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyBuffer(

device,

vertex_buffer,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

Then we are going to query what kind of memory can back this buffer.

//

// Vertex buffer

//

// ...

// Create memory

let mut mem_requirements = VkMemoryRequirements::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetBufferMemoryRequirements(

device,

vertex_buffer,

&mut mem_requirements

);

}

The result is stored in a VkMemoryRequirements struct which contains a size, an

alignment and memoryTypeBits.

We will go into details on every one of these as we progress, but first we have to explain one particular

parameter: what is a memory type?

Memory types and heaps

In Vulkan, memory can come from several places. For instance, for a discrete GPU, the memory can be allocated in system memory or in VRAM. System memory can be written by the CPU whereas the VRAM may be faster to access from GPU, but it requires special memory transfer commands to move data into it. (Spoiler: this is what the next chapter will be about.) A limited amount of VRAM may be directly writable from the CPU as well. For an integrated GPU, the only memory where we can allocate is the system memory.

Vulkan expresses these different kinds of memory with memory types and memory heaps.

We can query device memory properties.

//

// Device mem properties

//

let mut phys_device_mem_properties = VkPhysicalDeviceMemoryProperties::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetPhysicalDeviceMemoryProperties(

chosen_phys_device,

&mut phys_device_mem_properties

);

}

In this structure we can see two arrays of structures: memory types and memory heaps.

Memory heaps are regions of memory where we can allocate memory from. For instance, in a discrete GPU there may be three heaps: the system memory, cpu accessible VRAM and non-cpu accessible VRAM. In an integrated GPU there may be a single heap, system memory.

The previously queried structure contains all the heaps and their sizes. You can print out its contents to see what's inside.

println!("Listing memory heaps:");

for i in 0..phys_device_mem_properties.memoryHeapCount as usize

{

let memory_heap = phys_device_mem_properties.memoryHeaps[i];

println!("Memory heap {}", i);

println!("Size: {}", memory_heap.size);

println!(

"Flag VK_MEMORY_HEAP_DEVICE_LOCAL_BIT: {}",

memory_heap.flags & VK_MEMORY_HEAP_DEVICE_LOCAL_BIT as VkMemoryHeapFlags != 0

);

}

Memory types are different capabilities a memory allocation can have. Each memory type is assigned to a heap, and each memory type can have capabilities such as device local, which means the device may access it faster, host visible, which means it can be accessed from CPU, etc.

Memory types allow us to select a range of capabilities for our allocations that come from a specific heap. You can print this one out as well.

println!("Listing memory types:");

for i in 0..phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount as usize

{

let memory_type = phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypes[i];

println!("Memory type {}", i);

println!("Heap: {}", memory_type.heapIndex);

println!(

"Flag VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_DEVICE_LOCAL_BIT: {}",

memory_type.propertyFlags & VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_DEVICE_LOCAL_BIT as VkMemoryPropertyFlags != 0

);

println!(

"Flag VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_VISIBLE_BIT: {}",

memory_type.propertyFlags & VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_VISIBLE_BIT as VkMemoryPropertyFlags != 0

);

println!(

"Flag VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_COHERENT_BIT: {}",

memory_type.propertyFlags & VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_COHERENT_BIT as VkMemoryPropertyFlags != 0

);

println!(

"Flag VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_CACHED_BIT: {}",

memory_type.propertyFlags & VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_CACHED_BIT as VkMemoryPropertyFlags != 0

);

println!(

"Flag VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_LAZILY_ALLOCATED_BIT: {}",

memory_type.propertyFlags & VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_LAZILY_ALLOCATED_BIT as VkMemoryPropertyFlags != 0

);

}

Allocating memory

Now that we understand what memory types are and how they are related to heaps, we can make sense of what

memoryTypeBits means: whatever memory we allocate for our buffer, it needs to come from one of the

memory types whose index is present in this bitfield. More specifically we can check whether the memory type of

index i can back our buffer like this:

mem_requirements.memoryTypeBits & (1 << i) != 0.

Now it's time to allocate memory. We need to choose a supported memory type and allocate an instance of it,

however there may be multiple bits present in mem_requirements.memoryTypeBits. How do we decide

which memory type we want to allocate from? This is where the propertyFlags field of

VkMemoryType comes in. This bitfield tells us things about the memory type such as whether we can

map it and write it from the CPU (VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_VISIBLE_BIT), or whether it's backed by

memory that comes from VRAM (VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_DEVICE_LOCAL_BIT).

We want to copy the vertex data into this memory, so we want the VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_VISIBLE_BIT

and also don't want to bother with manually flushing memory writes so it will be visible to the GPU, so we also

want the VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_COHERENT_BIT.

The spec dictates an ordering between memory types present in VkPhysicalDeviceMemoryProperties.

This ordering according to the spec is

the following:

For each pair of elements X and Y returned in

memoryTypes, X must be placed at a lower index position than Y if:

- the set of bit flags returned in the

propertyFlagsmember of X is a strict subset of the set of bit flags returned in thepropertyFlagsmember of Y; or- the

propertyFlagsmembers of X and Y are equal, and X belongs to a memory heap with greater performance (as determined in an implementation-specific manner) ; or- the

propertyFlagsmembers of Y includesVK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_DEVICE_COHERENT_BIT_AMDorVK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_DEVICE_UNCACHED_BIT_AMDand X does not

In plain english this ordering ensures that if you are looking for strictly host visible and host coherent memory, and search from the lowest index, the first supported memory type you will find will be the dumbest possible. For instance, CPU accessible VRAM will have a higher index, and we won't select it accidentally. They even supply C++ code of the intended way of searching for a memory type, so let's follow it!

First let's create a variable that holds the memory property bits for our vertex buffer!

//

// Vertex data

//

// ...

// Vertex buffer size

// ...

let vertex_buf_mem_props = (VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_VISIBLE_BIT | VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_COHERENT_BIT) as VkMemoryPropertyFlags;

...and then select suitable memory! This is pretty much a rust adaptation of the C++ code in the linked chapter of the spec.

//

// Vertex buffer

//

// ...

// Create memory

// ...

let mut chosen_memory_type = phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount;

for i in 0..phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

if mem_requirements.memoryTypeBits & (1 << i) != 0 &&

(phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypes[i as usize].propertyFlags & vertex_buf_mem_props) == vertex_buf_mem_props

{

chosen_memory_type = i;

break;

}

}

if chosen_memory_type == phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

panic!("Could not find memory type.");

}

There. If there is a memory type that matches our criteria, this is how we find it. If we cannot find a desirable memory type, we will panic. I will give you ideas about handling such cases more gracefully in the next chapter.

Now that we have a memory type, it's time to allocate a piece of memory large enough to back our buffer. How do we know how big

our memory has to be? This is where the size field of VkMemoryRequirements helps us. We need at least

this much memory.

//

// Vertex buffer

//

// ...

// Create memory

// ...

let vertex_buffer_alloc_info = VkMemoryAllocateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_MEMORY_ALLOCATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

allocationSize: mem_requirements.size,

memoryTypeIndex: chosen_memory_type

};

println!("Vertex buffer size: {}", mem_requirements.size);

println!("Vertex buffer align: {}", mem_requirements.alignment);

println!("Allocating vertex buffer memory.");

let mut vertex_buffer_memory = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkAllocateMemory(

device,

&vertex_buffer_alloc_info,

core::ptr::null(),

&mut vertex_buffer_memory

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Could not allocate memory. Error: {}.", result);

}

Memory allocated. Let's add deallocation to the end!

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting vertex buffer device memory");

unsafe

{

vkFreeMemory(

device,

vertex_buffer_memory,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

Now we need to bind our buffer to the memory. This way our buffer will be backed by the memory we allocated. We do it like this:

//

// Vertex buffer

//

// ...

// Bind buffer to memory

println!("Binding vertex buffer memory.");

let result = unsafe

{

vkBindBufferMemory(

device,

vertex_buffer,

vertex_buffer_memory,

0

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to bind memory to vertex buffer. Error: {}.", result);

}

Now a range of the device memory is assigned to the buffer. Pay attention to the function's last parameter,

memoryOffset! Here we set it to zero, but in a real world application it would be the start of the memory

range. Now we can understand what the alignment field of VkMemoryRequirements is good for.

We can allocate large blocks of memory, and we can bind several buffers

(and later images) to different parts of these memory blocks.

If you do that, the value of memoryOffset must be aligned to the boundary of this alignment field.

memoryOffset passed to their

vkBindBufferMemory call.

Although using large allocations and avoiding per buffer allocations is the intended API usage, we go for simplicity in these tutorials. We will always create separate device memory for memory backed resources, and bind them with zero offset.

This is horrible API usage! When you are writing a real world application, avoid this scheme! Research best practices for your target hardware and follow those instead!

Uploading data

Now that our vertex buffer is created and memory is allocated for it, we want to populate this memory with the vertices of our triangle. We allocated host visible memory, so we can map the memory into the application's virtual address space.

//

// Uploading to Vertex buffer

//

unsafe

{

let mut data = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = vkMapMemory(

device,

vertex_buffer_memory,

0,

vertex_data_size as VkDeviceSize,

0, &mut data

);

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to map memory. Error: {}", result);

}

// ...

}

This mapped the physical memory represented by the vertex buffer's device memory into the virtual address space of our program, and gave us a pointer to the beginning of this mapping.

We can use this pointer to copy the vertex data into our device memory.

//

// Uploading to Vertex buffer

//

unsafe

{

// ...

let vertex_data: *mut f32 = core::mem::transmute(data);

core::ptr::copy_nonoverlapping::<f32>(

vertices.as_ptr(),

vertex_data,

vertices.len()

);

// ...

}

Now that our vertex data is copied into the vulkan device memory, we no longer need it to be mapped into virtual memory, so we can unmap it.

//

// Uploading to Vertex buffer

//

unsafe

{

// ...

vkUnmapMemory(

device,

vertex_buffer_memory

);

}

Buffer creation summary

Let's sum it all up! We have done all the low level details, but let's assemble the big picture! We decided that we want to specify the vertices of our triangle meshes from memory. Then we created a Buffer, which is a memory backed resource suitable to reference these vertices in memory. Then we queried its memory requirements, allocated some suitable device memory, bound the buffer to this memory to make the buffer backed by this memory, and then uploaded the vertex data into the memory that backs our buffer.

Now that our vertices are in GPU accessible memory, we need to reparametrize our pipeline to communicate the data source and format of our vertex data.

Pipeline Vertex input state

Now that our vertex data is uploaded into GPU accessible memory, we need to access it from our vertex shader. The format of the vertex data is a property of the graphics pipeline. The part of the pipeline we need to modify is the vertex input state. In the previous chapter, we left it empty. Now it's time to go into details!

// From the previous tutorial...

let vertex_input_state = VkPipelineVertexInputStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_VERTEX_INPUT_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

vertexBindingDescriptionCount: 0,

pVertexBindingDescriptions: core::ptr::null(),

vertexAttributeDescriptionCount: 0,

pVertexAttributeDescriptions: core::ptr::null()

};

As we can see there are two parameters in this struct: a list of bindings and a list of attributes.

Bindings are indirections for Vertex buffers. You can plug Vertex buffers into bindings during rendering.

Bindings have an index, and in the VkVertexInputBindingDescription struct you can specify which

bindings you want to use, and what the stride will be between the individual per vertex attribute data.

In this tutorial we will have a single binding.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let vertex_bindings = [

VkVertexInputBindingDescription {

binding: 0,

stride: 2 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>() as u32,

inputRate: VK_VERTEX_INPUT_RATE_VERTEX,

}

];

The field binding contains an integer identifier, which will be used during attribute definition.

The stride contains the amount of bytes between the beginnings of the data of consecutive vertices.

We have 2 dimensional float vectors, these two floats are tightly packed, and the next vertex data is also

tightly packed right next to it, so it takes 2 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>() bytes to step from

one vertex data to the next. This will be the stride. The inputRate is a parameter related to a more

advanced feature called Instancing. Instancing is out of scope for this tutorial, we won't get into it, and we just

set this value to VK_VERTEX_INPUT_RATE_VERTEX without elaborating.

Attributes define input variables to the vertex shader. In the VkVertexInputAttributeDescription you

can specify the location, which is an identifier we will refer to in the vertex shader, the source binding, the

format and the offset of the data within the binding. In this tutorial we have one location that supplies a 2D

float vector starting at the beginning of the zeroth binding.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let vertex_attributes = [

VkVertexInputAttributeDescription {

location: 0,

binding: 0,

format: VK_FORMAT_R32G32_SFLOAT,

offset: 0,

}

];

The field location will be important, because this number will identify the attribute in the

shader. The binding identifies the binding the data comes from, and offset determines

its offset within the binding. Both will be zero. Vertex attributes must have

their formats specified, this is what format is for, and VK_FORMAT_R32G32_SFLOAT

means that it will be a two component float vector.

We will reference these two structs in our vertex input state create info.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let vertex_input_state = VkPipelineVertexInputStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_VERTEX_INPUT_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

vertexBindingDescriptionCount: vertex_bindings.len() as u32,

pVertexBindingDescriptions: vertex_bindings.as_ptr(),

vertexAttributeDescriptionCount: vertex_attributes.len() as u32,

pVertexAttributeDescriptions: vertex_attributes.as_ptr()

};

In a more complicated situation you can use multiple bindings and multiple vertex attributes. The illustration of the previously introduced concepts can be seen below.

Now that we specified the bindings and the vertex attributes, it's time to bind our vertex buffer to these bindings.

Binding vertex buffer

Now that our pipeline is set up it's time to reference our vertex data in memory. Like I said, most of the time

in Vulkan you do not reference memory directly, but instead use memory backed resources. In our case, a buffer.

The way we reference the piece of memory that holds vertex data is done by binding the vertex buffer to the

bindings specified during pipeline creation. This is done by calling vkCmdBindVertexBuffers.

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

// ...

let vertex_buffers = [

vertex_buffer

];

let offsets = [

0

];

vkCmdBindVertexBuffers(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

0,

vertex_buffers.len() as u32,

vertex_buffers.as_ptr(),

offsets.as_ptr()

);

vkCmdDraw(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

3,

1,

0,

0

);

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

Pay attention, that with one vkCmdBindVertexBuffers call you can bind several vertex buffers, or the

same vertex buffer with different offsets to subsequent bindings.

Now that the bindings are specified in the pipeline and vertex buffers are actually bound to these bindings, it's time to adjust the shaders so they actually make use of the data present in the bound buffers.

Adjusting the shader

During pipeline creation we have specified an attribute that the vertex shader can use as data source. We need to add a variable representing this attribute and use the specified attribute location to pair the variable defined in the shader to the attribute specified in the pipeline. The resulting shader code can be seen below.

#version 460

layout(location = 0) in vec2 position;

void main()

{

gl_Position = vec4(position, 0.0, 1.0);

}

Instead of hardcoding the triangle into the mesh, we have created an attribute variable called

position. The in keyword before its type marks it as an attribute. We need to connect

this attribute variable to the attribute defined during pipeline creation, and this is what

layout(location = 0) does: it sets the attribute location. Since we specified the position attribute

to be at location 0 during pipeline creation, we need to assign 0 to the attribute location of the variable, and

they will all be connected.

Then we can use this position variable where we initially used the array element.

I saved this file as 01_attrib_position.vert into the shader_src/vertex_shaders

directory created in the previous chapter.

Let's compile it with the following command:

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/01_attrib_position.vert.spv ./shader_src/vertex_shaders/01_attrib_position.vert

Once our binary is ready, we need to load this new binary instead of our hardcoded triangle shader.

//

// Shader modules

//

// Vertex shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/01_attrib_position.vert.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

// ...

...and that's it! Now we have a draw call that executes a shader that reads our new triangle from memory and draws it onto the screen!

Vertex buffer summary

Now that we can finally draw a model from memory let's summarize what we learned. We introduced ourselves to

buffers, that are memory backed resources representing linear memory. We learned how to allocate memory in Vulkan

and how to bind memory to a buffer, how to reference a vertex buffer during rendering using

vkCmdBindVertexBuffers, how to specify vertex attributes and bindings during pipeline creation and

how to use these vertex attributes in a vertex shader.

There is only one problem: if we tried to define a larger triangle mesh with the same vertex reused in many triangles, we would need to duplicate the vertex for every triangle that uses it. Then the vertex shader would need to be run for every duplicate. Vulkan's solution to deduplicate vertices is the index buffer.

Index buffer

We have drawn a triangle the simplest possible way. Real world models however are made out of several triangles. Some triangles may share vertices. For instance, a quad can consist of two triangles, and these triangles sharing two vertices.

If we filled a vertex buffer with these triangles as a triangle list, we would need to duplicate these shared vertices. This memory would need to be transferred from memory to the GPU cores, a separate vertex shader instance would run for them, and this is not very efficient.

This is where index buffers can help us.

In Vulkan index buffers are buffers containing a list of integers that define primitives. These integers are indices identifying vertex data in a vertex buffer. The way primitives are constructed from these integers is defined by the input assebmly state's primitive topology.

Now the VK_PRIMITIVE_TOPOLOGY_TRIANGLE_LIST primitive topology from the

previous tutorial comes into play, as I promised.

This dictates how our triangles need to be laid out in memory. For VK_PRIMITIVE_TOPOLOGY_TRIANGLE_LIST

every integer triplet defines a single triangle.

With an index buffer we upload vertices into the vertex buffer, we do not duplicate more vertices than what's needed, and have a separate buffer to define primitives by the index of their vertices. Then during rendering we bind this index buffer as well and issue a separate kind of draw call, an indexed draw call. There can be less duplication in the vertex buffer, and the GPU may be able to avoid running the vertex shader multiple times for the same vertex.

VK_PRIMITIVE_TOPOLOGY_TRIANGLE_LIST primitive topology, every integer triplet in the index

buffer defines a single triangle.

Allocating the index buffer is almost the same as allocating the vertex buffer. The usage bits will be different but the rest will be the same.

Preparing index data

First we will render our single triangle with an indexed draw call to familiarize ourselves with the API. The data is straightforward: we want to draw a triangle defined by the first, the second and the third vertex.

Then we hardcode the triangle indices into a vector of integers.

//

// Vertex and Index data

//

let vertices: Vec<f32> = vec![

// Triangle

// Vertex 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

1.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, 1.0,

];

let indices: Vec<u32> = vec![

// Triangle

0, 1, 2,

];

// Vertex and Index buffer size

let vertex_data_size = vertices.len() * core::mem::size_of::<f32>();

let index_data_size = indices.len() * core::mem::size_of::<u32>();

// ...

Pay attention that we were very explicit about incides being a u32 array for the same reason we were

explicit about vertex data being a f32 array!

Creating the Index buffer

Like I said, this will be almost the same as creating the vertex buffer. We create our buffer with the right usage flags, create the buffer, get the memory requirements, find a suitable memory type, allocate memory, bind the buffer to the memory and enjoy.

Let's create our memory property flags!

//

// Vertex and Index data

//

// ...

// Vertex and Index buffer size

// ...

let index_buf_mem_props = (VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_VISIBLE_BIT | VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_COHERENT_BIT) as VkMemoryPropertyFlags;

Let's just create our index buffer in one sample code, because we already know the steps!

//

// Index buffer

//

// Create buffer

let index_buffer_create_info = VkBufferCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_BUFFER_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

size: index_data_size as VkDeviceSize,

usage: VK_BUFFER_USAGE_INDEX_BUFFER_BIT as VkBufferUsageFlags,

sharingMode: VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE,

queueFamilyIndexCount: 0,

pQueueFamilyIndices: core::ptr::null()

};

println!("Creating index buffer.");

let mut index_buffer = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateBuffer(

device,

&index_buffer_create_info,

core::ptr::null(),

&mut index_buffer

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create index buffer. Error: {}.", result);

}

// Create memory

let mut mem_requirements = VkMemoryRequirements::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetBufferMemoryRequirements(

device,

index_buffer,

&mut mem_requirements

);

}

let mut chosen_memory_type = phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount;

for i in 0..phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

if mem_requirements.memoryTypeBits & (1 << i) != 0 &&

(phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypes[i as usize].propertyFlags & index_buf_mem_props) == index_buf_mem_props

{

chosen_memory_type = i;

break;

}

}

if chosen_memory_type == phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

panic!("Could not find memory type.");

}

let index_buffer_alloc_info = VkMemoryAllocateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_MEMORY_ALLOCATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

allocationSize: mem_requirements.size,

memoryTypeIndex: chosen_memory_type

};

println!("Index buffer size: {}", mem_requirements.size);

println!("Index buffer align: {}", mem_requirements.alignment);

println!("Allocating index buffer memory.");

let mut index_buffer_memory = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkAllocateMemory(

device,

&index_buffer_alloc_info,

core::ptr::null(),

&mut index_buffer_memory

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Could not allocate memory. Error: {}.", result);

}

// Bind buffer to memory

println!("Binding index buffer memory.");

let result = unsafe

{

vkBindBufferMemory(

device,

index_buffer,

index_buffer_memory,

0

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to bind memory to index buffer. Error: {}.", result);

}

The variable names and usage flags are different, but the rest is the same.

Also cleanup!

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting index buffer device memory");

unsafe

{

vkFreeMemory(

device,

index_buffer_memory,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

println!("Deleting index buffer");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyBuffer(

device,

index_buffer,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

Uploading data

This is also done almost the same way as the vertex buffer: we map, upload and unmap.

//

// Uploading to Index buffer

//

unsafe

{

let mut data = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = vkMapMemory(

device,

index_buffer_memory,

0,

index_data_size as VkDeviceSize,

0,

&mut data

);

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to map memory. Error: {}.", result);

}

let index_data: *mut u32 = core::mem::transmute(data);

core::ptr::copy_nonoverlapping::<u32>(

indices.as_ptr(),

index_data,

indices.len()

);

vkUnmapMemory(

device,

index_buffer_memory

);

}

Indexed draw call

In order to use the index buffer, we need to first bind it like we did with the vertex buffer, and issue a different kind of draw call, an indexed draw call.

Index buffer binding is done by calling vkCmdBindIndexBuffer.

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

// ...

vkCmdBindIndexBuffer(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

index_buffer,

0,

VK_INDEX_TYPE_UINT32

);

// Draw triangle without index buffer

vkCmdDraw(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

3,

1,

0,

0

);

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

We supplied the index buffer, an offset of zero, since our index data starts at the beginning of the buffer, and the data type of the indices, which is 32 bit unsigned integer.

Then we need to record a different kind of draw command, vkCmdDrawIndexed. Let's comment out the old

vkCmdDraw and replace it with the new one!

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

// ...

vkCmdBindIndexBuffer(cmd_buffers[current_frame_index], index_buffer, 0, VK_INDEX_TYPE_UINT32);

// Draw triangle without index buffer

//vkCmdDraw(

// cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

// 3,

// 1,

// 0,

// 0

//);

// Draw triangle with index buffer

vkCmdDrawIndexed(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

3,

1,

0,

0,

0

);

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

This recorded an indexed draw command. The important parameters are indexCount, which is

3, because we have three integers defining our triangle, and instanceCount,

which is 1, because we draw only one instance. We assign zero to the rest, and do not

go into details about them yet.

If we run our program, it draws a triangle to the screen, just like before, but with an indexed draw call.

Index buffer summary

In this section you have learned about index buffers, which is a new way of defining primitives with a list of vertex indices. They help with avoiding vertex data duplication. You have learned how to create them, bind them during rendering and use them with an indexed draw call.

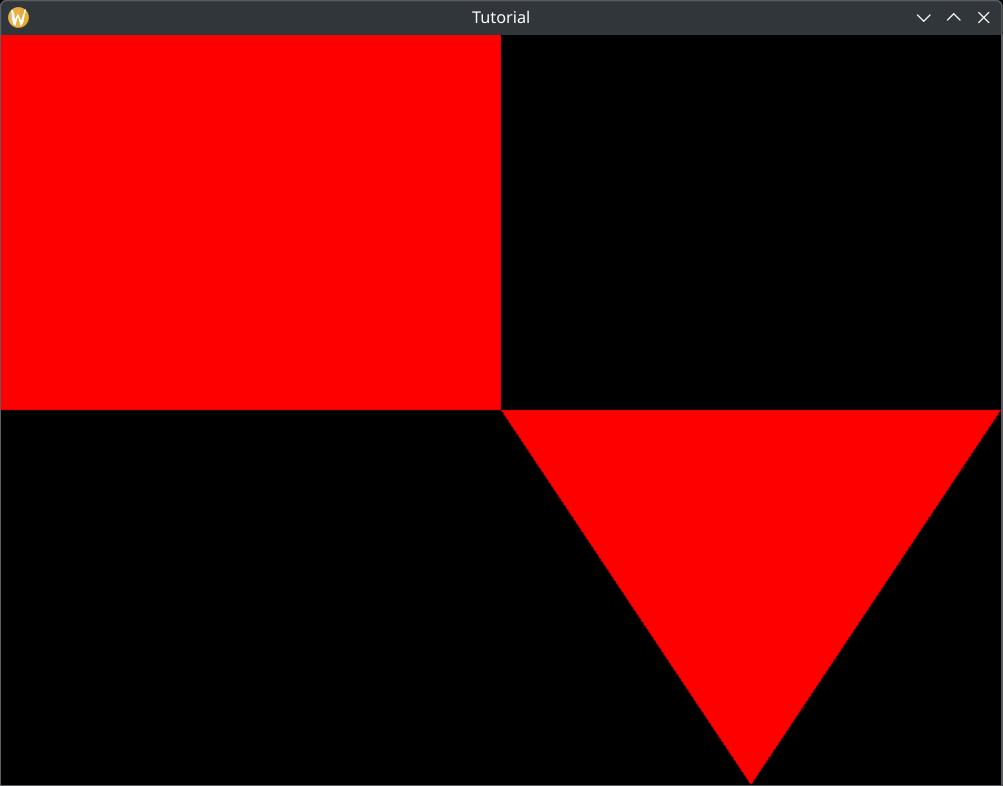

Bonus: drawing an additional quad

We have drawn a triangle to familiarize ourselves with index buffers and indexed draw calls, but a single triangle does not illustrate the vertex reuse promised by indexed draw calls. Beyond that this is an excellent opportunity to show you a nice API usage for storing and rendering multiple models that does not kill performance. So... let's render a second model, a quad as well!

Preparing data

First let's get our pen and paper again, let's draw a coordinate system again, and let's draw our new quad.

Next we assign an array index to every vertex, break down our quad into two triangles and define every triangle with the indices of its vertices. We can clearly see better vertex reuse already on Figure 11. The vertex reuse gets more significant for larger meshes.

You may see other tutorials on the internet that would consider this quad to be a new mesh, and would create a dedicated vertex and index buffer for it, but that is horrible API usage. In the OpenGL days such practices killed performance and promoted new ways of using the graphics API. This was "Approach Zero Driver Overhead". They had a GDC presentation with slides.

Creating a new vertex and index buffer per mesh is not a good practice in Vulkan either. Binding multiple

buffers takes longer than binding a single buffer, because you have to record multiple buffer binding commands

that need to be executed. This is confirmed by the

AMD performance recommendations where it does not recommend

setting vertex streams per draw call

.

NVidia has its own article about memory management where at the end they even recommend placing vertex, index and other kinds of data into a single buffer, and supply offsets during buffer binding. (although this would require adding multiple usage flags to the buffers as well, which is not encouraged by AMD.)

Various mobile vendors also have their optimization guides. In a real world application decide what your list of target hardware is, read their guides, and decide who you listen to.

We are going append the quad at the end of our vertex buffer and index buffer. This is the right way to think about vertex and index buffers: think about them as memory pools! You allocate large buffers and load multiple meshes into them. You can supply a starting vertex and index to the draw calls to decide which mesh you want to render. This way you don't have to rebind them in the command buffer if you want to render a different mesh as long as it resides in the same buffers.

//

// Vertex and Index data

//

let vertices: Vec<f32> = vec![

// Triangle

// Vertex 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

1.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, 1.0,

// Quad

// Vertex 0

-1.0, -1.0,

// Vertex 1

0.0, -1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 3

-1.0, 0.0

];

let indices: Vec<u32> = vec![

// Triangle

0, 1, 2,

// Quad

// First triangle

0, 1, 2,

// Second triangle

0, 2, 3

];

Indexed draw call

Now that our quad is appended to the existing vertex and index buffer, it's time to render it. You may ask,

"How will this draw call know, which vertex and index does our mesh start with?", and the answer is: we can

supply it as parameter to vkCmdDrawIndexed. These parameters are the firstIndex

and vertexOffset. Two of the parameters we assigned zero to and didn't discuss.

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

// ...

// Draw triangle with index buffer

vkCmdDrawIndexed(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

3,

1,

0,

0,

0

);

// Draw quad with index buffer

vkCmdDrawIndexed(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

6,

1,

3,

3,

0

);

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

The firstIndex parameter will make sure that the indexed draw call will start at an offset, and

vertexOffset is a value that will be added to every individual index, making the indices refer

to an offsetted region of the vertex buffer.

The triangle resides in the beginning of the buffer, therefore the geometry is identified by the parameters

firstIndex = 0, vertexOffset = 0 and indexCount = 3.

The quad is right after the triangle, so that is identified by the parameters

firstIndex = 3, vertexOffset = 3 and indexCount = 6.

This allows you to use your vertex and index buffers as mesh pools, storing multiple triangle meshes in a single vertex and index buffer that can be bound once for many draw calls.

firstIndex and vertexOffset parameters of

vkCmdDrawIndexed function.

Let's run the application and see the results:

Wrapping up

That was quite massive. We needed to draw triangles that are stored in memory. We familiarized ourselves with buffers, which are memory backed resources. We allocated suitable memory objects for them and bound the buffers to them, uploaded data into memory and used the buffers during rendering.

We learned how to store vertices in a vertex buffer and referred to these vertices during rendering by binding this vertex buffer before draw calls. We adjusted the pipeline definition to supply the data format of the vertices and the shader to use the buffer contents in its calculations.

We then realized that using only vertex buffers would lead to unnecessary vertex data duplication. We learned about indexed draw calls, created an index buffer, stored index data defining our triangles in the memory of the buffer, referred to this data by binding the index buffer and issued an indexed draw call.

In the next chapter we will move the vertex and index buffers into VRAM, (if we have VRAM) and transfer vertex and index data to them using transfer commands.

The sample code for this tutorial can be found here.

The tutorial continues here.