Diffuse lighting

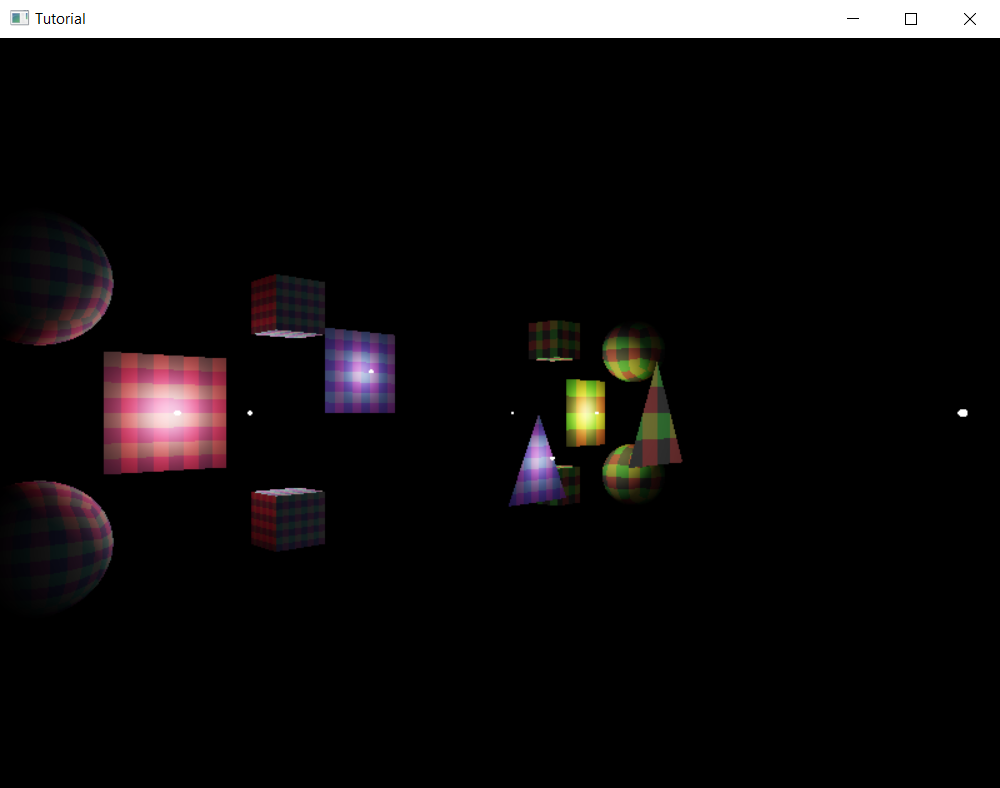

In the previous chapter we finally learned depth buffering, and that covered the basics of the Vulkan API and 3D rendering.

In this chapter we get started with lighting.

We will need to simulate lighting in our 3D scene, and to do that we will learn about the physics behind lighting. We will learn about a theoretical rendering equation and we will specialize it for direcr illumination, point lights and diffuse lighting. This will be a good foundation for real time rendering.

Then we will need to fill our swapchain images with RGB pixel data based on the simulated physical quantities, and to do that we will learn about physically based cameras, exposure correction, tonemapping and gamma correction.

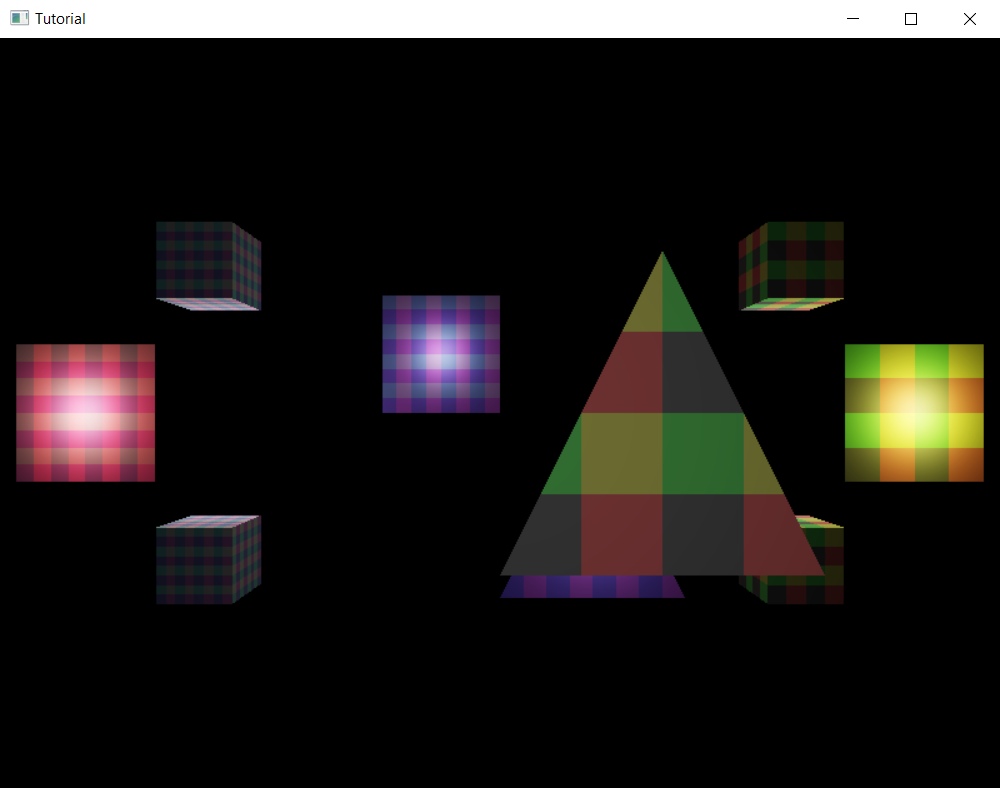

After studying the theory, we will extend our depth buffered 3D application from the previous chapter to perform lighting calculations using the specialized rendering equation, and write RGB pixel data to the swapchain image derived from its results.

This tutorial is math and physics heavy and assumes you already have some intuition for calculus. The recommendations from the previous tutorials for consuming math still apply: you can understand math in many ways, depending on your way of thinking and background:

- Read and understand the math first, then the code

- Understand the code first, and then interpret the math

Read whichever way is better for you. Be prepared that multiple rereads may be necessary.

This tutorial is in open beta. There may be bugs in the code and misinformation and inaccuracies in the text. If you find any, feel free to open a ticket on the repo of the code samples.

Radiometry and the Rendering equation

Physically based rendering is about calculating how light ends up in the camera using equations derived from physics. Light is electromagnetic radiation described by a branch of physics called electrodynamics. Practicioners of computer graphics tend not to use Maxwell's equations directly, but instead introduce layers of abstractions and run simulations using much simpler equations than Maxwell's equations.

This section briefly summarizes the physics behind rendering. The human eye and cameras detect energy from light. We will introduce a physical quantity related to energy that we can use to determine the brightness of pixels, and an equation we can use to calculate the said physical quantity for every pixel based on how light travels from light sources through the scene to the camera.

This section is based on the computer graphics course of Two Minute Papers youtube channel.

Radiance

The brightness of the pixel is going to be calculated based on a physical quantity related to energy, but what is this physical quantity? This is explored in the aforementioned computer graphics course's Radiometry video.

There is a physical quantity called the radiant power measured in Watts . This is not good enough because of ambiguity: is there a small amount of power coming from a large surface or a large amount coming from a small surface? The amount of radiant power that we measure would be the same, but the distribution of the radiant power would be way different.

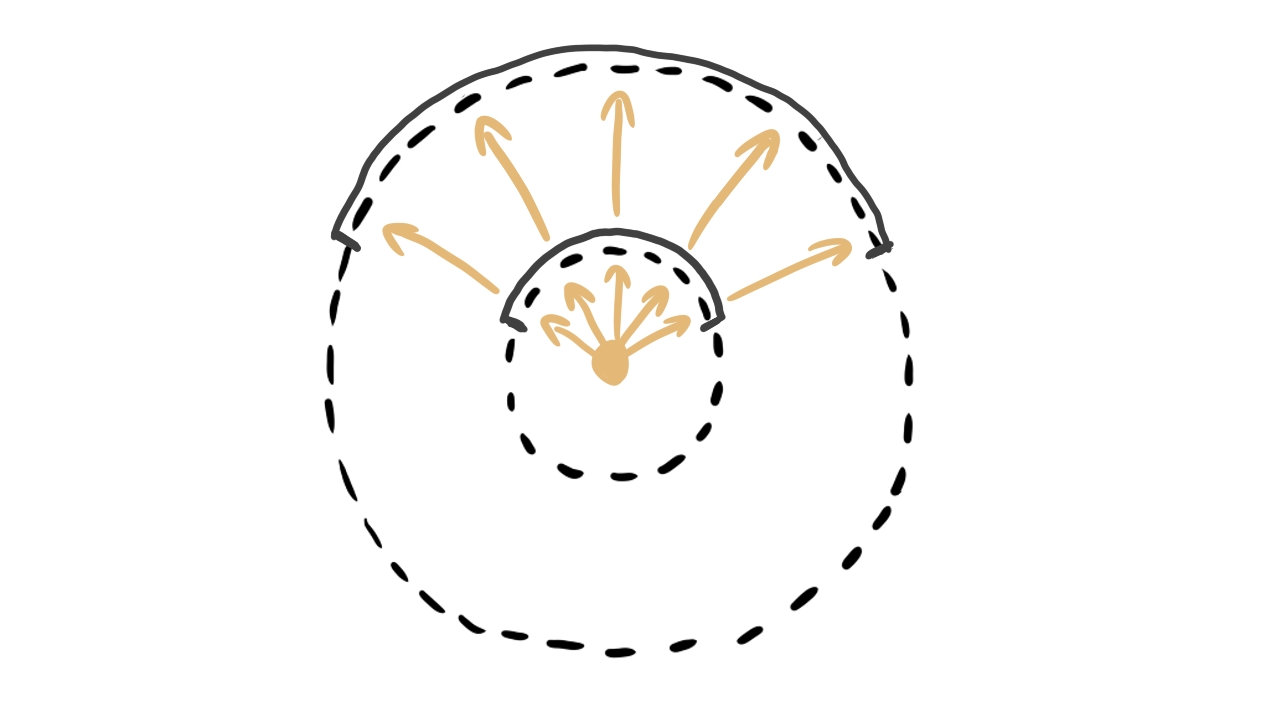

Let's try to get rid of the ambiguity! Let's get the radiant power per unit area! This is called irradiance and it's measured in Watts per square meter . This is still not good enough because of ambiguity: is there a large amount of power coming from a large solid angle or a small amount coming from a small solid angle?

Let's follow the same idea and try to get the radiant power per area per solid angle! This is called radiance and it's measured in Watts per steradian per square meter . This finally removes all of the ambiguities.

Rendering equation

We have our physical quantity, radiance. Now we need equations that help us simulate how much radiance ends up in a pixel of our swapchain image.

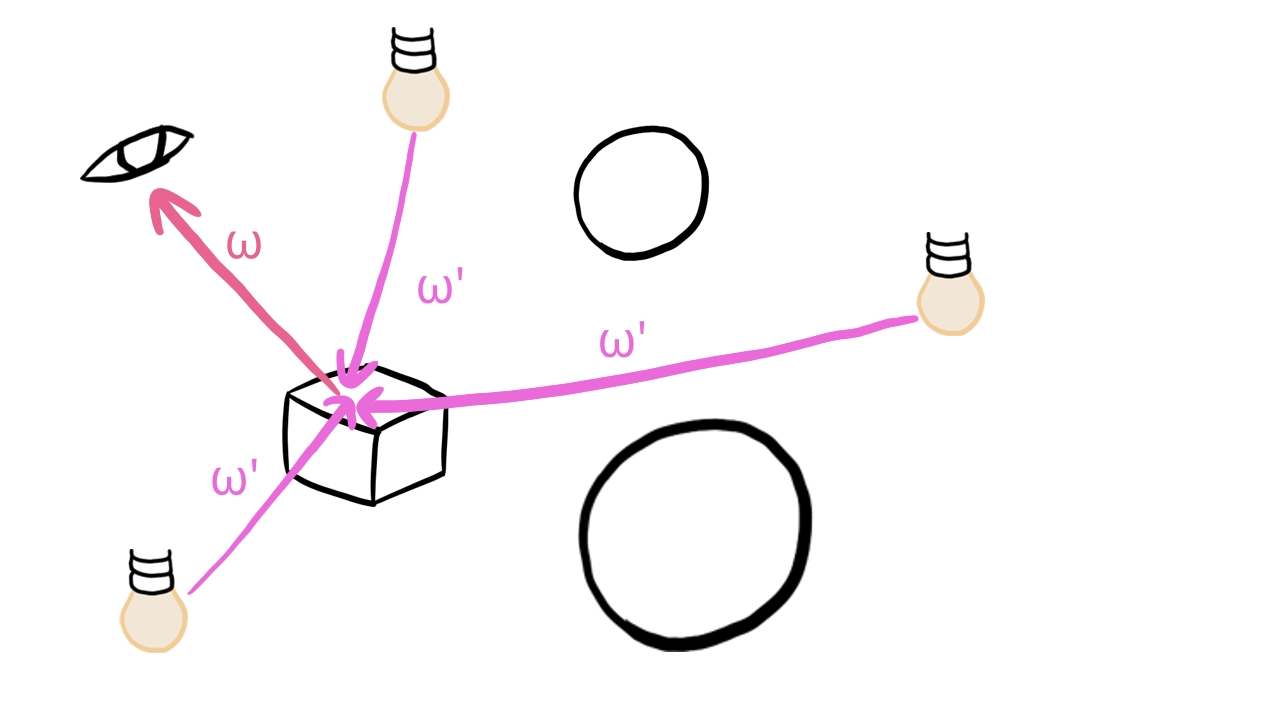

We use a probabilistic model. We assume that incoming light coming from one direction can get reflected in many directions with certain probabilities, or may get absorbed by the surface. If we are curious about a certain direction, such as the direction of the camera, the probability tells us how much of the incoming radiance gets reflected towards the camera.

The equation starts to get introduced in the previously mentioned video, but only this one starts to get into details we need. The equation that we need to calculate the emitted light in terms of the incoming light is introduced below.

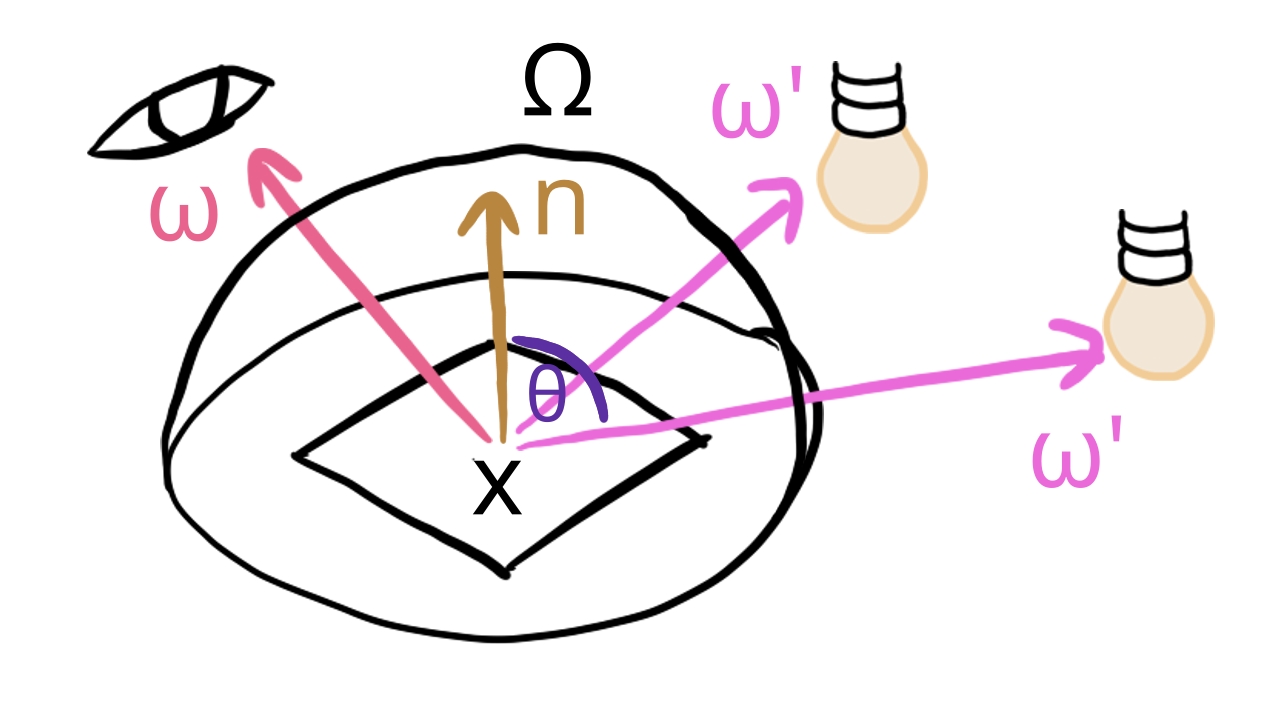

Let our surface element that covers a pixel be at point and let the direction vector pointing from the surface to the camera be ! We want to figure our what radiance leaves the surface from point to direction . The value of this radiance is given by the following equation called the Rendering equation.

The radiance equals to the sum of the emitted radiance emitted by the surface and the reflected radiance. The reflected radiance for a given equals to the sum of incoming radiance from this direction, multiplied by a probability density function that gives the probability of the surface at point reflecting light from direction to direction , weighted by the surface element's projected area. This probability function is called Bidirectional reflectance distribution function. You see that there is a multiplication inside the integral with the cosine of the angle , which is the angle between the direction and the surface's normal at point . This cosine is the scaling factor between the surface element's projected area at point and the actual area. We need to sum this up to the whole hemisphere. In our model the hemisphere contains infinite directions continuously, so summing up the reflected radiance for all of these directions is done using an integral.

This equation is actually an infinite recursive equation, as the incoming radiance for every direction leaves a surface element at point also calculated by the Rendering equation.

Such integrals cannot be evaluated on our computers. We need to specialize this problem. In this tutorial are going to simplify this equation. We will solve a simplified version that is not infinitely recursive, not an integral and the probability density function is very simple.

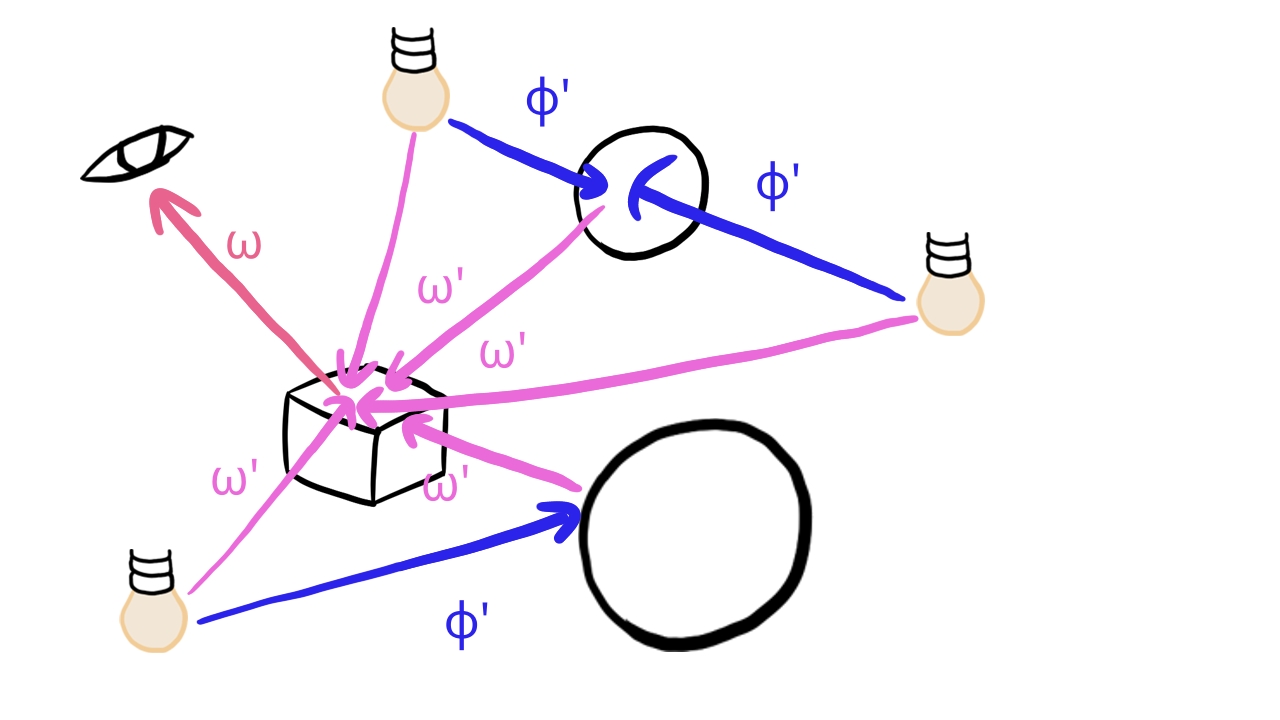

Direct illumination

First we cut off our recursion. Generally light bounces around and sometimes light reflected from other scene elements illuminate a scene element visible in a certain pixel. The recursion accounts for that as well. It aggregates incoming radiance from many sources. Solving that problem is called global illumination. In this article we will not go into that. Instead the brightness of our pixels is only affected by the radiance coming from the light sources directly. Since we remove indirect lighting, the formula for the incoming radiance is simplified like this:

This modified formula will only take emissive light from scene elements into account inside the integral. No light that bounces around will be taken into account.

Calculating this exactly would still be pretty computationally intensive, because we need to find the closest hit along our direction . We simplify this by cheating a lot.

We group our scene elements into two groups: objects and lights. Lights will not be rendered directly, but they will emit radiance. Objects will be rendered directly, and their surface will reflect radiance coming only from lights.

Basically objects will not reflect other objects' emitted radiance, only lights' emitted radiance. This gets rid of many interdependencies of the reflected radiances of scene elements and decreases the algorithmic complexity of lighting.

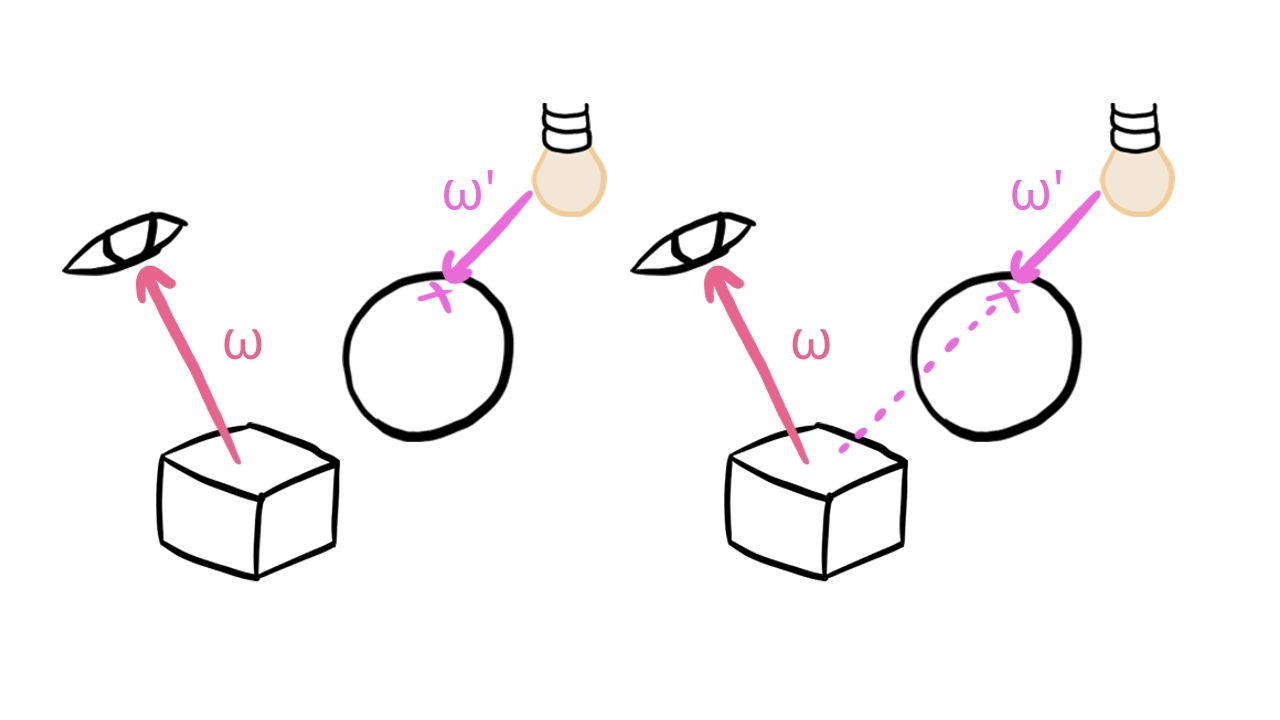

After this step we still have a bit of problem. Objects generally cast shadows, and to take that into account, we would have to find out when collecting radiance from a light if there is a triangle obstructing the light path. To get rid of this interdependency, objects will also not cast shadows. This will greatly decrease algorithmic complexity, because collecting the reflected radiance from light sources turns into a simple iteration over every light. In every iteration we collect a given light's contribution from the given direction. No need to check for occlusion by objects.

So far our incoming light equation looks like this:

If an object covers a pixel, the color of the pixel will be determined by the model's emissive lighting and the incoming radiance of the light sources.

With these steps we have greatly decreased the complexity of our rendering equation, but there is still an integral in it, and without further assumptions a computer program still cannot be written to calculate it.

Point lights

In order to get rid of that integral we need some assumptions about our light sources.

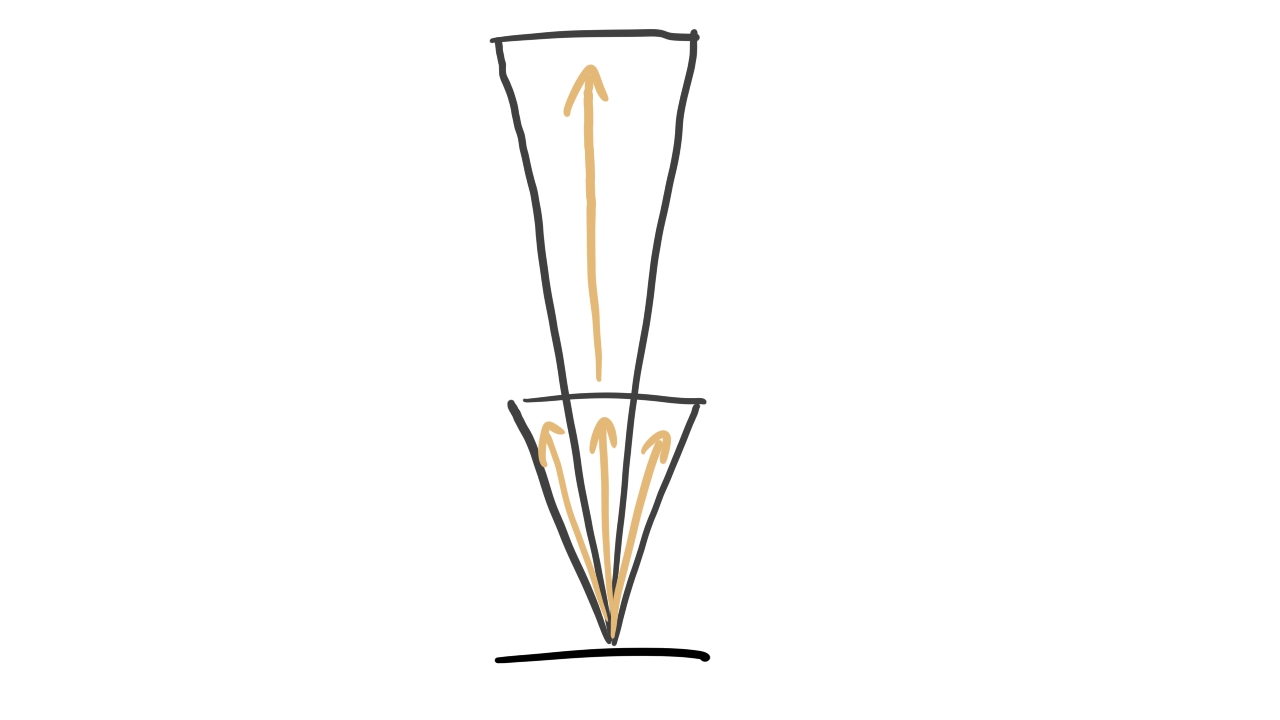

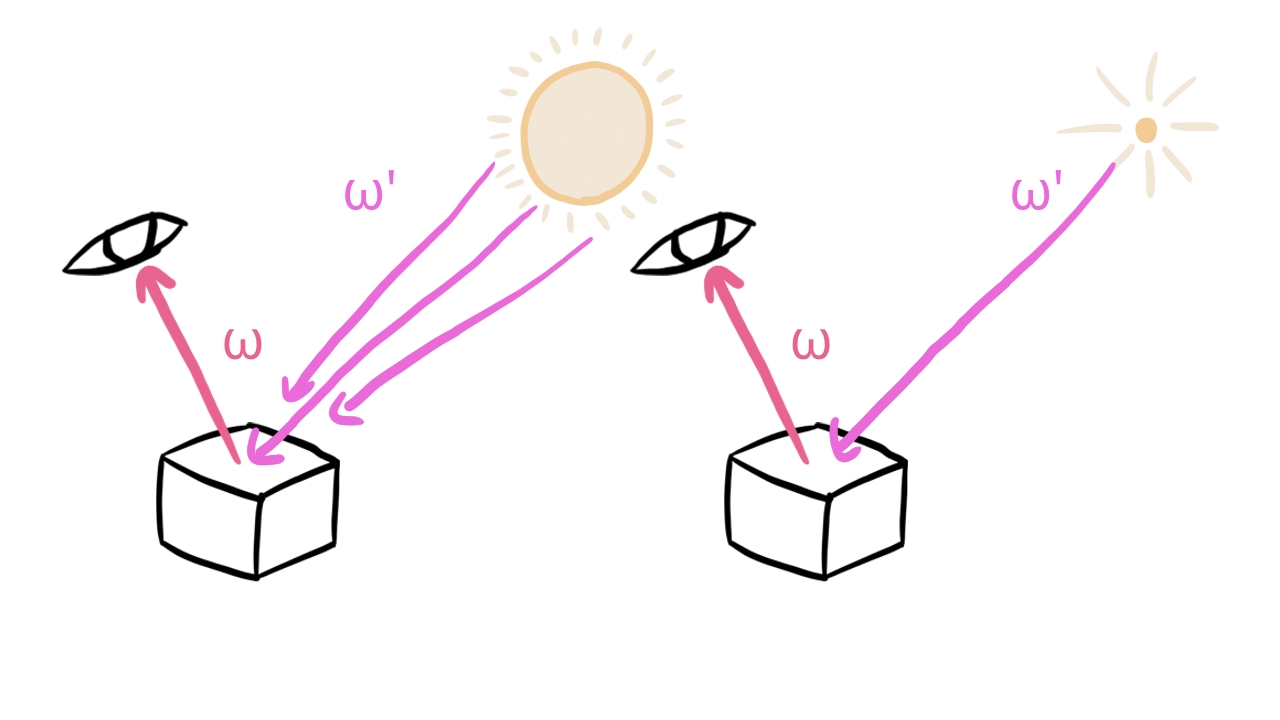

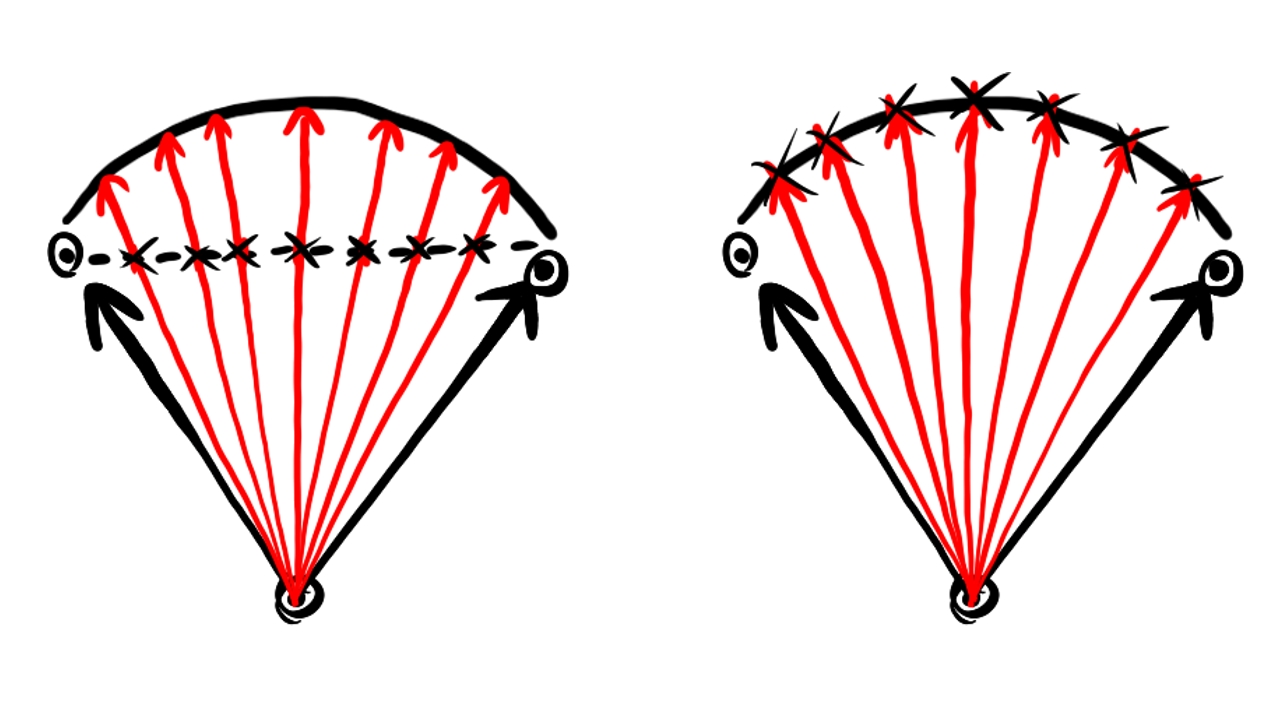

If our light has a volume, we need to integrate for its whole surface. This is where point lights come in. Point lights emit light from a specific point, so no need to integrate over a surface.

Our integral and the choice of our units of measurement were prepared for light sources that have an area, but point lights do not have that. We need to figure out some hack to collect radiance contribution from our point light.

According to the PBR book it is incorrect to use radiance to describe the amount of light arriving at a point from a point light, and we should use the radiant intensity instead: the amount of radiant power exiting the light source per solid angle. We assume that based on this physical quantity the point light distributes radiance evenly in all directions.

The problem is that this is a different physical quantity with a different dimension. It contains the information needed to figure out how much energy the light source emits, but technically it is not directly usable.

How can we get from having to having something we can plug into our integral? There are multiple lines of thought that can build up the intuition for the formula used in the industry.

One is looking at other energy related physical quantities. For instance let's look at the irradiance :

This is power per area. If the power of a point light gets evenly distributed across the surface of a sphere, this quantity would decrease with the inverse square of the radius. It is also a function of the radiant intensity. Its dimensions are also much friendlier than the dimension of radiant intensity.

This tells us that the amount of power coming from the point light to a surface element at distance decreases with the inverse square of . Our intuition should say that our "radiance" at distance should behave the same way.

There is a second line of thought trying to build up the same intuition. is the amount of

radiant power per unit solid angle. Let's have a surface element with an area that is lit

by our point light! How does the solid angle change if we increase the distance? According to

Wikipedia,

the solid angle is related to the area it cuts out from the

sphere.

In our case is the solid angle, is the area of our surface and is the distance from our point light. Let's measure in square meters and in meters! If we choose our surface to have an area , then the radiant power reaching the surface will be:

The formula looks very similar to the previous one but pay attention that the dimensions are not the same! What this is good enough is building up the intuition: the further we are, the radiant power reaching the surface will be proportional to the inverse square of the distance.

These ideas lead to the formula commonly used. If we divide by , we will get a physical quantity that has the same dimension as the radiance and will represent the amount of light decreasing with the inverse square of the distance.

We want to return this when the direction in the integral is the direction from the surface to the point light.

Let's construct a model for a single point light! We choose to be a "function", where is the direction from the surface element to the point light, is the distance of point from the position of the point light and is the Dirac delta. If we plug this into our integral, a single point light our integral simplifies the following way:

The integral disappeared. Radiance from multiple lights is a simple sum.

We have gotten far. No infinite recursion and no integral, but we still have an unknown function f, which is a function that determines what the probability of reflecting the radiance towards a given point is. We can choose this function for ourselves, so let's choose a popular one!

Diffuse BRDF

The BRDF function tells us what is the probability of a surface element at point reflecting light from light direction to the view direction .

A very simple and widely used BRDF is the Lambertian model, which is suitable for perfectly matte surfaces. The Lambertien BRDF is the constant BRDF: it reflects light in every direction with equal probability. This probability may be small or large, depending on the probability of reflecting or absorbing light, but it is independent of the viewing angle.

How should we choose this constant function? We want it to be physically based, because we can handle that better in later tutorials. According to Wikipedia it should be larger than zero, and the integral of the function for the whole hemisphere should be less than one. In Epic's Real Shading in Unreal Engine 4 the diffuse BRDF is the following: let be the diffuse albedo of the material, . The diffuse BRDF will be:

We can plug this BRDF into our rendering equation and finally have something we can write in a shader.

Resulting simplified rendering equation

So far we have made the following assumptions:

- We only calculate local illumination.

- Objects do not cast shadow.

- Out light sources will be point lights.

- The BRDF of our objects will be Lambertian diffuse BRDF.

With these assumptions our simplified rendering equation looks like this:

No infinite recursion, no integrals and we can calculate the color of every object using only its data and the list of lights affecting it. We are going to evaluate this formula for three wavelengths: the wavelength of the red color, the green color and the blue color. This way everything that is the function of will become a number triplet.

Now that we have radiance, which can be anywhere from zero to infinity, we need to map it into the range, because that's the range of values that can be stored in our swaphcain image. There are two things that need to be done to achieve this: first we do exposure compensation, and then do tone mapping.

Exposure correction

The human eye and cameras are all capable of forming images in both poorly lit and very well lit environments. Your pupil can get wider to let more light in when you are in a dark area, and narrower when you are in a well lit area. Cameras can collect more or less light as needed by adjusting the lens aperture or the shutter speed.

With this feature both the human eye and a camera can form a useful image in both dark caves and bight landscapes by controlling the amount of light entering the detector, visualizing dark areas lighter and light areas darker so they fall in the detectable range.

This process is called exposure correction. Exposure correction allows us to brighten or darken the image depending

on the lighting conditions, instead of having to tweak the lights in the scene. It removes a lot of manual work.

To perform exposure correction we need some kind of mathematical model that gives us formulae that we can write

down as code.

In this section we go over the A Physically Based Camera

section of

Moving Frostbite to PBR

document.

We introduce the concept of exposure for controlling the brightness of the resulting image, find the relationship

between exposure and the maximum radiance of the image and calculate an exposure compensated radiance value that

we can later map into the interval in the next

section.

Exposure is the amount of light per unit area reaching the sensor. A camera has the following parameters to control the exposure:

- Relative aperture (f-number, N) controls how wide the aperture is opened.

- Shutter time (t) controls how long the aperture is opened.

- Sensor sensitivity (S) controls how photons are counted on the digital camera.

From these parameters the Exposure value can be calculated.

If , we get , which can be calculated using the following formula:

Now that we have these quantities, we need to figure out the formula that directly tells us the relationship between radiance and this exposure value. This is where another quantity called luminous exposure comes into play. The following formula can be found on Wikipedia:

Where is the luminous exposure, is the luminance of the scene and is the lens and vignetting attenuation.

This luminance is an energy related physical quantity, but it is not a radiometric quantity but a photometric

quantity. Radiometry is a field of physics that deals

with measuring electromagnetic radiation in general.

Photometry on the other hand deals with measuring

light in terms of its perceived brightness to the human eye. Many of their physical quantities are analogous to

each other, but the units of measurement will be different. The

Moving Frostbite to PBR

document contains a table of radiometric and analogous photometric quantities in Table 5

of the Lighting

section.

The photometric analogy of radiant power is luminous power. Because of ambiguities radiant power did not meet our requirements and we discovered radiance. The same problem occurs with luminous power, and we need to find a related quantity, which is luminance. Just as raidance is radiant power per area per solid angle, luminance is luminous power per area per solid angle. It is the photometric analogy of radiance and we will find a mathematical connection between them.

Now that we can grasp what luminance is, let's keep going with the formulae until we find the connection we need! There is a luminous exposure level , which is the maximum possible luminous exposure that does not lead to a clipped or bloomed camera output. The following formula can be found on Wikipedia:

We can substitute the formula for .

Now we can reorganize to get the max luminance.

The Frostbite doc says that and is a good choice, so we have a direct relationship between and the maximum luminance. Luminance can be converted to radiance by dividing with the maximum spectral luminous efficacy, which is and now we have a relationship between radiance and the exposure value.

An exposure value can be calculated from the average luminance of the image as well. This can be useful for eye

adaptation, which we will do in a later chapter. I recommend

reading the A Physically Based Camera

section of

the Frostbite document

to learn more.

Tone mapping

After exposure correction we have a number which tells us how bright the pixel should be, but the swapchain image with our setup can only contain color components in the range. Tone mapping is the processing stage when we take the result of our rendering calculations, which fall in the range of , and map it to the range of .

We could just clamp the result of the exposure correction step, because the value 1 would match the maximum luminance our camera can detect, but if we plug it into some curve the resulting image may be more pleasing to the eye. You can find some useful curves on Wikipedia.

In this tutorial we use the ACES curve from Krzysztof Narkowicz's blog post.

Now the color value for each color component falls into the range of , but we are still not done, because the swapchain's color space determines the interpretation of the pixel, so we must make sure that the value we write will be interpreted as the right color.

Linear to sRGB conversion

Now that we have tonemapped RGB values that fall within the range of

, we need to make sure that we write values that will be

interpreted correctly. If the Swapchain image format is R8G8B8A8, then every color channel will be an integer value within

the range of , but the light intensity emitted by the

monitor may not correspond to these values linearly. This will be determined by the swapchain's color space, which is

set to VK_COLOR_SPACE_SRGB_NONLINEAR_KHR.

The rendering equation gave linear radiance values, and even after tone mapping there is a problem with them: many shades of grey cluster close to zero, and the mid-grey is very close to zero. In sRGB color space the mid-grey is placed in the middle of the interval, so the dark shades of grey are more spread out. This is a much better utilization of the interval, because more precision is used for the shades of grey between black and the middle-grey. More details on the sRGB color space can be found on Wikipedia.

In order to convert from linear radiance values to sRGB is to plug it into the so called sRGB curve.

The Frostbite document

mentions at the Color Space

section that there is an approximation to this curve, and warns against using it.

The correct curve is the following:

In this tutorial we will follow the recommendation and use the correct curve. Without transforming our tone mapped linear radiance value, the numbers we write to the swapchain image will be misinterpreted, and the whole image will be darker than it should be, so applying this function is necessary.

Now that we have covered all the theory we need, we can start figuring out our scene representation and get to coding.

Scene representation

In order to form images using the previously described method, we need to extend our scene representation to make sure it contains all the information our new formulae require. These will be surface normals, material data and light data.

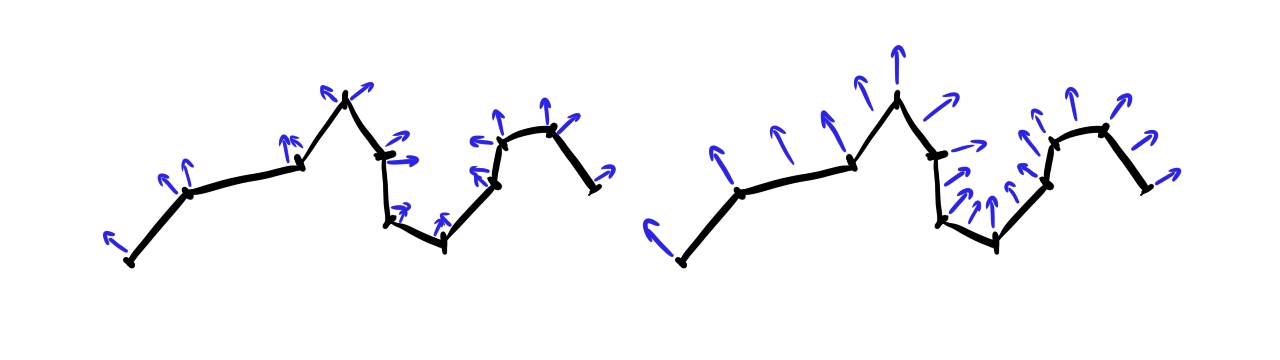

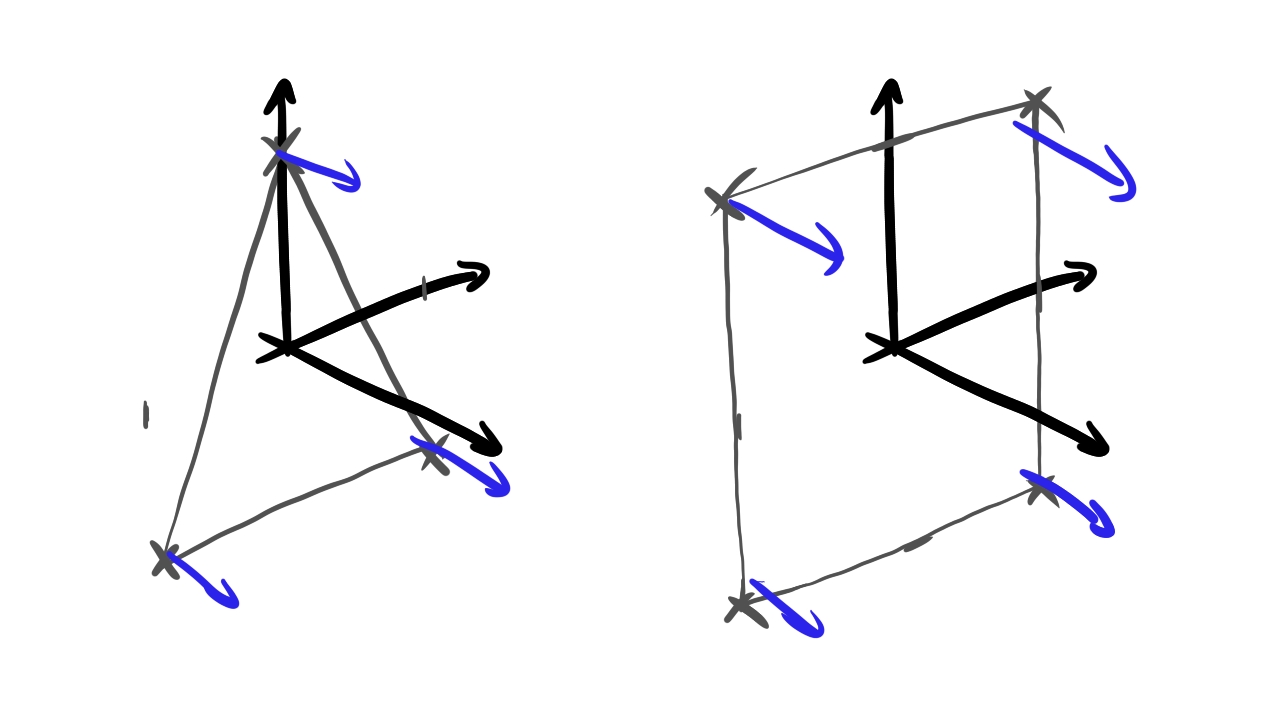

The rendering equation requires surface normals to determine the projected surface area, so we need to add normals to our models' vertex data. For the normal vectors in-between vertices we will interpolate the normals assigned to the triangle vertices. Notice that this is a bit of cheating, because a triangle is a flat surface, and the normal vectors should be the same across the whole triangle, but allowing different normal vectors for every vertex and smoothly interpolating them for lighting calculations can be exploited to give the illusion of smooth surfaces.

The rendering equation also depends on certain pieces of material data, so we need to add these to every scene object. Some of these are the parameters of the BRDF. In the case of the simple diffuse BRDF this is the probability of reflecting red, green and blue light, which will be three constants. We call these the albedo. Beyond these the material can emit light, and the parameters of this will be the emitted radiance for the red, green and blue components. We call this emissive light.

We will store the material data for every scene object separately. I chose this approach for this tutorial because it's simple and you have freedom in your game logic to continuously change a scene object's color if you want. For instance a scene objest's color can change from red to green, or from golden to silver continuously. The downside is the data duplication for scene objects that share the same material data, and the unnecessary data transfer for scene objects whose materials don't change. I chose this simple approach for learning, but you may want to implement something different in a real world application.

Finally we use the rendering equation to collect the radiance from direct illumination coming from a list of point lights, so we need to add these to the scene. They will be represented by their position in the scene, and the radiant intensity for the emitted red, green and blue light.

Now that we laid out what kind of data we need, we also need to talk about how this data will be processed. We will upload normals as vertex data, and it will be available in the vertex shader as an attribute. We will apply the necessary transformation and pass it to the fragment shader, just as we did with texture coordinates. Then the fragment shader will contain the implementation of the specialized rendering equation. It will have access to the normals passed from the vertex shader as an in variable, and it will need access to the material and light data to gather the radiance emitted and reflected by the surface element. After the radiance arriving at the camera at the given pixel is determined, we will apply exposure correction, tone mapping and sRGB conversion at the end of the fragment shader and write the results into the swapchain image.

Now that we have defined our tasks, it's time to start implementing them.

Adding normals to models

Data preparation

We need to add normals to our triangle and quad. These models are thin, and if you rotate the scene object, you will see its thin model from behind. We need to decide that one of its side is the front face, ant the other is the back face. The normal will point in the direction of the front face, and when the back face is seen, we just flip the normals. In this tutorial the front face will look at the positive Z direction in object space.

The new content of the array will be the following:

vec![

// Triangle

// Vertex 0

-1.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// Normal 0

0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

1.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// Normal 1

0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 1

1.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 2

0.0, 1.0, 0.0,

// Normal 2

0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 2

0.5, 1.0,

// Quad

// Vertex 0

-1.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// Normal 0

0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

1.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// Normal 1

0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 1

1.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 2

1.0, 1.0, 0.0,

// Normal 2

0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

-1.0, 1.0, 0.0,

// Normal 3

0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 3

0.0, 1.0

]

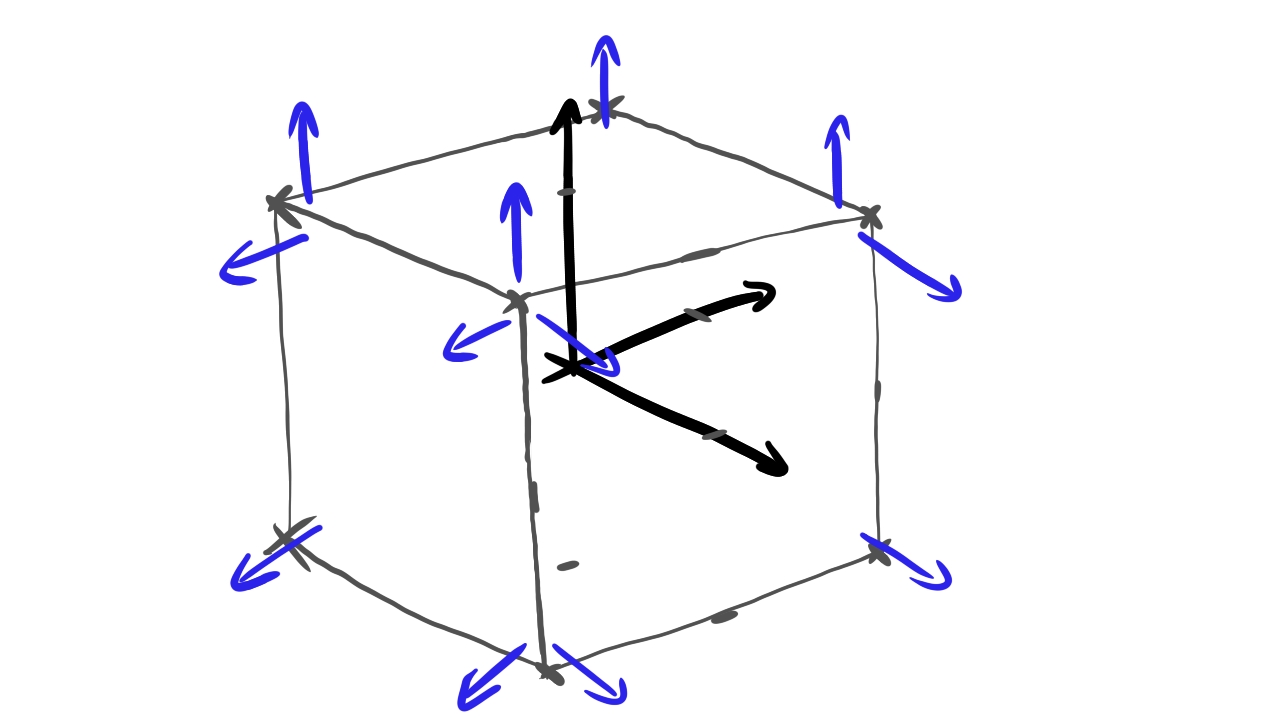

Now we need to add normals to the cube's faces. Every face of the cube will get a normal pointing outward from the center, perpendicular to the cube face.

The new content of the array will be the following:

vec![

// Pos Z

// Vertex 0

-0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 0

0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

-0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 1

0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 2

0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 3

0.0, 0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

// Neg Z

// Vertex 0

-0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 0

0.0, 0.0, -1.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

-0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 1

0.0, 0.0, -1.0,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 2

0.0, 0.0, -1.0,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 3

0.0, 0.0, -1.0,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

// Pos X

// Vertex 0

0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 0

1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 1

1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 2

1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 3

1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

// Neg X

// Vertex 0

-0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 0

-1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

-0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 1

-1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

-0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 2

-1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

-0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 3

-1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

// Pos Y

// Vertex 0

-0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 0

0.0, 1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

-0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 1

0.0, 1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, 0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 2

0.0, 1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

0.5, 0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 3

0.0, 1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

// Neg Y

// Vertex 0

-0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 0

0.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

-0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 1

0.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 1

0.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 2

0.5, -0.5, 0.5,

// Normal 2

0.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

0.5, -0.5, -0.5,

// Normal 3

0.0, -1.0, 0.0,

// TexCoord 3

1.0, 0.0,

]

Setting up the graphics pipeline

Now that we have set up the data for the normal vectors in the CPU side vertex data, it will be uploaded automatically, and the buffers will be sized correctly, but the shader needs to access the new data, just as it did with the texture coordinates.

For that we need to add the normal as a vertex attribute, just as we did with the texture coordinates.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let vertex_bindings = [

VkVertexInputBindingDescription {

binding: 0,

stride: 8 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>() as u32,

inputRate: VK_VERTEX_INPUT_RATE_VERTEX,

}

];

let vertex_attributes = [

VkVertexInputAttributeDescription {

location: 0,

binding: 0,

format: VK_FORMAT_R32G32B32_SFLOAT,

offset: 0,

},

VkVertexInputAttributeDescription {

location: 1,

binding: 0,

format: VK_FORMAT_R32G32B32_SFLOAT,

offset: 3 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>() as u32,

},

VkVertexInputAttributeDescription {

location: 2,

binding: 0,

format: VK_FORMAT_R32G32_SFLOAT,

offset: 6 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>() as u32,

}

];

let vertex_input_state = VkPipelineVertexInputStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_VERTEX_INPUT_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

vertexBindingDescriptionCount: vertex_bindings.len() as u32,

pVertexBindingDescriptions: vertex_bindings.as_ptr(),

vertexAttributeDescriptionCount: vertex_attributes.len() as u32,

pVertexAttributeDescriptions: vertex_attributes.as_ptr()

};

// ...

Pay attention that we reorganized our attributes a bit, now location 1 will belong to the normal, and the texture coordinates are moved to location 2.

The stride has also changed! We needed to add 3 floats per vertex to represent normals, and this needs to be reflected here. Previously it was 5 floats but now it's 8!

We calculate indexed draw call offsets using this stride where we define the draw call parameters of our models, so we need to update it there as well.

//

// Model and Texture ID-s

//

// ...

const PER_VERTEX_DATA_SIZE: usize = 8;

// ...

Now the draw call params for our models will be calculated correctly.

Adding material data and light array

The specialized version of the rendering equation requires material and light data, and if we want to run it on the GPU, then the GPU-side scene representation will need to store this new data. We will need to upload material and light data into uniform buffer regions. The material data will be placed in a tightly packed array separate from the transforms, because the fragment shader only needs the material data, and interleaving it with the transform data would be a waste of memory bandwidth. The light data will be stored in a third tightly packed array. We also need to upload a new variable for the exposure value.

To summarize, we will have the following uniform buffer regions:

- the transform array containing the camera data at the beginning and the model matrix array after

- the material array containing the exposure value at the beginning and the material data array after

- the light array containing the light count and the light data array

Let's start writing the code that defines our data structures!

UBO layout

First we look at the vertex shader UBO layout. We want a single per scene camera data and an array of model matrices. The data

structure from the previous tutorials will work fine, so we leave the memory layout unchanged.

We just rename ObjectData to TransformData, because now it only contains a piece of the "object data",

the object transform. The other piece is the material data, which will be in a different array accessible to the fragment shader.

Now that the "object data" is split in two, a more specific name is more fitting.

For the sake of completeness the shader code is the following:

struct CameraData

{

mat4 projection_matrix;

mat4 view_matrix;

};

struct TransformData

{

mat4 model_matrix;

};

const uint MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 8;

const uint MAX_OBJECT_COUNT = 64;

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 0) uniform UniformData {

CameraData cam_data;

TransformData transform_data[MAX_OBJECT_COUNT];

} uniform_transform_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

The renamed Rust struct matching the transform data is the following:

//

// Uniform data

//

// ...

#[repr(C, align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct TransformData

{

model_matrix: [f32; 16]

}

// ...

Then we define the structs of the material region as well, which will contain the per scene exposure settings and the per object

material data. We create the data structures ExposureData and MaterialData.

The shader code defining the material data is the following:

const uint MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 8;

const uint MAX_OBJECT_COUNT = 64;

struct MaterialData

{

vec4 albedo;

vec4 emissive;

};

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 2) uniform UniformMaterialData {

float exposure_value;

MaterialData material_data[MAX_OBJECT_COUNT];

} uniform_material_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

The matching Rust structs are the following:

//

// Uniform data

//

// ...

#[repr(C, align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct ExposureData

{

exposure_value: f32,

std140_padding_0: f32,

std140_padding_1: f32,

std140_padding_2: f32

}

#[repr(C, align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct MaterialData

{

albedo: [f32; 4],

emissive: [f32; 4]

}

// ...

The last region will be the light data where the per scene light count will be stored at the beginning, and per light data for

every light after. We create the data structures LightCountData and LightData.

The shader code for the light array is the following:

const uint MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 8;

const uint MAX_LIGHT_COUNT = 64;

struct LightData

{

vec4 position;

vec4 intensity;

};

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 3) uniform UniformLightData {

uint light_count;

LightData light_data[MAX_LIGHT_COUNT];

} uniform_light_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

The matching Rust structs are the following:

//

// Uniform data

//

// ...

#[repr(C, align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct LightCountData

{

light_count: u32,

std140_padding_0: f32,

std140_padding_1: f32,

std140_padding_2: f32,

}

#[repr(C, align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct LightData

{

position: [f32; 4],

intensity: [f32; 4]

}

// ...

Now that our data structures are defined properly, we need to size our buffer in a way that all three buffer range fits

into it, and can be accessed using UBO offsets. Offsets have alignment requirements: they must be aligned to

minUniformBufferOffsetAlignment. This means that we need to pad our uniform buffer regions to make sure

regions laid out one after another begin on an offset that is an integer multiple of

minUniformBufferOffsetAlignment.

//

// Uniform data

//

// ...

let min_ubo_offset_alignment = phys_device_properties.limits.minUniformBufferOffsetAlignment as usize;

let max_object_count = 64;

// Per frame UBO transform region size

let transform_data_size = core::mem::size_of::<CameraData>() + max_object_count * core::mem::size_of::<TransformData>();

let transform_data_align_rem = transform_data_size % min_ubo_offset_alignment;

let transform_data_padding;

if transform_data_align_rem != 0

{

transform_data_padding = min_ubo_offset_alignment - transform_data_align_rem;

}

else

{

transform_data_padding = 0;

}

let padded_transform_data_size = transform_data_size + transform_data_padding;

First we determine the higher bound to the amount of scene elements to render, max_object_count, which

will be 64.

Then we start figuring out the transform region size for a single frame. The useful data will need

core::mem::size_of::<CameraData>() amount of space to store the camera data, and

max_object_count * core::mem::size_of::<TransformData>() amount of space to store the transforms

for every scene object. Since these structs are padded according to the std140 alignment rules, their simple sum will

yield the amount of space the useful data will require.

Then we need to see if the resulting size will satisfy the alignment requirements. We take the remainder with the required offset alignment, and if it's not zero, then we add enough bytes to round the region size to an integer multiple of the required offset alignment.

// Per frame UBO material region size

let material_data_size = core::mem::size_of::<ExposureData>() + max_object_count * core::mem::size_of::<MaterialData>();

let material_data_align_rem = material_data_size % min_ubo_offset_alignment;

let material_data_padding;

if material_data_align_rem != 0

{

material_data_padding = min_ubo_offset_alignment - material_data_align_rem;

}

else

{

material_data_padding = 0;

}

let padded_material_data_size = material_data_size + material_data_padding;

Calculating the material data size for a single frame follows the same principles, only this time the struct sizes are

core::mem::size_of::<ExposureData>() and core::mem::size_of::<MaterialData>().

let max_light_count = 64;

// Per frame UBO light region size

let light_data_size = core::mem::size_of::<LightCountData>() + max_light_count * core::mem::size_of::<LightData>();

let light_data_align_rem = light_data_size % min_ubo_offset_alignment;

let light_data_padding;

if light_data_align_rem != 0

{

light_data_padding = min_ubo_offset_alignment - light_data_align_rem;

}

else

{

light_data_padding = 0;

}

let padded_light_data_size = light_data_size + light_data_padding;

The same goes for the light region for a single frame, this time with the struct sizes

core::mem::size_of::<LightCountData>() and core::mem::size_of::<LightData>().

// Total UBO size

let total_transform_data_size = frame_count * padded_transform_data_size;

let total_material_data_size = frame_count * padded_material_data_size;

let total_light_data_size = frame_count * padded_light_data_size;

let uniform_buffer_size = total_transform_data_size + total_material_data_size + total_light_data_size;

// ...

Finally we need to figure out the memory requirements for every frame. First let's specify the memory arrangement! First we place the transform regions for every frame one after the other. Then the material data regions for every frame one after the other, and finally the light regions one after the other.

The memory requirements for the transform regions laid out like this is

frame_count * padded_transform_data_size, and the other regions are analogous. Then we sum up all of the

regions to get the total uniform buffer size.

Now it's time to update the descriptor set layout.

Setting up descriptor set layout

We want to access two new uniform buffer regions per frame, and this will require new uniform buffer bindings. We start with adding these to the descriptor set layout.

//

// Descriptor set layout

//

// ...

let layout_bindings = [

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding {

binding: 0,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

descriptorCount: max_ubo_descriptor_count,

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

pImmutableSamplers: core::ptr::null()

},

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding {

binding: 1,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER,

descriptorCount: max_tex2d_descriptor_count,

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

pImmutableSamplers: core::ptr::null()

},

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding {

binding: 2,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

descriptorCount: max_ubo_descriptor_count,

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

pImmutableSamplers: core::ptr::null()

},

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding {

binding: 3,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

descriptorCount: max_ubo_descriptor_count,

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

pImmutableSamplers: core::ptr::null()

}

];

// ...

We append two new uniform buffer bindings, binding 2 and 3. These will be available from the

VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT, and will contain max_ubo_descriptor_count descriptors, following

the descriptor array scheme first introduced in the

uniform buffer chapter.

Setting up pipeline layout

We will have two new uniform buffer bindings to the fragment shader, the material and light data regions. They will be descriptor arrays, one descriptor per frame, and the material data region contains an array with per scene object data. To index into these arrays, we will need the push constants previously only available in the vertex shader, so we need to adjust our push constant ranges.

//

// Pipeline layout

//

// ...

// Object ID + Frame ID

let vertex_push_constant_size = 2 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32;

// Object ID + Frame ID + Texture ID

let fragment_push_constant_size = 3 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32;

let push_constant_ranges = [

VkPushConstantRange {

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

offset: 0,

size: vertex_push_constant_size,

},

VkPushConstantRange {

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

offset: 0,

size: fragment_push_constant_size,

}

];

// ...

The fragment shader's push constant range now spans three integers, the object index, the frame index and the texture index, and starts at zero offset.

Setting up descriptor pool and descriptor set

Now it's time to update everything related to descriptor set pools and descriptor sets, including writing the descriptor sets.

First let's update the descriptor pool sizes! We added two new bindings, each containing

max_ubo_descriptor_count descriptors. That means we need three times the amount of uniform buffer descriptors

as before, so let's adjust those pool sizes!

//

// Descriptor pool & descriptor set

//

let pool_sizes = [

VkDescriptorPoolSize {

type_: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

descriptorCount: max_ubo_descriptor_count * 3

},

VkDescriptorPoolSize {

type_: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER,

descriptorCount: max_tex2d_descriptor_count

}

];

// ...

There. A factor of 3 in the uniform buffer pool size.

Now let's fill the descriptor set! This is one of the places where the decisions we made about the layout of uniform buffer regions start to matter, so pay attention! Here are the uniform buffer descriptor writes:

//

// Descriptor pool & descriptor set

//

// ...

// Writing UBO descriptors

let mut transform_ubo_descriptor_writes = Vec::with_capacity(max_ubo_descriptor_count as usize);

for i in 0..max_ubo_descriptor_count

{

let ubo_region_index = (frame_count - 1).min(i as usize);

transform_ubo_descriptor_writes.push(

VkDescriptorBufferInfo {

buffer: uniform_buffer,

offset: (

ubo_region_index * padded_transform_data_size

) as VkDeviceSize,

range: transform_data_size as VkDeviceSize

}

);

}

let mut material_ubo_descriptor_writes = Vec::with_capacity(max_ubo_descriptor_count as usize);

for i in 0..max_ubo_descriptor_count

{

let ubo_region_index = (frame_count - 1).min(i as usize);

material_ubo_descriptor_writes.push(

VkDescriptorBufferInfo {

buffer: uniform_buffer,

offset: (

total_transform_data_size +

ubo_region_index * padded_material_data_size

) as VkDeviceSize,

range: material_data_size as VkDeviceSize

}

);

}

let mut light_ubo_descriptor_writes = Vec::with_capacity(max_ubo_descriptor_count as usize);

for i in 0..max_ubo_descriptor_count

{

let ubo_region_index = (frame_count - 1).min(i as usize);

light_ubo_descriptor_writes.push(

VkDescriptorBufferInfo {

buffer: uniform_buffer,

offset: (

total_transform_data_size + total_material_data_size +

ubo_region_index * padded_light_data_size

) as VkDeviceSize,

range: light_data_size as VkDeviceSize

}

);

}

// ...

First we prepare the transform data descriptor writes. The first transform data region resides at the beginning of the

uniform buffer, and the rest of the regions are laid out one after the other. The first loop fills the transform descriptor

writes with the offsets starting at the beginning of the buffer, and in every iteration the offset is bumped by

padded_transform_data_size for every region.

Then we prepare material data descriptor writes. The material data regions reside after the transform

regions, so the offset of the material regions start at total_transform_data_size and the offsets are bumped

by padded_material_data_size.

Finally we fill the light data descriptor writes. They come after the material data regions, so the offset of the light

regions start at total_transform_data_size + total_material_data_size, and in every iteration the offset

increases by padded_light_data_size.

Now that we prepared the descriptor writes, it's time to issue them.

//

// Descriptor pool & descriptor set

//

// ...

let descriptor_set_writes = [

VkWriteDescriptorSet {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_WRITE_DESCRIPTOR_SET,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

dstSet: descriptor_set,

dstBinding: 0,

dstArrayElement: 0,

descriptorCount: transform_ubo_descriptor_writes.len() as u32,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

pImageInfo: core::ptr::null(),

pBufferInfo: transform_ubo_descriptor_writes.as_ptr(),

pTexelBufferView: core::ptr::null()

},

VkWriteDescriptorSet {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_WRITE_DESCRIPTOR_SET,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

dstSet: descriptor_set,

dstBinding: 1,

dstArrayElement: 0,

descriptorCount: tex2d_descriptor_writes.len() as u32,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER,

pImageInfo: tex2d_descriptor_writes.as_ptr(),

pBufferInfo: core::ptr::null(),

pTexelBufferView: core::ptr::null()

},

VkWriteDescriptorSet {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_WRITE_DESCRIPTOR_SET,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

dstSet: descriptor_set,

dstBinding: 2,

dstArrayElement: 0,

descriptorCount: material_ubo_descriptor_writes.len() as u32,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

pImageInfo: core::ptr::null(),

pBufferInfo: material_ubo_descriptor_writes.as_ptr(),

pTexelBufferView: core::ptr::null()

},

VkWriteDescriptorSet {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_WRITE_DESCRIPTOR_SET,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

dstSet: descriptor_set,

dstBinding: 3,

dstArrayElement: 0,

descriptorCount: light_ubo_descriptor_writes.len() as u32,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

pImageInfo: core::ptr::null(),

pBufferInfo: light_ubo_descriptor_writes.as_ptr(),

pTexelBufferView: core::ptr::null()

}

];

// ...

We adjusted the previous tutorials' uniform upload struct for the transform data, adjusting it to take

transform_ubo_descriptor_writes as a parameter, and we add two new descriptor writes, one taking

light_ubo_descriptor_writes and another taking material_ubo_descriptor_writes as a parameter.

This takes care of the descriptor writes of the new uniform buffer regions.

CPU side scene representation

In the 3D tutorial we have created a StaticMesh struct which maintained the scene's CPU side state. Previously

it only contained transform data. Now that the rendering equation requires additional data, we must extend our

StaticMesh data structure to contain material data. We need to add the constant parameters for the diffuse

BRDF and the emissive lighting, so let's add those new fields!

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

struct StaticMesh

{

x: f32,

y: f32,

z: f32,

scale: f32,

rot_x: f32,

rot_y: f32,

albedo_r: f32,

albedo_g: f32,

albedo_b: f32,

emissive_r: f32,

emissive_g: f32,

emissive_b: f32,

texture_index: u32,

model_index: usize

}

// ...

We added three new albedo fields, one for each color channel, which will contain the diffuse BRDF parameters for each corresponding wavelength. We also added three emissive fields, one for each color channel, which will contain the emitted radiance for each color channel.

The rendering equation also requires lights, so we add a whole new type of scene elements, lights. We need to store their position and radiant intensity for every wavelength.

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

struct Light

{

x: f32,

y: f32,

z: f32,

intensity_r: f32,

intensity_g: f32,

intensity_b: f32

}

// ...

We have created our new struct, Light, and it has the x, y and z fields

to store the position, and the intensity fields to store the radiant intensity for every color channel.

Now that we have updated our scene data structures, let's fill the new fields for our scene elements.

First let's add a float for exposure correction! We will use this as exposure value during the exposure correction step, and we will be able to adjust it using the keyboard.

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

let mut exposure_value = 9.0;

// ...

Our variable will be exposure_value and by default we set it to 9.0, which is a value I stole

from wikipedia. There is a table of exposure values for various

lighting conditions, and 9 is the value for Neon and other bright signs

. The scene I am about to include will look

fine with this default exposure value, but we will increase and decrease it using the keyboard later.

As for the scene objects, we need to add material data. For the sake of simplicity, I'm just inlining the whole scene right here instead of only including the material data. It's simpler to copy paste this way.

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

let player_id = 0;

let mut static_meshes = Vec::with_capacity(max_object_count);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 0.25,

y: 0.0,

z: -1.25,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: triangle_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 0.25,

y: -0.25,

z: -2.0,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 0.75,

albedo_g: 0.5,

albedo_b: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: triangle_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -0.25,

y: 0.25,

z: -3.0,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 0.75,

albedo_g: 0.5,

albedo_b: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: quad_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 1.5,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.6,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: quad_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -1.5,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.6,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: quad_index

}

);

// Cubes added later

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 1.0,

y: 0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 1.0,

y: -0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -1.0,

y: 0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -1.0,

y: -0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

// ...

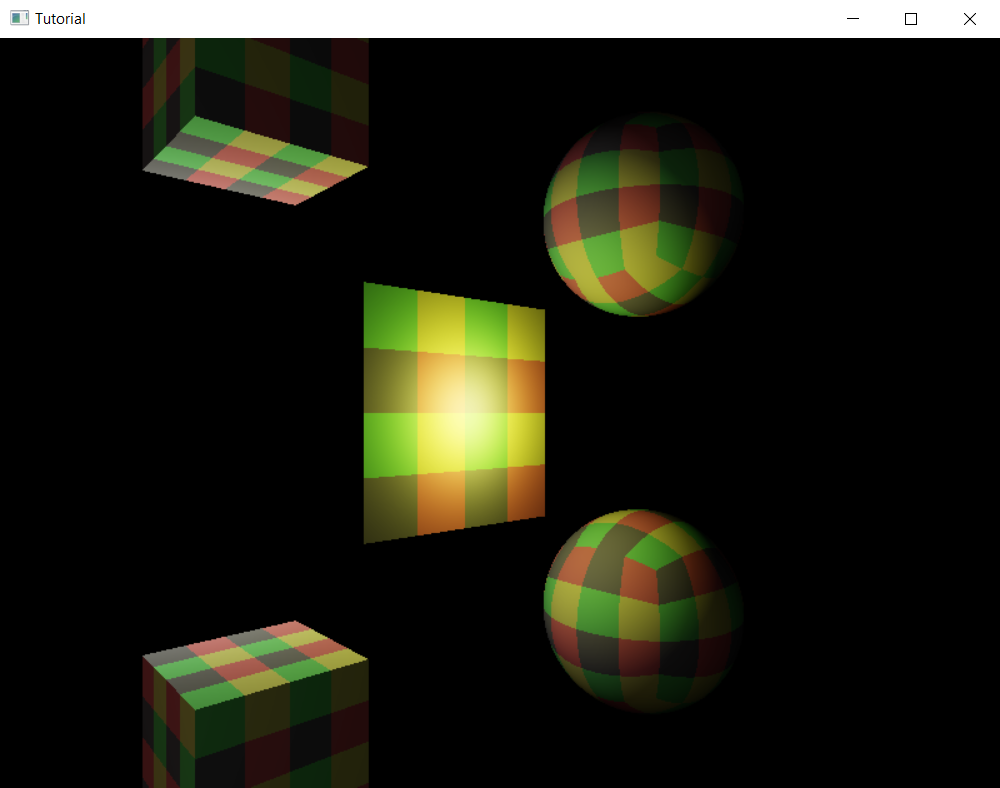

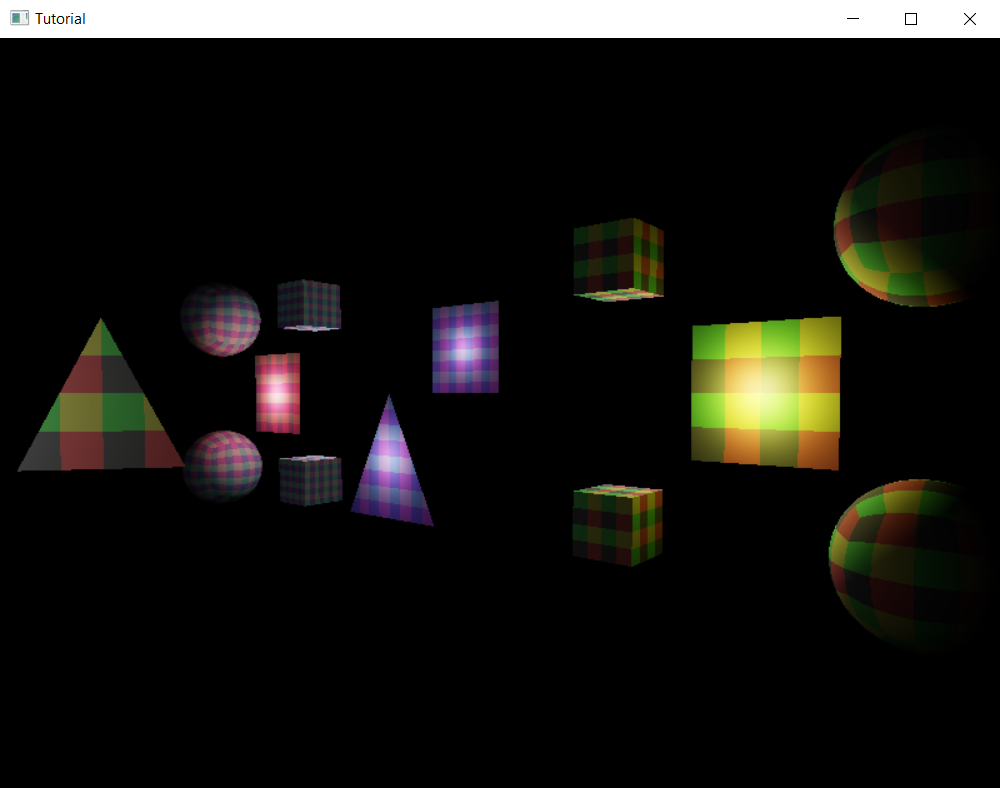

These are the models from the previous tutorial with some material data assigned to them.

Finally we add lights. I will add the following light sources:

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

let mut lights = Vec::with_capacity(max_light_count);

lights.push(

Light {

x: 0.0,

y: 0.0,

z: 0.0,

intensity_r: 0.5,

intensity_g: 0.5,

intensity_b: 0.5

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: 0.25,

y: -0.25,

z: -1.9,

intensity_r: 0.025,

intensity_g: 0.025,

intensity_b: 0.025

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: -0.25,

y: 0.25,

z: -2.9,

intensity_r: 0.025,

intensity_g: 0.025,

intensity_b: 0.025

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: 1.5,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.5,

intensity_r: 0.125,

intensity_g: 0.125,

intensity_b: 0.025

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: -1.5,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.5,

intensity_r: 0.125,

intensity_g: 0.025,

intensity_b: 0.025

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: -1.0,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.9,

intensity_r: 0.25,

intensity_g: 0.25,

intensity_b: 0.25

}

);

lights.push(

Light {

x: 1.0,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.9,

intensity_r: 0.25,

intensity_g: 0.25,

intensity_b: 0.25

}

);

// ...

Now that we have a basic game state, let's update our logic to update it using the keyboard!

Controlling exposure from keyboard

We want to control the exposure value using the keyboard. As with every other key from before, we need to remember if the key is pressed. For this we need a few new booleans.

//

// Game state

//

// Input state

// ...

let mut exposure_increase = false;

let mut exposure_decrease = false;

The exposure_increase will contain whether we hold the button we assign to increasing the exposure value, and

the exposure_decrease will contain whether we hold the decrease button.

Now let's update them when the right key events arrive!

//

// Game loop

//

// ...

let mut event_pump = sdl.event_pump().unwrap();

'main: loop

{

for event in event_pump.poll_iter()

{

match event

{

sdl2::event::Event::Quit { .. } =>

{

break 'main;

}

sdl2::event::Event::Window { win_event, .. } =>

{

// ...

}

sdl2::event::Event::KeyDown { keycode: Some(keycode), .. } =>

{

// ...

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::Y

{

exposure_increase = true;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::X

{

exposure_decrease = true;

}

}

sdl2::event::Event::KeyUp { keycode: Some(keycode), .. } =>

{

// ...

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::Y

{

exposure_increase = false;

}

if keycode == sdl2::keyboard::Keycode::X

{

exposure_decrease = false;

}

}

_ =>

{}

}

}

// ...

}

I assigned the Y button to increasing, and the X button to decreasing the exposure value. If you are using a non-QWERTZ keyboard, you probably want to assign it differently.

Now that we know whether the exposure increase or exposure decrease buttons are held, let's handle it in the game logic!

//

// Logic

//

// ...

if exposure_increase

{

exposure_value += 0.1;

}

if exposure_decrease

{

exposure_value -= 0.1;

}

If the exposure increase button is held, we add to the exposure value in every frame, and if the exposure decrease button is held, then we subtract from it.

Now it's time to upload our new data to the GPU.Data upload

We have new uniform buffer regions to fill, and we have extended our game state to serve as a data source, so it's time to update our upload logic.

First let's create struct references and slices to the uniform buffer regions!

//

// Rendering

//

//

// Uniform upload

//

{

// Getting references

let current_frame_transform_region_offset = (

current_frame_index * padded_transform_data_size

) as isize;

let camera_data;

let transform_data_array;

unsafe {

let per_frame_transform_region_begin = uniform_buffer_ptr.offset(

current_frame_transform_region_offset

);

let camera_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<CameraData> = core::mem::transmute(

per_frame_transform_region_begin

);

camera_data = &mut *camera_data_ptr;

let transform_offset = core::mem::size_of::<CameraData>() as isize;

let transform_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<TransformData> = core::mem::transmute(

per_frame_transform_region_begin.offset(transform_offset)

);

transform_data_array = core::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(

transform_data_ptr,

max_object_count

);

}

let current_frame_material_region_offset = (

total_transform_data_size +

current_frame_index * padded_material_data_size

) as isize;

let exposure_data;

let material_data_array;

unsafe {

let per_frame_material_region_begin = uniform_buffer_ptr.offset(

current_frame_material_region_offset

);

let exposure_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<ExposureData> = core::mem::transmute(

per_frame_material_region_begin

);

exposure_data = &mut *exposure_data_ptr;

let material_offset = core::mem::size_of::<ExposureData>() as isize;

let material_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<MaterialData> = core::mem::transmute(

per_frame_material_region_begin.offset(material_offset)

);

material_data_array = core::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(

material_data_ptr,

max_object_count

);

}

let current_frame_light_region_offset = (

total_transform_data_size + total_material_data_size +

current_frame_index * padded_light_data_size

) as isize;

let light_count_data;

let light_data_array;

unsafe {

let per_frame_light_region_begin = uniform_buffer_ptr.offset(

current_frame_light_region_offset

);

let light_count_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<LightCountData> = core::mem::transmute(

per_frame_light_region_begin

);

light_count_data = &mut *light_count_data_ptr;

let light_offset = core::mem::size_of::<LightCountData>() as isize;

let light_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<LightData> = core::mem::transmute(

per_frame_light_region_begin.offset(light_offset)

);

light_data_array = core::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(

light_data_ptr,

max_light_count

);

}

// ...

}

// ...

For every region we need to find the offset first. Pay attention that this follows the formulae we used during the

descriptor writes. The transform regions lie at the beginning of the uniform buffer, so the region of the current frame

is just current_frame_index * padded_transform_data_size. The material regions lie after all the transform

regions, so the material region of the current frame is at the offset

total_transform_data_size + current_frame_index * padded_material_data_size. Finally the lights lie after

all the material arrays, so their offset is at

total_transform_data_size + total_material_data_size + current_frame_index * padded_light_data_size.

Once we have the region offset, turning it into struct references and slices follows the same principles as the previous tutorials, only we have more of them.

Now let's adjust our existing upload logic! We have a new name for our transform array, and we need to update the transform upload accordingly.

//

// Rendering

//

//

// Uniform upload

//

{

// Getting references

// ...

// Filling them with data

let field_of_view_angle = core::f32::consts::PI / 3.0;

let aspect_ratio = width as f32 / height as f32;

let far = 100.0;

let near = 0.1;

let projection_matrix = perspective(

field_of_view_angle,

aspect_ratio,

far,

near

);

*camera_data = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

CameraData {

projection_matrix: mat_mlt(

&projection_matrix,

&scale(1.0, -1.0, -1.0)

),

view_matrix: mat_mlt(

&rotate_x(-camera.rot_x),

&mat_mlt(

&rotate_y(-camera.rot_y),

&translate(

-camera.x,

-camera.y,

-camera.z

)

)

)

}

);

let static_mesh_transform_data_array = &mut transform_data_array[..static_meshes.len()];

for (i, static_mesh) in static_meshes.iter().enumerate()

{

static_mesh_transform_data_array[i] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

TransformData {

model_matrix: mat_mlt(

&translate(

static_mesh.x,

static_mesh.y,

static_mesh.z

),

&mat_mlt(

&rotate_x(static_mesh.rot_x),

&mat_mlt(

&rotate_y(static_mesh.rot_y),

&scale(

static_mesh.scale,

static_mesh.scale,

static_mesh.scale

)

)

)

)

}

);

}

// ...

}

// ...

Instead of writing to the original object_data_array variable, we write to the new

transform_data_array, and we use the new struct name TransformData.

Now we start writing new upload code. We need to upload the new material data!

//

// Rendering

//

//

// Uniform upload

//

{

// Getting references

// ...

// Filling them with data

// ...

*exposure_data = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

ExposureData {

exposure_value: exposure_value,

std140_padding_0: 0.0,

std140_padding_1: 0.0,

std140_padding_2: 0.0

}

);

let static_mesh_material_data_array = &mut material_data_array[..static_meshes.len()];

for (i, static_mesh) in static_meshes.iter().enumerate()

{

static_mesh_material_data_array[i] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

MaterialData {

albedo: [

static_mesh.albedo_r,

static_mesh.albedo_g,

static_mesh.albedo_b,

0.0

],

emissive: [

static_mesh.emissive_r,

static_mesh.emissive_g,

static_mesh.emissive_b,

0.0

]

}

);

}

// ...

}

// ...

First we write the struct containing the exposure value to the beginning of the buffer region, then we iterate over every

scene object and write their material data to the material_data_array.

Finally we need to upload our light data.

//

// Rendering

//

//

// Uniform upload

//

{

// Getting references

// ...

// Filling them with data

// ...

*light_count_data = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

LightCountData {

light_count: lights.len() as u32,

std140_padding_0: 0.0,

std140_padding_1: 0.0,

std140_padding_2: 0.0

}

);

for (i, light) in lights.iter().enumerate()

{

light_data_array[i] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

LightData {

position: [

light.x,

light.y,

light.z,

0.0

],

intensity: [

light.intensity_r,

light.intensity_g,

light.intensity_b,

0.0

]

}

);

}

}

// ...

First we write the struct containing the light count to the light buffer region, then we iterate over every light and write their data into the light array.

Finally we have finished writing the uniform buffer upload. Now it's time to adjust command buffer recording!

Encoding command buffers

One of the first things we need to do is adjust the push constant upload. Previously the frame index and the object index were only used in the vertex shader, but we have adjusted the push constant ranges in the pipeline layout, and we will need them in the fragment shader. We will need the frame index to access the right material and light region, and we will need the object index to access the right material data, so let's add a few stage bits!

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

// ...

// Setting per frame descriptor array index

let ubo_desc_index: u32 = current_frame_index as u32;

vkCmdPushConstants(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

pipeline_layout,

(VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT | VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT) as VkShaderStageFlags, // We changed this

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

&ubo_desc_index as *const u32 as *const core::ffi::c_void

);

for (i, static_mesh) in static_meshes.iter().enumerate()

{

// Per obj array index

let object_index = i as u32;

vkCmdPushConstants(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

pipeline_layout,

(VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT | VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT) as VkShaderStageFlags, // We changed this

0,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

&object_index as *const u32 as *const core::ffi::c_void

);

// Setting texture descriptor array index

vkCmdPushConstants(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

pipeline_layout,

VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

2 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

&static_mesh.texture_index as *const u32 as *const core::ffi::c_void

);

vkCmdDrawIndexed(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

models[static_mesh.model_index].index_count,

1,

models[static_mesh.model_index].first_index,

models[static_mesh.model_index].vertex_offset,

0

);

}

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

Now we set the VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT as well when uploading these two push constants, because the new

push constant range in the pipeline layout now starts at offset 0, and includes these ranges as well.

Now we are pretty much done with the CPU side modifications, at least for the purpose of setting up diffuse lighting, so we can start writing our shaders.

Shader programming

Vertex shader

The rendering equation requires per pixel normals, and we provided the normals as vertex data. We need to transform these normals using the scene object's transform data and pass them to the fragment shader to be interpolated for the whole triangle and used in the rendering equation.

#version 460

struct CameraData

{

mat4 projection_matrix;

mat4 view_matrix;

};

struct TransformData

{

mat4 model_matrix;

};

const uint MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 8;

const uint MAX_OBJECT_COUNT = 64;

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 0) uniform UniformData {

CameraData cam_data;

TransformData transform_data[MAX_OBJECT_COUNT];

} uniform_transform_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

layout(push_constant) uniform ResourceIndices {

uint obj_index;

uint ubo_desc_index;

} resource_indices;

layout(location = 0) in vec3 position;

layout(location = 1) in vec3 normal;

layout(location = 2) in vec2 tex_coord;

layout(location = 0) out vec3 frag_position;

layout(location = 1) out vec3 frag_normal;

layout(location = 2) out vec2 frag_tex_coord;

void main()

{

uint ubo_desc_index = resource_indices.ubo_desc_index;

uint obj_index = resource_indices.obj_index;

mat4 model_matrix = uniform_transform_data[ubo_desc_index].transform_data[obj_index].model_matrix;

mat4 view_matrix = uniform_transform_data[ubo_desc_index].cam_data.view_matrix;

mat4 projection_matrix = uniform_transform_data[ubo_desc_index].cam_data.projection_matrix;

mat3 normal_matrix = inverse(transpose(mat3(model_matrix)));

mat4 mvp_matrix = projection_matrix * view_matrix * model_matrix;

frag_position = (model_matrix * vec4(position, 1.0)).xyz;

frag_normal = normal_matrix * normal;

frag_tex_coord = tex_coord;

gl_Position = mvp_matrix * vec4(position, 1.0);

}

There are cosmetic changes such as renaming uniform_data to uniform_transform_data, renaming

ObjectData to TransformData and renaming the field obj_data in the uniform buffer

to transform_data.

Then we start implementing features. We need to edit the vertex attributes to match what we defined in the graphics

pipeline. We moved the tex_coord to location 2 and we added a new one, normal

at location 1.

We also add new out variables, frag_position and frag_normal. The rendering

equation depends on the surface position and the normal, so we will supply it from the vertex shader.

Then we start transforming our normal and position.

Transforming the normal is a tricky one, because you cannot translate and scale it like you do with the position. Based on László Szirmay-Kalos' computer graphics video series we can learn how to transform surface normals. In this video at the timestamp he shows us how to transform a plane using a homogeneous matrix. We will adjust this proof to follow our conventions and also tweak it a bit.

The process is the following: let's construct a plane in the position of our vertices using the normal we passed as vertex data! A plane can be described by its normal vector and a point on the plane. Let the normal be and the point of the plane be ! Whether a point lies on the plane is determined by whether the following equation is true:

Which basically means whether the distance of along the normal is the same as the distance of

along the normal. By the way if we rename

to be

Now the plane is represented by four real numbers. We can further rearrange this using homogeneous coordinates, this way our equation will be in the same form as in the video, and we can finally start applying its logical steps. Let's name the components of and the following way!

Now we can write down the plane equation with homogeneous coordinates. Let's redefine as the point's homogeneous coordinates, and let's create a new homogeneous normal vector whose first three coordinates are the normal vector's coordinates, and the fourth component is the previously introduced . Now the equation will look like this:

So it's now basically a dot product. If and are represented by single column matrices, then the dot product can be expressed by a matrix multiplication. The T in the normal vector's upper index denotes the transpose of a matrix. This operation flips a matrix over its diagonal. Check wikipedia for details, we cannot cover every related rule that we will use! Transposing a column vector turns it into a row vector, and using matrix multiplication on a column and a row vector in the way we did in the previous equation results in a dot product. Transposing the normal will be important for many of the coming rearrangements.

Now we can do everything László Szirmay-Kalos does in the video to find the transformation of the normal: let a new be a point in homogeneous coordinates! If we applied a homogeneous linear transformation represented by the 4x4 matrix , the new would be...

Now we can write down in terms of like this:

Where is the inverse matrix of . The inverse matrix of is the matrix for which the following equation is true:

Where is the identity matrix.

We can substitute the previous equation for P into the homogeneous plane equation.

We finally have an equation with the normal vector and a transformation matrix in it! We even grouped them together! Now first let's remember that in the original plane equation the transpose of a column normal is matrix multiplied with the column vector representing a point! Then let's see if we can re-label the normal multiplied by the inverse transform matrix in a way that the equation will be of the same form! Let's do a bit of rearrangement using some of the properties of transposing found on wikipedia...

We now have a new transformed normal vector. Plugging the transpose of back into the plane equation we can rearrange it to be...

This is a plane equation with the transformed normal. We can see that is what we were looking for. Basically we have found that if we want to transform a plane, we can transform its normal by multiplying it with the inverse transpose of the transformation.

We can hack the system a bit and say that actually we only want to transform the three coordinate normals, and

we do not want to translate it, so we can take the 3x3 submatrix of the transformation matrix, which does not translate,

and only invert and transpose that one. This way we get the so called normal_matrix, which is

inverse(transpose(mat3(model_matrix))). If we multiply the normal vector from the left, we get the transformed

normal vector in world space.

This was a lot.

For transforming the position conceptually we do the same as we did before, multiply with the model, view and projection

matrix, but instead of doing that one by one, we just pre-multiply them and store them in the mvp_matrix.

The remaining part of the shader is much simpler to comprehend. We will perform the rendering equation in world space,

so we pass the world space transformed position and normal to the fragment shader, and finally we calculate the value

of gl_Position as well, by multiplying the vertex position by the concatenated model, view and projection

matrix.