Depth buffer

In the previous chapter we specified the problem of projecting the 3D images to our 2D screen, studied a bit of linear algebra, and learned a few basic transformations. We also learned about homogeneous coordinates, central projection, and constructed a projection matrix which can solve our problem.

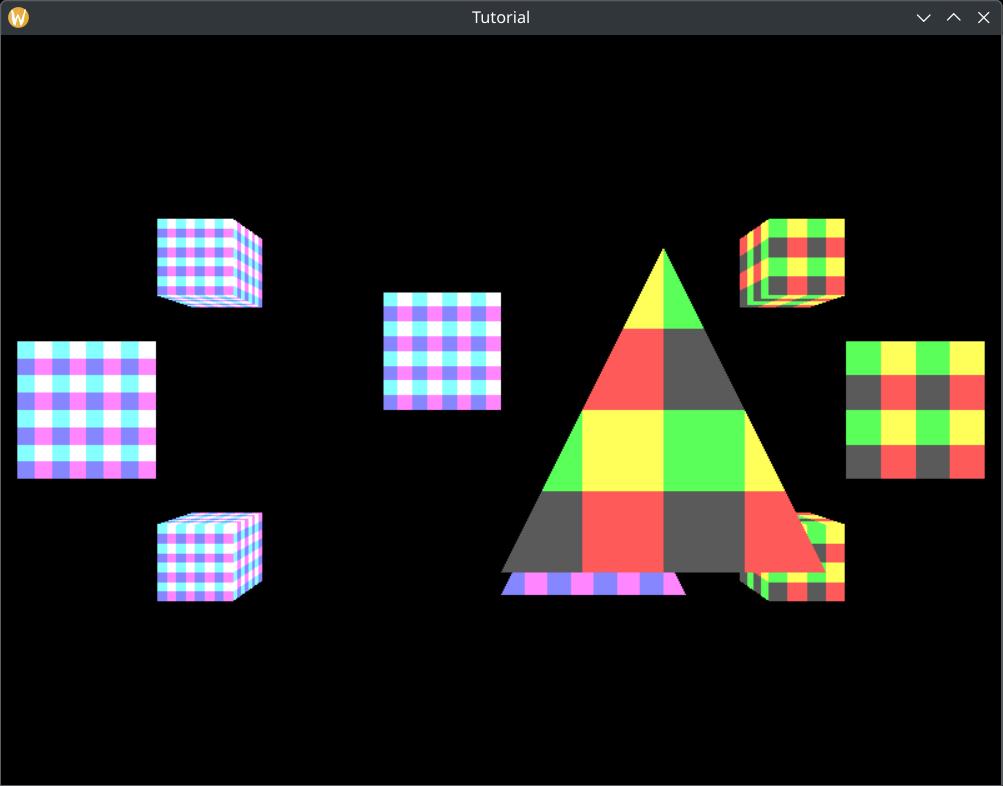

At the end of the chapter however our application had artifacts introducing a new problem: the order of rendering triangles matters, and this order dependency ruined the looks of our 3D application.

In this chapter we will learn the go-to solution to this problem: depth testing.

As long as your scene elements are opaque, you can create a second texture, a depth buffer. Then we calculate a z coordinate for the fragment, and if the new z coordinate is farther away than the current depth buffer contents, we discard it. If it is closer, then we overwrite the color and the depth buffer content at that pixel. This way only the triangles that are not occluded will be visible.

Our current projection matrix does not produce a proper Z coordinate, so we will need to extend it to finally match the one found in the literature. This will involve a bit of equation solving.

There will be a bit of math in this chapter as well. The advice from the previous tutorials holds: you can understand math in many ways, depending on your way of thinking and background:

- Read and understand the math first, then the code

- Understand the code first, and then interpret the math

Read whichever way is better for you. Be prepared that multiple rereads may be necessary.

This tutorial is in open beta. There may be bugs in the code and misinformation and inaccuracies in the text. If you find any, feel free to open a ticket on the repo of the code samples.

Depth buffering

A depth buffer is an image of the same size as our color attachment, but instead of containing color, it contains depth information. Graphics pipelines can be configured to take advantage of a depth buffer. For instance with the right configuration it can reject fragments that would be occluded by an already rendered model.

We need to perform the following steps to use a depth buffer:

- We need meaningful depth information, and for this we need to adjust our projection matrix.

- We need an image that is usable as a depth buffer.

- We need to adjust our render pass, framebuffer and pipeline to utilize our depth buffer.

- We need to clear not only the color attachment but the depth attachment as well.

Adjusting projection matrix

The depth buffer will be filled with the gl_Position.z coordinate after the homogeneous division.

Let this coordinate be !

We want to map this coordinate into the range of . We do this by multiplying the view space coordinate with a constant and add a constant to it.

If we multiply the view space vector with this projection matrix from the left, the projected z coordinate will be...

After homogeneous division the resulting z coordinate will be...

Let the near plane distance be and the far plane distance be ! For we want to be 0, and for we want to be 1. We substitute these two edge cases, and solve the equations.

Let's solve these equations! By rearranging equation 1 we get...

Substituting into equation 2 we get...

Rearranging this will result in...

From this can be expressed as...

Substituting into equation 1 we get

We can cancel out , so we can get something like this...

From this can be expressed...

Now we have an and a as the function of parameters and . Substituting and into the matrix we get...

This matrix will give us z coordinates usable with a depth buffer.

The perspective function calculating this matrix will be:

//

// Math

//

// ...

fn perspective(field_of_view_angle: f32, aspect_ratio: f32, far: f32, near: f32) -> [f32; 16]

{

let tan_fov = (field_of_view_angle / 2.0).tan();

let m00 = 1.0 / (aspect_ratio * tan_fov);

let m11 = 1.0 / tan_fov;

let m22 = far / (far - near);

let m23 = far * near / (near - far);

[

m00, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, m11, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, 0.0, m22, 1.0,

0.0, 0.0, m23, 0.0

]

}

This matrix will finally be the same or at least as useful as the ones found in the literature. For instance there is a definition for the perspective matrix in Microsoft's docs that is essentially the same.

This matrix is finally complete! Now it's time to fill our uniform buffers with this matrix instead of the

shitty_perspective.

//

// Uniform upload

//

{

// Getting references

// ...

// Filling them with data

let field_of_view_angle = core::f32::consts::PI / 3.0;

let aspect_ratio = width as f32 / height as f32;

let far = 100.0;

let near = 0.1;

let projection_matrix = perspective(

field_of_view_angle,

aspect_ratio,

far,

near

);

*camera_data = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

CameraData {

projection_matrix: mat_mlt(

&projection_matrix,

&scale(1.0, -1.0, -1.0)

),

view_matrix: mat_mlt(

&rotate_x(-camera.rot_x),

&mat_mlt(

&rotate_y(-camera.rot_y),

&translate(

-camera.x,

-camera.y,

-camera.z

)

)

)

}

);

// ...

}

// ...

Using this matrix our vertex shaders will produce a usable z coordinate. Now let's start adapting our render pass to use a depth buffer.

Render pass setup

We need to add an extra attachment to the render pass and reference it as a depth attachment!

First let's add the depth attachment in the render pass creation logic.

//

// RenderPass creation

//

let mut attachment_descs = Vec::new();

// ...

let depth_attachment_description = VkAttachmentDescription {

flags: 0x0,

format: VK_FORMAT_D32_SFLOAT,

samples: VK_SAMPLE_COUNT_1_BIT,

loadOp: VK_ATTACHMENT_LOAD_OP_CLEAR,

storeOp: VK_ATTACHMENT_STORE_OP_DONT_CARE,

stencilLoadOp: VK_ATTACHMENT_LOAD_OP_DONT_CARE,

stencilStoreOp: VK_ATTACHMENT_STORE_OP_DONT_CARE,

initialLayout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_UNDEFINED,

finalLayout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_DEPTH_STENCIL_ATTACHMENT_OPTIMAL

};

attachment_descs.push(depth_attachment_description);

// ...

We have covered these fields during the clearing the screen chapter. Let's focus on how setting up the depth attachment is different.

First the format will not be some RGB or RGBA or any similar color format, but a depth format. In this tutorial

we choose VK_FORMAT_D32_SFLOAT.

The other thing that's different is the storeOp parameter. The color attachment had content that we

wanted to store after the render pass, because we wanted to present the image. Here we won't use the depth content

after rendering, so we can set it to VK_ATTACHMENT_STORE_OP_DONT_CARE.

Finally we want the image to be in a layout which is optimal for depth testing, so we set the

finalLayout to VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_DEPTH_STENCIL_ATTACHMENT_OPTIMAL.

Now that the attachment is properly specified, let's add an attachment reference to the subpass! We add a depth attachment reference the following way:

//

// RenderPass creation

//

// ...

let mut color_attachment_refs = Vec::new();

let new_attachment_ref = VkAttachmentReference {

attachment: 0,

layout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OPTIMAL

};

color_attachment_refs.push(new_attachment_ref);

let depth_attachment_ref = VkAttachmentReference {

attachment: 1,

layout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_DEPTH_STENCIL_ATTACHMENT_OPTIMAL

};

let mut subpass_descs = Vec::new();

let subpass_description = VkSubpassDescription {

flags: 0x0,

pipelineBindPoint: VK_PIPELINE_BIND_POINT_GRAPHICS,

inputAttachmentCount: 0,

pInputAttachments: core::ptr::null(),

colorAttachmentCount: color_attachment_refs.len() as u32,

pColorAttachments: color_attachment_refs.as_ptr(),

pResolveAttachments: core::ptr::null(),

pDepthStencilAttachment: &depth_attachment_ref, // We reference it here.

preserveAttachmentCount: 0,

pPreserveAttachments: core::ptr::null()

};

subpass_descs.push(subpass_description);

// ...

The newly added depth_attachment_ref will have its attachment field set to

1, because the second attachment is the depth attachment, and the layout to

VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_DEPTH_STENCIL_ATTACHMENT_OPTIMAL, because we want depth testing to be

as fast as possible.

We will pass this depth_attachment_ref to the subpass in the pDepthStencilAttachment

field.

With these two steps we have successfully adjusted the render pass.

Setting up depth buffers

Now it's time to create a depth image when we recreate the framebuffers. We will create and recreate them when we create or recreate our swapchain. It's going to be an attachment just like the color attachment, so we need an image and an image view.

Let's modify our framebuffer creation! We rename our create_framebuffers function to

create_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers and add a few parameters.

//

// Getting swapchain images and framebuffer creation with depth buffer

//

// We renamed create_framebuffers

unsafe fn create_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device: VkDevice,

chosen_phys_device: VkPhysicalDevice, // We added this

phys_device_mem_properties: &VkPhysicalDeviceMemoryProperties, // We added this

width: u32,

height: u32,

format: VkFormat,

render_pass: VkRenderPass,

swapchain: VkSwapchainKHR,

swapchain_imgs: &mut Vec<VkImage>,

swapchain_img_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

depth_buffers: &mut Vec<VkImage>, // We added this

depth_buffer_memories: &mut Vec<VkDeviceMemory>, // We added this

depth_buffer_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>, // We added this

framebuffers: &mut Vec<VkFramebuffer>

)

{

// Getting swapchain images

swapchain_img_views.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

for (i, swapchain_img) in swapchain_imgs.iter().enumerate()

{

// Creating swapchain image views...

}

depth_buffers.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

depth_buffer_memories.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

depth_buffer_views.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

for i in 0..swapchain_imgs.len()

{

// Creating depth image, memory and buffer view.

}

framebuffers.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

for (i, (swapchain_img_view, depth_buffer_view)) in swapchain_img_views.iter().zip(depth_buffer_views.iter()).enumerate()

{

// Creating framebuffers

}

}

We add chosen_phys_device to query format properties and phys_device_mem_properties

for image memory allocation.

We also add depth_buffers, depth_buffer_memories and depth_buffer_views

to store our depth image, its memory and its image view.

We also adjust our framebuffer destruction. We rename destroy_framebuffers to

destroy_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers and add a few parameters.

//

// Getting swapchain images and framebuffer creation with depth buffer

//

// ...

// We renamed destroy_framebuffers

unsafe fn destroy_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device: VkDevice,

swapchain_img_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

depth_buffers: &mut Vec<VkImage>, // We added this

depth_buffer_memories: &mut Vec<VkDeviceMemory>, // We added this

depth_buffer_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>, // We added this

framebuffers: &mut Vec<VkFramebuffer>

)

{

for swapchain_framebuffer in framebuffers.iter()

{

println!("Deleting framebuffer.");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyFramebuffer(

device,

*swapchain_framebuffer,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

}

framebuffers.clear();

//

// We will delete our depth buffer here.

//

for swapchain_img_view in swapchain_img_views.iter()

{

println!("Deleting swapchain image views.");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyImageView(

device,

*swapchain_img_view,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

}

swapchain_img_views.clear();

}

We will receive depth_buffers, depth_buffer_memories and depth_buffer_views

to delete it when the swapchain is recreated or the program quits.

Creating depth image

Now we write our actual depth image, allocate memory for it and create an image view.

We have already chosen our depth format to be VK_FORMAT_D32_SFLOAT, so let's see if this format

can be used as an optimally tiled depth attachment!

//

// Getting swapchain images and framebuffer creation with depth buffer

//

unsafe fn create_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device: VkDevice,

chosen_phys_device: VkPhysicalDevice,

phys_device_mem_properties: &VkPhysicalDeviceMemoryProperties,

width: u32,

height: u32,

format: VkFormat,

render_pass: VkRenderPass,

swapchain: VkSwapchainKHR,

swapchain_imgs: &mut Vec<VkImage>,

swapchain_img_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

depth_buffers: &mut Vec<VkImage>,

depth_buffer_memories: &mut Vec<VkDeviceMemory>,

depth_buffer_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

framebuffers: &mut Vec<VkFramebuffer>

)

{

// ...

let mut format_properties = VkFormatProperties::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetPhysicalDeviceFormatProperties(

chosen_phys_device,

VK_FORMAT_D32_SFLOAT,

&mut format_properties

);

}

if format_properties.optimalTilingFeatures & VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_DEPTH_STENCIL_ATTACHMENT_BIT as VkFormatFeatureFlags == 0

{

panic!("Image format VK_FORMAT_D32_SFLOAT with VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL does not support usage flags VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_DEPTH_STENCIL_ATTACHMENT_BIT.");

}

depth_buffers.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

depth_buffer_memories.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

depth_buffer_views.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

// ...

}

This is done the same way as checking the texture formats for optimally tiled sampled image usage, just this time with the depth attachment usage.

Then we start creating them. First we create the image for every frame, then allocate memory for every image and bind them. This is the same standard way as texture creation, there are only minor differences.

//

// Getting swapchain images and framebuffer creation with depth buffer

//

unsafe fn create_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device: VkDevice,

chosen_phys_device: VkPhysicalDevice,

phys_device_mem_properties: &VkPhysicalDeviceMemoryProperties,

width: u32,

height: u32,

format: VkFormat,

render_pass: VkRenderPass,

swapchain: VkSwapchainKHR,

swapchain_imgs: &mut Vec<VkImage>,

swapchain_img_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

depth_buffers: &mut Vec<VkImage>,

depth_buffer_memories: &mut Vec<VkDeviceMemory>,

depth_buffer_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

framebuffers: &mut Vec<VkFramebuffer>

)

{

// ...

depth_buffers.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

depth_buffer_memories.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

depth_buffer_views.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

for i in 0..swapchain_imgs.len()

{

let image_create_info = VkImageCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

imageType: VK_IMAGE_TYPE_2D,

format: VK_FORMAT_D32_SFLOAT,

extent: VkExtent3D {

width: width as u32,

height: height as u32,

depth: 1

},

mipLevels: 1,

arrayLayers: 1,

samples: VK_SAMPLE_COUNT_1_BIT,

tiling: VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL,

usage: VK_IMAGE_USAGE_DEPTH_STENCIL_ATTACHMENT_BIT as VkImageUsageFlags,

sharingMode: VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE,

queueFamilyIndexCount: 0,

pQueueFamilyIndices: core::ptr::null(),

initialLayout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_UNDEFINED

};

println!("Creating depth image.");

let mut depth_image = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateImage(

device,

&image_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut depth_image

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create depth image {}. Error: {}", i, result);

}

depth_buffers.push(depth_image);

let mut mem_requirements = VkMemoryRequirements::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetImageMemoryRequirements(

device,

depth_image,

&mut mem_requirements

);

}

let depth_buffer_mem_props = VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_DEVICE_LOCAL_BIT as VkMemoryPropertyFlags;

let mut chosen_memory_type = phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount;

for i in 0..phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

if mem_requirements.memoryTypeBits & (1 << i) != 0 &&

(phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypes[i as usize].propertyFlags & depth_buffer_mem_props) ==

depth_buffer_mem_props

{

chosen_memory_type = i;

break;

}

}

if chosen_memory_type == phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

panic!("Could not find memory type.");

}

let image_alloc_info = VkMemoryAllocateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_MEMORY_ALLOCATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

allocationSize: mem_requirements.size,

memoryTypeIndex: chosen_memory_type

};

println!("Depth image size: {}", mem_requirements.size);

println!("Depth image align: {}", mem_requirements.alignment);

println!("Allocating depth image memory");

let mut depth_image_memory = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkAllocateMemory(

device,

&image_alloc_info,

core::ptr::null(),

&mut depth_image_memory

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Could not allocate memory for depth image {}. Error: {}", i, result);

}

let result = unsafe

{

vkBindImageMemory(

device,

depth_image,

depth_image_memory,

0

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to bind memory to depth image {}. Error: {}", i, result);

}

depth_buffer_memories.push(depth_image_memory);

// ...

}

// ...

}

The main difference is the VK_FORMAT_D32_SFLOAT format and the

VK_IMAGE_USAGE_DEPTH_STENCIL_ATTACHMENT_BIT usage flag. The format is the same as the one we

selected during render pass creation, and the usage flag makes the image usable as a depth attachment.

Let's add cleanup code to the destroy_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers function!

//

// Getting swapchain images and framebuffer creation with depth buffer

//

// ...

unsafe fn destroy_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device: VkDevice,

swapchain_img_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

depth_buffers: &mut Vec<VkImage>,

depth_buffer_memories: &mut Vec<VkDeviceMemory>,

depth_buffer_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

framebuffers: &mut Vec<VkFramebuffer>

)

{

// ...

for depth_buffer in depth_buffers.iter()

{

println!("Deleting depth image");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyImage(

device,

*depth_buffer,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

}

depth_buffers.clear();

for depth_buffer_memory in depth_buffer_memories.iter()

{

println!("Deleting depth image device memory");

unsafe

{

vkFreeMemory(

device,

*depth_buffer_memory,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

}

depth_buffer_memories.clear();

// ...

}

// ...

Creating depth image view

Then we need to create an image view for our depth buffer, just as we needed to create one for our swapchain images.

//

// Getting swapchain images and framebuffer creation with depth buffer

//

unsafe fn create_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device: VkDevice,

chosen_phys_device: VkPhysicalDevice,

phys_device_mem_properties: &VkPhysicalDeviceMemoryProperties,

width: u32,

height: u32,

format: VkFormat,

render_pass: VkRenderPass,

swapchain: VkSwapchainKHR,

swapchain_imgs: &mut Vec<VkImage>,

swapchain_img_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

depth_buffers: &mut Vec<VkImage>,

depth_buffer_memories: &mut Vec<VkDeviceMemory>,

depth_buffer_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

framebuffers: &mut Vec<VkFramebuffer>

)

{

// ...

depth_buffers.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

depth_buffer_memories.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

depth_buffer_views.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

for i in 0..swapchain_imgs.len()

{

// ...

let image_view_create_info = VkImageViewCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_VIEW_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

image: depth_image,

viewType: VK_IMAGE_VIEW_TYPE_2D,

format: VK_FORMAT_D32_SFLOAT,

components: VkComponentMapping {

r: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

g: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

b: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

a: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY

},

subresourceRange: VkImageSubresourceRange {

aspectMask: VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_DEPTH_BIT as VkImageAspectFlags,

baseMipLevel: 0,

levelCount: 1,

baseArrayLayer: 0,

layerCount: 1

}

};

println!("Creating depth image view.");

let mut depth_image_view = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateImageView(

device,

&image_view_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut depth_image_view

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create depth image view {}. Error: {}", i, result);

}

depth_buffer_views.push(depth_image_view);

}

// ...

}

This one is again almost the same as the image view creation logic used for texture and swapchain image view creation with only a few differences.

First the format is set to VK_FORMAT_D32_SFLOAT to match the depth image's format and the format

set in the render pass.

The other one is the aspectMask. This time the aspectMask is

VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_DEPTH_BIT! Previously for textures and the swapchain images we just accepted that it

must be VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_COLOR_BIT. Now it is different, because our image is not a color image.

Pixels do not contain any kind of RGB or RGBA or any other kind of color. Now it contains depth information which

is a whole other thing. It may contain lots of extra data beyond the raw pixel data. This can build some

intuition for what the aspect of the image is, although it may still be vague for you.

The image views we have created must be destroyed when appropriate, so we add the cleanup functions to

destroy_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers.

//

// Getting swapchain images and framebuffer creation with depth buffer

//

// ...

unsafe fn destroy_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device: VkDevice,

swapchain_img_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

depth_buffers: &mut Vec<VkImage>,

depth_buffer_memories: &mut Vec<VkDeviceMemory>,

depth_buffer_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

framebuffers: &mut Vec<VkFramebuffer>

)

{

// ...

for depth_buffer_view in depth_buffer_views.iter()

{

println!("Deleting depth image views.");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyImageView(

device,

*depth_buffer_view,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

}

depth_buffer_views.clear();

// ...

}

// ...

There. The depth buffers and their image views are created and memory is allocated for them. Now we need to add it to the framebuffer.

Framebuffer setup

Now we need to add our depth buffer to the framebuffer. Remember that we added a second attachment to the render pass and our framebuffer attachments must match it. The first attachment was our color attachment, and the second attachment the depth attachment. Let's adjust our framebuffer creation logic accordingly!

//

// Getting swapchain images and framebuffer creation with depth buffer

//

unsafe fn create_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device: VkDevice,

chosen_phys_device: VkPhysicalDevice,

phys_device_mem_properties: &VkPhysicalDeviceMemoryProperties,

width: u32,

height: u32,

format: VkFormat,

render_pass: VkRenderPass,

swapchain: VkSwapchainKHR,

swapchain_imgs: &mut Vec<VkImage>,

swapchain_img_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

depth_buffers: &mut Vec<VkImage>,

depth_buffer_memories: &mut Vec<VkDeviceMemory>,

depth_buffer_views: &mut Vec<VkImageView>,

framebuffers: &mut Vec<VkFramebuffer>

)

{

// ...

framebuffers.reserve(swapchain_imgs.len());

for (i, (swapchain_img_view, depth_buffer_view)) in swapchain_img_views.iter().zip(depth_buffer_views.iter()).enumerate()

{

let attachments: [VkImageView; 2] = [

*swapchain_img_view,

*depth_buffer_view

];

let create_info = VkFramebufferCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_FRAMEBUFFER_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

renderPass: render_pass,

attachmentCount: attachments.len() as u32,

pAttachments: attachments.as_ptr(),

width: width,

height: height,

layers: 1

};

println!("Creating framebuffer.");

let mut new_framebuffer = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateFramebuffer(

device,

&create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut new_framebuffer

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create framebuffer {:?}. Error: {:?}.", i, result);

}

framebuffers.push(new_framebuffer);

}

}

In the for loop we zip the depth buffer views and the swapchain image views.

Then in the loop we add the depth buffer right after the swapchain image in the attachments

array. This will match our attachments in the render pass.

Adjusting call sites

The framebuffer creation and destruction function's name and arguments changed, so we must also adjust the places where they are called. One comes right after swapchain creation, another one is around swapchain recreation and one is at the final cleanup.

First let's adjust the initial creation!

//

// Getting swapchain images and framebuffer creation

//

let mut swapchain_imgs = Vec::new();

let mut swapchain_img_views = Vec::new();

let mut depth_buffers = Vec::new();

let mut depth_buffer_memories = Vec::new();

let mut depth_buffer_views = Vec::new();

let mut framebuffers = Vec::new();

unsafe

{

create_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device,

chosen_phys_device,

&phys_device_mem_properties,

width,

height,

format,

render_pass,

swapchain,

&mut swapchain_imgs,

&mut swapchain_img_views,

&mut depth_buffers,

&mut depth_buffer_memories,

&mut depth_buffer_views,

&mut framebuffers

);

}

// ...

Then let's adjust the final cleanup!

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

unsafe

{

destroy_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device,

&mut swapchain_img_views,

&mut depth_buffers,

&mut depth_buffer_memories,

&mut depth_buffer_views,

&mut framebuffers

);

}

// ...

Finally let's adjust swapchain recreation!

//

// Recreate swapchain if needed

//

if recreate_swapchain

{

// ...

unsafe

{

// This replaces destroy_framebuffers

destroy_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device,

&mut swapchain_img_views,

&mut depth_buffers,

&mut depth_buffer_memories,

&mut depth_buffer_views,

&mut framebuffers

);

}

// Swapchain recreation comes here...

unsafe

{

// This replaces create_framebuffers

create_framebuffers_and_depth_buffers(

device,

chosen_phys_device,

&phys_device_mem_properties,

width,

height,

format,

render_pass,

swapchain,

&mut swapchain_imgs,

&mut swapchain_img_views,

&mut depth_buffers,

&mut depth_buffer_memories,

&mut depth_buffer_views,

&mut framebuffers

);

}

// ...

}

// ...

Pipeline setup

The parameters of depth testing are part of the pipeline. We need to add a depth stencil state info to our pipeline creation.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let depth_stencil_state = VkPipelineDepthStencilStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_DEPTH_STENCIL_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

depthTestEnable: VK_TRUE,

depthWriteEnable: VK_TRUE,

depthCompareOp: VK_COMPARE_OP_LESS,

depthBoundsTestEnable: VK_FALSE,

stencilTestEnable: VK_FALSE,

front: VkStencilOpState {

failOp: VK_STENCIL_OP_KEEP,

passOp: VK_STENCIL_OP_KEEP,

depthFailOp: VK_STENCIL_OP_KEEP,

compareOp: VK_COMPARE_OP_NEVER,

compareMask: 0,

writeMask: 0,

reference: 0

},

back: VkStencilOpState {

failOp: VK_STENCIL_OP_KEEP,

passOp: VK_STENCIL_OP_KEEP,

depthFailOp: VK_STENCIL_OP_KEEP,

compareOp: VK_COMPARE_OP_NEVER,

compareMask: 0,

writeMask: 0,

reference: 0

},

minDepthBounds: 0.0,

maxDepthBounds: 1.0

};

// ...

The VkPipelineDepthStencilStateCreateInfo struct is enormous. Let's first focus on the fields that

are important right now!

First the field depthTestEnable determines whether the depth test is enabled or disabled. Setting

it to VK_TRUE enables depth testing. Then the field depthWriteEnable determines

whether writes to the depth attachment are allowed. If depth writes are enabled, the depth value of fragments

that are not rejected during depth testing will be written to the depth buffer. We set this to

VK_TRUE as well.

Now we need to set the parameters of depth testing. When we created our final projection matrix we decided that

the depth value of the near plane should be 0.0, and the depth value of the far plane should be 1.0. These

can be set with the parameters minDepthBounds and maxDepthBounds, which are set to

0.0 and 1.0 respectively.

Finally we want faces closer to the camera cover faces farther away, and the smaller the z coordinate, the

closer it is, so if the new depth value is less than the old one, our fragment must pass the depth

test. The field that sets this is depthCompareOp, and the value that does what we want is

VK_COMPARE_OP_LESS.

The rest are not important for us, and we just set them to zero, false, or some constant that has the integer value zero.

We have the depth stencil state info properly set up. We configured depth testing and disabled and did not talk about stencil. Just like every other pipeline state info we need to refer to this one as well during pipeline creation.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

// Creation

let pipeline_create_info = VkGraphicsPipelineCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_GRAPHICS_PIPELINE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

stageCount: shader_stage_info.len() as u32,

pStages: shader_stage_info.as_ptr(),

pVertexInputState: &vertex_input_state,

pInputAssemblyState: &input_assembly_state,

pTessellationState: core::ptr::null(),

pViewportState: &viewport_state,

pRasterizationState: &rasterization_state,

pMultisampleState: &multisample_state,

pDepthStencilState: &depth_stencil_state, // We reference it here.

pColorBlendState: &color_blend_state,

pDynamicState: &dynamic_state,

layout: pipeline_layout,

renderPass: render_pass,

subpass: 0,

basePipelineHandle: core::ptr::null_mut(),

basePipelineIndex: -1

};

// ...

In our VkGraphicsPipelineCreateInfo struct the field we must set is pDepthStencilState.

Clearing the depth buffer

Now we have one final step before we are done. When we begin our render pass during command buffer recording we must clear every attachment. We added a depth attachment, we need to clear that one as well.

//

// Rendering commands

//

let clear_value = [

VkClearValue {

color: VkClearColorValue {

float32: [0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

}

},

VkClearValue {

depthStencil: VkClearDepthStencilValue {

depth: 1.0,

stencil: 0

}

}

];

let render_pass_begin_info = VkRenderPassBeginInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_RENDER_PASS_BEGIN_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

renderPass: render_pass,

framebuffer: framebuffers[image_index as usize],

renderArea: VkRect2D {

offset: VkOffset2D {

x: 0,

y: 0

},

extent: VkExtent2D {

width: width,

height: height

}

},

clearValueCount: clear_value.len() as u32,

pClearValues: clear_value.as_ptr()

};

// ...

We add a new element to the clear_value array. In our VkClearValue union we need

to use the depthStencil variant, which is of the type VkClearDepthStencilValue.

We set the depth to 1.0, because that is the value of the far plane, and we don't

care about the stencil value.

...and that's it!

Now the player character, which is closer to the camera, cover things further away! Also the front faces of the cubes cover their back faces! We've done it!

Bonus: Depth testing and transparency

Back in the hardcoded triangle tutorial I already hinted at how much transparency sucks. Now you can piece together why.

Alpha blending is order dependent. The formula takes a weighted sum of the previous image content and the newly rendered triangle. Rendering triangles in a different order produces different results. Depending on how you define "transparent triangles" or "transparent scene objects", you may need to render triangles in the correct order, which may be front to back or back to front. Theoretically this could mean a separately sorted index buffer per model instance. Intersecting triangles would possibly need to be split.

The use of a depth buffer interacts with this problem. Since the opaque triangle that is closest to the camera must cover everything behind it, we use a depth buffer and write the depth of the closest triangle. If we encounter something further away, we discard it. This is not the case for transparent triangles. Naively enabling depth testing would introduce artifacts: some covered transparent triangles that are not the closest to the camera would be rendered, and some would be discarded by the depth testing.

Because of this many techniques were introduced that try to find some compromise between speed and correct transparency.

Alpha testing

If you can settle with a per pixel binary "opaque" vs "fully transparent" value with no semi-transparent value in-between, then you can use alpha testing. You can store transparency in a texture. Maybe in a separate transparency texture, maybe in the alpha channel.

In the fragment shader you sample this value at a texture coordinate. If the sampled value is "opaque", you continue running the fragment shader and write the opaque color value. If the value is "fully transparent", you make sure that neither the color nor the depth value gets written to attachments.

The method known to me is to use a keyword called discard in your fragment shader, and turn

off early Z testing.

This way you can render grasses, leaves, etc. as a quad, or a simple 2D geometry, define most of the shape of the grass, leaves, branches, etc. in the color and alpha values, and you don't have to create individual grass and leaf geometries.

If you do this, do proper research! Do not do it naively, because you can get a performance hit.

For instance with a depth prepass, you may only need to use discard during depth testing. Also if

you have to use discard in a fragment shader, create a separate alpha testing fragment shader and

a separate pipeline and only use it for the scene objects that actually need it. Draw the rest with a simple

opaque fragment shader and pipeline.

Rendering transparent models with depth testing

If you can settle with seeing only the front face of the closest transparent object, transparent objects occluding each other, and only letting opaque scene elements pass through them, you can render transparent objects with depth testing enabled into a different image, and combining the opaque and transparent images. If the depth buffer of the opaque image at a given pixel is further away than the transparent image's, then you alpha blend.

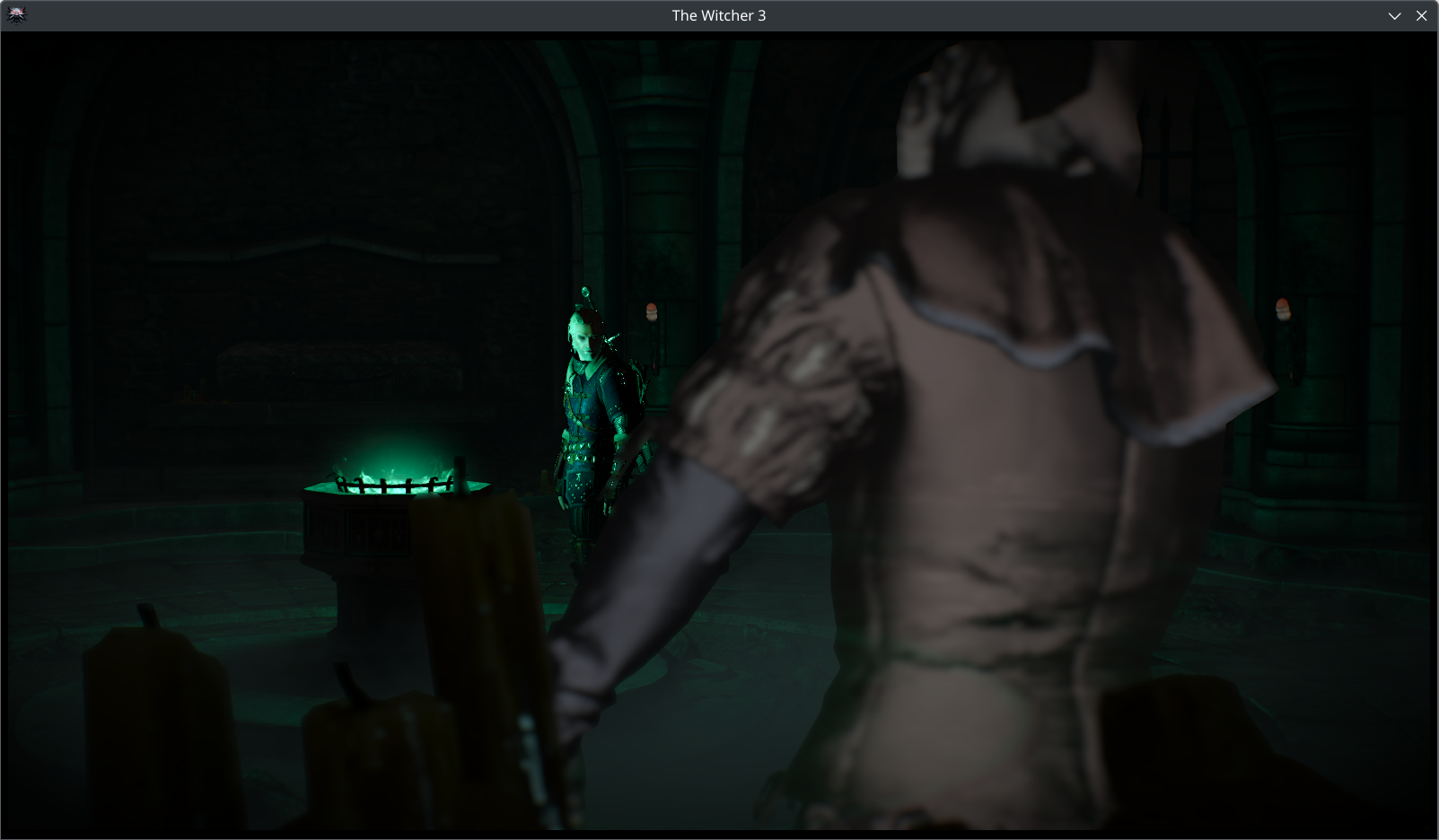

I suspect (although I haven't seen the code, nor did I capture a frame with renderdoc) that Mass Effect 1 and The Witcher 3 use something like this.

Let's see a few images from Mass Effect 1!

You can see the VI's body covering its arm, its chin covering its neck, the front of its head covering the back of its head, but the opaque background being partially visible.

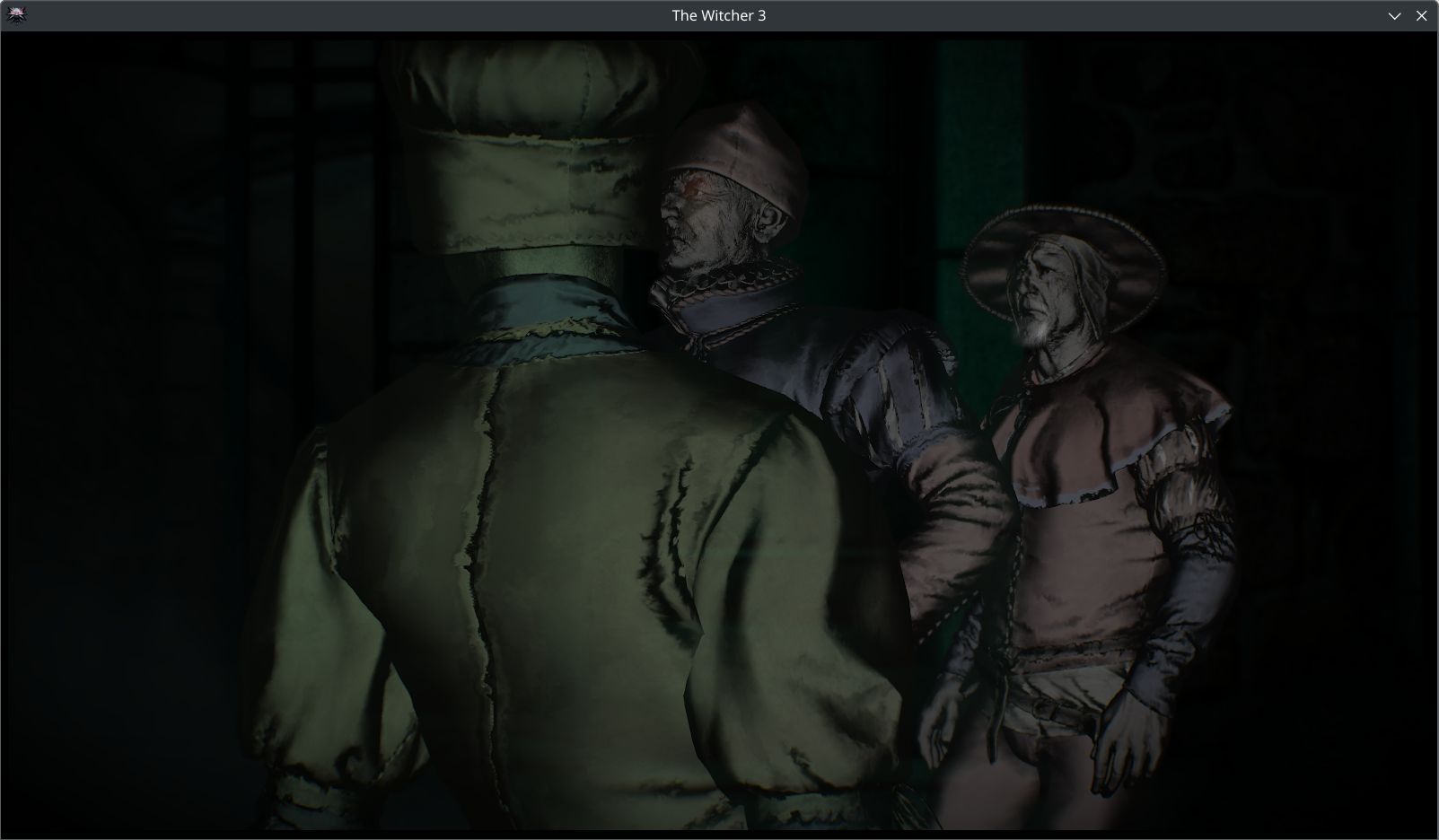

Now let's look at The Witcher 3!

On the first image the circular elements on the floor can be seen through the ghost's model, but only the back of the ghost is visible. On the second image you can clearly see that the ghosts are occluding each other, and no transparency is used between them.

Dithering

You can also render transparent objects with pixel sized holes between them, and hope that the resolution is big enough and the human eye will average them for you. The Witcher 3 probably uses something like this in some cases. Again, no renderdoc capture to confirm, just telling what I see.

The use of dithering is the most apparent on the first image, on Geralt's hair. It is also very apparent on the second image, on Geralt's neck.

Adrian Courréges also writes in his GTA 5 graphics study about checkerboard pattern being used for models in the background.

GPU sorting

Sometimes compromise is not good enough for you. In these cases you need to do what we really wanted to avoid: sort scene objects, and maybe even create sorted index buffers. Maybe you can get away with sorting a handful of scene objects on the CPU, but sorting many particles in a larger particle system or every transparent triangle on the CPU and uploading is going to be too slow.

When it is necessary, you can do GPU merge sorting with a compute shader, see Frostbite GPU Emitter Graph System and inFAMOUS™ Second Son Particle System Architecture.

Wrapping up

In this chapter we learned how to solve the final problem with 3D rendering: depth testing. We set up a depth buffer and adjusted our render pass, framebuffer, pipeline and rendering code to use it.

Now our application can finally render opaque 3D models correctly!

We also briefly touched on transparency techniques, compromises and a few useful resources.

The sample code for this tutorial can be found here.

This concludes the Vulkan basics tutorial. You can continue with the Physically Based Rendering tutorial. The tutorial continues here.