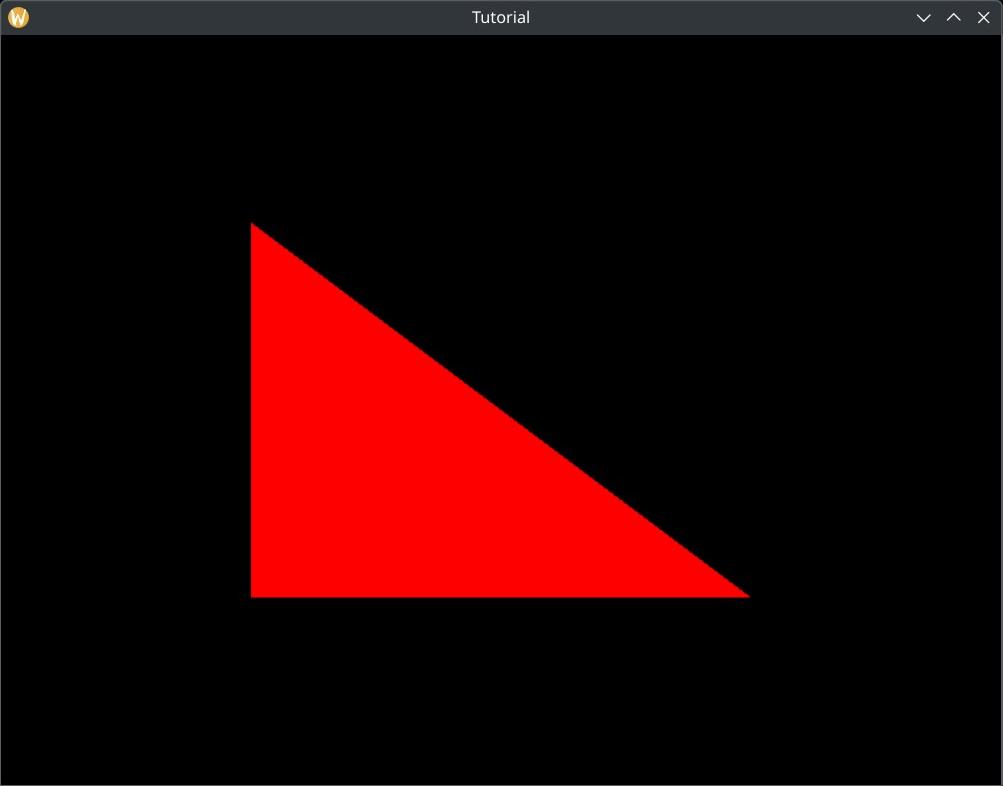

Hardcoded triangle

In the previous chapter we have taken a look at the details of the swapchain extension, made our window resizable and recreated the swapchain when we resized our window.

In this chapter we are going to learn about the graphics pipeline, configure its parameters, write our first shader, and render our first triangle.

This tutorial is in open beta. There may be bugs in the code and misinformation and inaccuracies in the text. If you find any, feel free to open a ticket on the repo of the code samples.

The graphics pipeline

Before we get into coding let's build a high level mental model of what the GPU does during rendering. Not a very detailed mental model, just enough to work with.

The GPU can draw triangles, line segments and points. These are called primitives. Our application must supply data defining triangles, line segments and points to the GPU, which is going to execute a multi step process to get these geometric primitives onto the screen.

Individual primitives can be defined by their vertices: a triangle can be defined by its three vertices, a line segment by its two verices and a point by its single vertex. A whole model can be made of primitives, so you can represent a model with a series of triangles, line segments or points.

Now we can piece together how we can render geometry: define it as a series of primitives, and feed it to the GPU, which execute its processes to render it to an image.

This was the bird view description. Let's get into some details and introduce some definitions!

The graphics pipeline is the multi step process that renders geometric primitives to the screen. Each step takes some input data, performs some operations on it and produces output data to be consumed by the next pipeline step.

Now we will briefly describe each step, their input and output data and how they are connected to form the whole pipeline. The simplified block diagram of the graphics pipeline can be seen in Figure 1. Note that this is a simplified model, advanced pipeline steps that we do not need yet will be skipped. These can be found in other literature, such as the spec.

The first operation of the graphics pipeline is input assembly. The input assembler is the pipeline step that supplies the primitives we want to draw, their type (triangles, lines or points) and a few other related parameters.

The next step is the vertex shader, which is a programmable step that calculates the position of every vertex on the screen. Conceptually it receives the vertices that define our primitives, performs operations on them (such as moving or rotating them), and feeds the result to the next step. This is a programmable step, meaning that the program that will calculate these vertex positions is written by a programmer and supplied to Vulkan by the application. The GPU runs executions of the vertex shader in parallel for many vertices and distributes them across many GPU cores.

Once the positions of vertices are calculated, the pixels covered by the primitive must be determined. The next step is the rasterizer, which determines which pixels of the image are covered by the primitives supplied by the previous step.

Once the covered pixels are determined, a color must be assigned to every pixel. The next step is the fragment shader which calculates the color of every individual covered pixel. This is also a programmable stage and the program is supplied by you. The executions of the fragment shader run in parallel for many pixels and get distributed across GPU cores.

After the colors are calculated, the color must be written to the image. The last step, color blending, will mix the newly calculated colors with the previous contents of the image. For instance, it can overwrite the previous color with the new colors, but it can also use alpha blending to calculate the weighted sum of the previous and new contents of the image to create the illusion of transparency.

Some of these steps are programmable, meaning that you write a program to tell them what they need to do. Some are fixed function, meaning that their mechanisms are roughly set in stone, but you can supply parameters for limited customization.

This summarizes the steps required to get triangles onto the screen. Now that you have the theory, it's time to define our scope.

We are going to extend our application to draw a single triangle. For the sake of simplicity we will hardcode the position of the triangle's vertices into the vertex shader, and will paint it in red in the fragment shader. This way we can get an instant result and defer getting familiar with an enormous amount of extra API later. This scope is inspired by the Graphics pipeline basics chapter of Alexander Overvoorde's Vulkan tutorial.

Now it's time to put together an actionable plan on how we are going to execute.

- We had two programmable steps in the graphics pipeline, and we need to write GPU programs for them, so we will write two shaders.

- Then we are going to compile and load these shaders into our application.

- Then we will collect all of the GPU programs and the parameters of the non programmable steps, and combine them into a Vulkan object that will represent the configuration of the graphics pipeline.

- Finally during rendering command recording we will apply the previously defined configuration and issue a draw call, executing the steps of the graphics pipeline and rendering to the swapchain images.

Now that we have a plan, let's start with shader writing!

Shaders

Now it's time to get into shader coding. Vulkan can consume shaders in the SPIR-V binary format. Only mazochists write SPIR-V by hand. What you want to do instead at least as a beginner, is to get a high level shader language, write your code in it and compile it into SPIR-V.

My choice is GLSL, because it has a specification, a gigantic amount of documentation and learning material, such as many stackoverflow questions and answers and the GLSL wiki of Khronos Group, the compiler can be cloned from git and be compiled fast, works out of the box on many OSes and it's easy to get started with this language.

The first thing we are going to do is to write our shaders. As we laid out, we are going to do two things:

- Assign hardcoded vertex positions in a vertex shader

- Assign a hardcoded red color to every covered pixel in a fragment shader.

For these we will create a vertex shader and a fragment shader. In this tutorial shaders are going to be

a separate codebase from the rust codebase and they will not be placed in our rust crates. Instead we will

place them into a separate directory, shader_src, compile them separately into shader binaries

and load them during runtime. Within shader_src we will put our vertex and fragment shaders

into separate directories, shader_src/vertex_shaders and shader_src/fragment_shaders.

Our project directory will look like this:

┣━ Cargo.toml

┣━ build_tools

┣━ shader_src

┃ ┣━ vertex_shaders

┃ ┗━ fragment_shaders

┣━ vk_bindings

┃ ┣━ Cargo.toml

┃ ┣━ build.rs

┃ ┗━ src

┃ ┗━ lib.rs

┗━ vk_tutorial

┣━ Cargo.toml

┗━ src

┗━ main.rs

Vertex shader

Let's create a new file, I will call it 00_hardcoded_triangle.vert, and place it into the

shader_src/vertex_shaders directory.

We want to create a hardcoded array of vertex coordinates, load the coordinates of the vertex

processed by the current vertex shader instance and write it into the shader output. First I write down the

shader and then I will break down both what it does and the GLSL language features used.

#version 460

vec2 positions[3] = vec2[](

vec2(-0.5, -0.5),

vec2(-0.5, 0.5),

vec2( 0.5, 0.5)

);

void main()

{

vec2 position = positions[gl_VertexIndex];

gl_Position = vec4(position, 0.0, 1.0);

}

First we define the GLSL version of our source file.

Then we define a 3 element sized global array of constants, positions, and fill it with 3

two-dimensional vectors that contain the future coordinates of our vertices.

Then comes our main function, where we...

-

Use a built in variable,

gl_VertexIndexto index into thepositionsarray, reading one of its elements. - Extend it to be a 4 coordinate vector that has a third component of 0.0 and a fourth component of 1.0. Why a 4 component vector? That's an advanced topic that we will cover in our future 3D tutorial.

-

Assign it to a built in variable,

gl_Position. The vector written into this variable will be passed to the rasterizer for later use, when the pixels covered by the primitive using this vertex are determined.

What will the triangle look like? Coordinates can only be interpreted in a coordinate system, so let's talk about the ones we use. The window has a corner, a width and a height. You can create a 2D coordinate system inside it.

The framebuffer coordinates is a coordinate system where the origin is in the top left corner, and the image's boundaries are "width" and "height" units along the X and Y axes, the bottom right corner being in the [width, height] point. Adjacent pixels of the image are 1 unit apart from each other.

However vertex shaders need to scale to any image size, so Vertex shader outputs are interpreted in normalized device coordinates. Normalized device coordinates is the coordinate system where the top left corner is in the [-1, -1] position, the bottom right corner is in the [1, 1] position, and the center is in the origin.

The output of the vertex shader will be transformed to framebuffer coordinates. Our triangle is defined in normalized device coordinates and it looks like this:

Now that we have a vertex shader that creates triangle vertices, let's write our fragment shader!

Fragment shader

Now it's time to create our fragment shader, I will call it 00_hardcoded_red.frag, and place it

into the shader_src/fragment_shaders directory. In this shader we want to write a red color into

the pixel processed by the current fragment shader instance. Again, first I'm showing you the shader code,

then I break it down.

#version 460

layout(location = 0) out vec4 fragment_color;

void main()

{

fragment_color = vec4(1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0);

}

First we define the GLSL version of our source file, just like in the vertex shader.

Then, we define a so called out variable, the fragment_color. Writing into this variable will output

color into one of the color attachments of the currently used framebuffer. The layout(location = 0)

part determines which color attachment we write to. Specifically it identifies the color attachment with the index

of the attachment reference of the subpass. (At least when we use Render Passes in Vulkan.)

Then comes a main function just like in the vertex shader, but this time it's simpler. We simply

write a vec4 into fragment_color. The numbers in the constructor of

vec4 are the color components in this order: red = 1.0, green = 0.0, blue = 0.0 and alpha = 1.0.

The way we represent color components in GLSL looks like this: 1.0 is the maximum value of the color and 0.0

is the minimum value.

We finally have a vertex and a fragment shader in text format, but Vulkan consumes SPIR-V binaries. The next step is to compile them into SPIR-V.

Shader compilation

Our GLSL code needs to be compiled to SPIR-V, and this can be done with a compiler. We are going to use glslang, Khronos Group's reference frontend to GLSL. This one can output SPIR-V.

In this tutorial we are going to clone it, compile it from source and install it in our build_tools

directory.

git clone https://github.com/KhronosGroup/glslang

Now it's time to build it. At the time of writing the commands below successfully build glslang, but if anything goes wrong, the build instructions in the readme file of the glslang repo always contain the up to date build instructions.

The commands below require python. For Windows installing from the Windows store worked for me. For Linux you can install it from the repositories. For Arch Linux, the instructions can be found on the wiki.

Like in the devenv tutorial, feel free to replace

$install_dir with your choice. My $install_dir will be the build_tools

directory created in the

development environment tutorial.

cd glslang && \

./update_glslang_sources.py && \

mkdir build && \

cmake -B ./build -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release -DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=$install_dir && \

cd build && \

cmake --build . --config Release --target install

Now we can compile our shaders with the newly downloaded and built glslangValidator binary.

I'm adding a new directory for the shader binaries. This will be shaders in the project directory.

┣━ Cargo.toml

┣━ build_tools

┣━ shader_src

┃ ┣━ vertex_shaders

┃ ┗━ fragment_shaders

┣━ shaders

┣━ vk_bindings

┃ ┣━ Cargo.toml

┃ ┣━ build.rs

┃ ┗━ src

┃ ┗━ lib.rs

┗━ vk_tutorial

┣━ Cargo.toml

┗━ src

┗━ main.rs

Open a terminal and type the following! (If your directory structure differs, feel free to make the adjustments!)

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/00_hardcoded_triangle.vert.spv ./shader_src/vertex_shaders/00_hardcoded_triangle.vert

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/00_hardcoded_red.frag.spv ./shader_src/fragment_shaders/00_hardcoded_red.frag

Let's break down the first line, which compiles the vertex shader. The first part of the command is the path to the binary itself. Then

come three parameters. The -V flag tells the glslangValidator to emit SPIR-V, the

-o <filename> parameter specifies the output path of the output path, and the last one is the

path to the source file.

Pipeline creation

In the beginning of this chapter we described the graphics pipeline and its steps of rendering primitives to the image.

Some of these steps are programmable and require GPU programs to define their behavior. Some are fixed function, and only take a few parameters to customize what they do. In any case, GPU programs and additional configuration data need to be supplied to the GPU. In Vulkan, a pipeline is a Vulkan object that contains all the GPU programs and configuration data that's needed to prepare the GPU for work.

A special type of Vulkan pipeline called graphics pipeline can contain the configuration for input assembly, vertex shading, rasterization, fragment shading and color blending. (There may be more, but we will not go into that.) They are always paired up with a subpass of a render pass, and are configured to draw to the supbass' attachments.

In the following steps we will load our SPIR-V shaders, assemble the data for graphics pipeline creation, and create a graphics pipeline.

Shaders

First let's load our vertex shader. We need the Read trait from the std lib.

use vk_bindings::*;

use std::io::Read;

Then we need to load the shader binary into memory.

//

// Shader modules

//

// Vertex shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/00_hardcoded_triangle.vert.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

let mut bytecode = Vec::new();

file.read_to_end(&mut bytecode).expect("Failed to read vertex shader source");

Then we need to create a shader module.

In Vulkan a shader module is a vulkan object that represents shaders. They can be created from SPIR-V binaries.

This is how you create a shader module from SPIR-V binary:

//

// Shader modules

//

// Vertex shader

//...

let shader_module_create_info = VkShaderModuleCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_SHADER_MODULE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

codeSize: bytecode.len(),

pCode: bytecode.as_ptr() as *const u32

};

println!("Creating vertex shader module.");

let mut vertex_shader_module = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateShaderModule(

device,

&shader_module_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut vertex_shader_module

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create vertex shader. Error: {}", result);

}

...and add cleanup to the end of the program.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting vertex shader module");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyShaderModule(

device,

vertex_shader_module,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

The same goes for the fragment shader. Load from file, create shader module...

//

// Shader modules

//

// ...

// Fragment shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/00_hardcoded_red.frag.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

let mut bytecode = Vec::new();

file.read_to_end(&mut bytecode).expect("Failed to read fragment shader source");

let shader_module_create_info = VkShaderModuleCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_SHADER_MODULE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

codeSize: bytecode.len(),

pCode: bytecode.as_ptr() as *const u32

};

println!("Creating fragment shader module.");

let mut fragment_shader_module = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateShaderModule(

device,

&shader_module_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut fragment_shader_module

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create fragment shader. Error: {}", result);

}

...destroy shader module at the end.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe { vkDeviceWaitIdle(device) };

// ...

println!("Deleting fragment shader module");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyShaderModule(

device,

fragment_shader_module,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

Pipeline layout

The next thing we need for a pipeline state is a pipeline layout. The pipeline layout schematically lays out what kind of GPU resources (linear buffers and textures) and push constants will the pipeline use. Since right now we do not use any, our pipeline layout will be empty. The details of a pipeline layout will be covered in later chapters when we actually use it. Mostly in the uniform buffer chapter and in the texturing chapter.

//

// Pipeline layout

//

let pipeline_layout_create_info = VkPipelineLayoutCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_LAYOUT_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

setLayoutCount: 0,

pSetLayouts: core::ptr::null(),

pushConstantRangeCount: 0,

pPushConstantRanges: core::ptr::null()

};

println!("Creating pipeline layout.");

let mut pipeline_layout = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreatePipelineLayout(

device,

&pipeline_layout_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut pipeline_layout

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create pipeline layout. Error: {}", result);

}

Let's clean up at the end!

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting pipeline layout");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyPipelineLayout(

device,

pipeline_layout,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

Pipeline creation

Now it's time to get started with creating our Vulkan pipeline.

Shader stages

First we need to supply our shader modules for the list of programmable stages that we intend to use. In our case this is the vertex shader and the fragment shader.

//

// Pipeline state

//

let shader_stage_info = [

VkPipelineShaderStageCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_SHADER_STAGE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

pSpecializationInfo: core::ptr::null(),

stage: VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT,

module: vertex_shader_module,

pName: b"main\0".as_ptr() as *const i8

},

VkPipelineShaderStageCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_SHADER_STAGE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

pSpecializationInfo: core::ptr::null(),

stage: VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT,

module: fragment_shader_module,

pName: b"main\0".as_ptr() as *const i8

}

];

The fields that are important to us are stage, module and pName.

The stage field will be VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT for the vertex and

VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT for the fragment shader, the module will contain

the vertex and fragment shader's module, and pName is the entry point of the shader code.

In GLSL this will be the function called main. Since Vulkan is a C API, it receives this function name

b"main\0" as a null terminated C string.

We won't go into the remaining fields, but you can study the spec if you are curious.

Vertex input state

The vertex input state describes how vertices are loaded from memory. Since we hardcoded the vertices in the shader, we leave it empty. This will be covered in the next tutorial.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let vertex_input_state = VkPipelineVertexInputStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_VERTEX_INPUT_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

vertexBindingDescriptionCount: 0,

pVertexBindingDescriptions: core::ptr::null(),

vertexAttributeDescriptionCount: 0,

pVertexAttributeDescriptions: core::ptr::null()

};

Input assembly state

The input assembly defines the type of primitives we want to draw and how to interpret the list of indices defining each primitive. Here we fill this structure with the most basic information: we want to draw triangles, so the primitive topology will be triangle list, and we will disable primitive restart.

The triangle list topology means that the input assembly will supply a series of triangles. Since we are drawing a single triangle this is not very apparent, but in the next tutorial we will start drawing more than one triangle, and everything will make sense.

I will not go into details about primitive restart, because it's not very useful for triangle lists, and it's more of a niche feature. Some GPU optimization guides recommend using it, but for now it's out of scope.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let input_assembly_state = VkPipelineInputAssemblyStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_INPUT_ASSEMBLY_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

topology: VK_PRIMITIVE_TOPOLOGY_TRIANGLE_LIST,

primitiveRestartEnable: VK_FALSE

};

There. The field topology became VK_PRIMITIVE_TOPOLOGY_TRIANGLE_LIST, and

primitiveRestartEnable is VK_FALSE.

Viewport state

The viewport state contains the viewport and the scissor rectangle.

The vertices produced by the vertex shader are represented in normalized device coordinates. When we wrote the vertex shader, we already touched on the fact that these vectors need to be transformed into the attachments.

The viewport transformation is the transformation that will transform our coordinates from normalized device coordinates to framebuffer coordinates.

Beyond transforming the vertex we may also only want to render to a smaller portion of the screen.

The scissor rectangle defines a rectangle in framebuffer coordinates. Pixels covered by the rasterized primitive that fall outside the scissor rectangle will be discarded.

So the viewport transformation defines the transformation from normalized device coordinates to framebuffer coordinates, and the scissor determines which part of the framebuffer we are allowed to render to. Let's fill all the data Vulkan needs to define these!

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let (initial_width, initial_height) = (width, height);

let viewports = [

VkViewport {

x: 0.0,

y: 0.0,

width: initial_width as f32,

height: initial_height as f32,

minDepth: 0.0,

maxDepth: 1.0

}

];

let scissors = [

VkRect2D {

offset: VkOffset2D {

x: 0,

y: 0

},

extent: VkExtent2D {

width: initial_width,

height: initial_height

}

}

];

let viewport_state = VkPipelineViewportStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_VIEWPORT_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

viewportCount: viewports.len() as u32,

pViewports: viewports.as_ptr(),

scissorCount: scissors.len() as u32,

pScissors: scissors.as_ptr()

};

The struct VkViewport has x, y, width and height

fields identifying the portion of the framebuffer we want to transform our vertices to. We want to utilize the

whole image, so we set it to the whole image. What is minDepth and maxDepth? We will

only talk about that in one of the 3D chapters. For now let's just

assign these values.

The scissor rectangle is a VkRect2D struct with similar fields. Since we want to render to the

whole image, we don't want to reject anything and set this rectangle to cover the whole image as well.

Rasterization state

The rasterization state defines how the rasterizer will behave. It has various configurable functionalities, such as...

-

filling triangles or only drawing their borders with lines. The latter may be useful for debugging purposes

or in editors. This is controlled by the

polygonModevariable. -

discarding triangles that are backfacing. This is controlled by the

cullModeandfrontFacevariables. - ...and many more...

We do not need any of these for the sake of drawing a triangle to the screen, so we fill this structure in a quite simple way: let's fill the triangles we draw and disable every other fancy feature!

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let rasterization_state = VkPipelineRasterizationStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_RASTERIZATION_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

depthClampEnable: VK_FALSE,

rasterizerDiscardEnable: VK_FALSE,

polygonMode: VK_POLYGON_MODE_FILL,

cullMode: VK_CULL_MODE_NONE as VkCullModeFlags,

frontFace: VK_FRONT_FACE_COUNTER_CLOCKWISE,

depthBiasEnable: VK_FALSE,

depthBiasConstantFactor: 0.0,

depthBiasClamp: 0.0,

depthBiasSlopeFactor: 0.0,

lineWidth: 1.0

};

The field polygonMode will be VK_POLYGON_MODE_FILL, cullMode will be

VK_CULL_MODE_NONE, frontFace will be VK_FRONT_FACE_COUNTER_CLOCKWISE

lineWidth needs to be 1.0, and let's disable/zero out everything else.

Multisample state

Multisampling is an anti aliasing technique that sort of allows rendering with a higher resolution around the edges of a primitive, and mixing the results together. Since this is a tutorial about Vulkan basics, we do not enable it. Once you get comfortable with Vulkan, you may want to experiment with multisampling. For the API usage, Alexander Overvoorde has a Multisampling tutorial.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let multisample_state = VkPipelineMultisampleStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_MULTISAMPLE_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

rasterizationSamples: VK_SAMPLE_COUNT_1_BIT,

sampleShadingEnable: VK_FALSE,

minSampleShading: 1.0,

pSampleMask: core::ptr::null(),

alphaToCoverageEnable: VK_FALSE,

alphaToOneEnable: VK_FALSE

};

We set sampleShadingEnable to VK_FALSE and rasterizationSamples

to VK_SAMPLE_COUNT_1_BIT.

Color blend state

Color blend state describes what color channels to write to the image and how to mix the results of the fragment shader with the previous contents of the image. For instance, you may draw opaque objects that cover everything previously drawn, or you may draw transparent objects that need to be alpha blended with the previous contents.

Currently we have one image, the swapchain image, to render to, we want to write every color channel, and we

don't want any kind of transparency, we just want to overwrite the covered pixels with the color of our triangles.

First we create a VkPipelineColorBlendAttachmentState for our single color attachment, disable

blending and allow writing every color channel.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let color_blend_attachment_state = VkPipelineColorBlendAttachmentState {

blendEnable: VK_FALSE,

srcColorBlendFactor: VK_BLEND_FACTOR_ZERO,

dstColorBlendFactor: VK_BLEND_FACTOR_ZERO,

colorBlendOp: VK_BLEND_OP_ADD,

srcAlphaBlendFactor: VK_BLEND_FACTOR_ZERO,

dstAlphaBlendFactor: VK_BLEND_FACTOR_ZERO,

alphaBlendOp: VK_BLEND_OP_ADD,

colorWriteMask: (VK_COLOR_COMPONENT_R_BIT |

VK_COLOR_COMPONENT_G_BIT |

VK_COLOR_COMPONENT_B_BIT |

VK_COLOR_COMPONENT_A_BIT) as VkColorComponentFlags

};

The important one for blending is blendEnable, which is VK_FALSE. The rest are just

there to zero out every field. Then comes allowing to write every color, which is set by

colorWriteMask. This is a bitfield, and we set the bit of every color component to one, allowing

every color write.

Then we create a VkPipelineColorBlendStateCreateInfo and reference our single color attachment.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let color_blend_state = VkPipelineColorBlendStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_COLOR_BLEND_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

logicOpEnable: VK_FALSE,

logicOp: VK_LOGIC_OP_CLEAR,

attachmentCount: 1,

pAttachments: &color_blend_attachment_state,

blendConstants: [0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]

};

Other than the attachment references, there are certain settings in this struct that we disable and won't go into.

Create

Now that we have all of our programmable and fixed function state set up, it's time to reference all of these settings in an enormous

VkGraphicsPipelineCreateInfo variable, and call vkCreateGraphicsPipelines like this:

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

// Creation

let pipeline_create_info = VkGraphicsPipelineCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_GRAPHICS_PIPELINE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

stageCount: shader_stage_info.len() as u32,

pStages: shader_stage_info.as_ptr(),

pVertexInputState: &vertex_input_state,

pInputAssemblyState: &input_assembly_state,

pTessellationState: core::ptr::null(),

pViewportState: &viewport_state,

pRasterizationState: &rasterization_state,

pMultisampleState: &multisample_state,

pDepthStencilState: core::ptr::null(),

pColorBlendState: &color_blend_state,

pDynamicState: core::ptr::null(),

layout: pipeline_layout,

renderPass: render_pass,

subpass: 0,

basePipelineHandle: core::ptr::null_mut(),

basePipelineIndex: -1

};

println!("Creating pipeline.");

let mut non_dyn_pipeline = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateGraphicsPipelines(

device,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

1,

&pipeline_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut non_dyn_pipeline

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create pipeline. Error: {}", result);

}

Beyond the previously set up pipeline states that are referenced in a self explanatory way, it requires the

render pass in renderPass, the index of the subpass where it will be used in subpass,

and the pipeline layout in layout.

It was already mentioned that graphics pipelines are always paired up with render passes and subpasses. This way you can identify the attachments you need to render to. During rendering you can only use a graphics pipeline in its render pass and subpass.

Finally we have a pipeline that we can use and clean up at the end of our program!

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting non dyn pipeline");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyPipeline(

device,

non_dyn_pipeline,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

However, I will still create a second one just to demonstrate a fun little feature called dynamic state.

Dynamic state

There are parts of the fixed function stages that you can specify from the command buffer, and does not need to be defined during pipeline creation. The pipeline's dynamic state is a list of features that will not be baked into the pipeline, but will be recorded into the command buffer instead.

Viewport and scissor are a few of these, so for the sake of demonstration we are going to create a second pipeline with these parameters added to the dynamic state.

First we create a list of dynamic states, the viewport and the scissor, in an array. Then we create a dynamic state create info that references this array.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

// Dynamic state

let dynamic_state_array = [VK_DYNAMIC_STATE_VIEWPORT, VK_DYNAMIC_STATE_SCISSOR];

let dynamic_state = VkPipelineDynamicStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_DYNAMIC_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

dynamicStateCount: dynamic_state_array.len() as u32,

pDynamicStates: dynamic_state_array.as_ptr(),

};

// Creation

// ...

The VkDynamicState enum contains the parts of the pipeline that may be dynamic. We created an

array of a few of these enum values, namely VK_DYNAMIC_STATE_VIEWPORT and

VK_DYNAMIC_STATE_SCISSOR, and referenced this array in the

VkPipelineDynamicStateCreateInfo struct's dynamicStateCount and

pDynamicStates fields.

We create a new viewport state info that does not supply a viewport and a scissor rect.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let dyn_viewport_state = VkPipelineViewportStateCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_PIPELINE_VIEWPORT_STATE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

viewportCount: 1,

pViewports: core::ptr::null(),

scissorCount: 1,

pScissors: core::ptr::null()

};

// Creation

// ...

The fields viewportCount and scissorCount still has to be 1,

regardless of the pViewports and pScissors fields being null pointers,

otherwise the Validation layers will cry.

Now we create a new pipeline create info, reference these new structs, and create a new pipeline.

You can create several pipelines with one create pipeline call, and give the driver hints that can accelerate

pipeline creation. You can do this by supplying an already created pipeline as a base pipeline, or by supplying

an index to a create info supplied to vkCreateGraphicsPipelines.

Read the spec for more info!

We are going to try this one out as well. We will replace our existing non_dynamic_pipeline creation

with bulk creating our non dynamic and dynamic pipelines.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

// Creation

let pipeline_create_info_array = [

VkGraphicsPipelineCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_GRAPHICS_PIPELINE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

stageCount: shader_stage_info.len() as u32,

pStages: shader_stage_info.as_ptr(),

pVertexInputState: &vertex_input_state,

pInputAssemblyState: &input_assembly_state,

pTessellationState: core::ptr::null(),

pViewportState: &viewport_state,

pRasterizationState: &rasterization_state,

pMultisampleState: &multisample_state,

pDepthStencilState: core::ptr::null(),

pColorBlendState: &color_blend_state,

pDynamicState: core::ptr::null(),

layout: pipeline_layout,

renderPass: render_pass,

subpass: 0,

basePipelineHandle: core::ptr::null_mut(),

basePipelineIndex: -1

},

VkGraphicsPipelineCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_GRAPHICS_PIPELINE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

stageCount: shader_stage_info.len() as u32,

pStages: shader_stage_info.as_ptr(),

pVertexInputState: &vertex_input_state,

pInputAssemblyState: &input_assembly_state,

pTessellationState: core::ptr::null(),

pViewportState: &dyn_viewport_state,

pRasterizationState: &rasterization_state,

pMultisampleState: &multisample_state,

pDepthStencilState: core::ptr::null(),

pColorBlendState: &color_blend_state,

pDynamicState: &dynamic_state,

layout: pipeline_layout,

renderPass: render_pass,

subpass: 0,

basePipelineHandle: core::ptr::null_mut(),

basePipelineIndex: -1

}

];

println!("Creating pipelines.");

let mut pipelines = [core::ptr::null_mut(); 2];

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateGraphicsPipelines(

device,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

pipeline_create_info_array.len() as u32,

pipeline_create_info_array.as_ptr(),

core::ptr::null_mut(),

pipelines.as_mut_ptr()

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create pipelines. Error: {}", result);

}

let non_dyn_pipeline = pipelines[0];

let dyn_pipeline = pipelines[1];

This time the results are written into an array. I place these array elements into separate variables after creation.

We need to clean up this pipeline as well.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting dyn pipeline");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyPipeline(

device,

dyn_pipeline,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

And now we have a second pipeline whose viewport and scissor can be set from the command buffers during rendering. There are many other parameters that can be added to the list of dynamic states, and you can explore them by yourself.

Since it's good for learning and giving ideas, we are going to use both of our pipelines during rendering, just for Vulkan feature demoing. Let's get to it!

Rendering

Now it's time to render our triangle. However, in order to demonstrate both the dynamic and non dynamic state pipeline usage, we add a little twist. It won't be complicated. Promise! We are already past the hard part.

We will use the non dynamic pipeline initially, which has the viewport baked in for the initial resolution. Once resized, it will use the pipeline with dynamic state, and sets the viewport and scissor from the command buffe.

This may seem pointless. After all, when was the last time you could resize a window randomly and accidentally hit the exact previous resolution? Very little. I still do this for the sake of Vulkan feature demoing. This way the sample application contains the dynamic and non dynamic state path, and bulk pipeline creation as well. Write your real world application more pragmatically!

Now it's time to start rendering our triangle. Let's go to the part where we cleared our screen!

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

// ...

Our actual logic will look like this: if the current width and height of the window matches the initial one, we use the pipeline without dynamic state. If not, we use the one with dynamic state. Again, this is absolutely pointless, but this sample is more of a Vulkan feature demo. You want to be more pragmatical in your real world application.

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

if width == initial_width && height == initial_height

{

// Non dynamic branch

}

else

{

// Dynamic branch

}

// ...

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

// ...

Once we begin the render pass and the screen is cleared we are in the zeroth subpass. There we are allowed to

use our newly created pipeline and render our triangle. The command that will set the pipeline to be used for

subsequent draw calls is the vkCmdBindPipeline.

if width == initial_width && height == initial_height

{

vkCmdBindPipeline(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

VK_PIPELINE_BIND_POINT_GRAPHICS,

non_dyn_pipeline

);

}

else

{

// ...

}

For the non dynamic case, we need to manually set the viewport and the scissor

if width == initial_width && height == initial_height

{

// ...

}

else

{

vkCmdBindPipeline(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

VK_PIPELINE_BIND_POINT_GRAPHICS,

dyn_pipeline

);

let viewports = [

VkViewport {

x: 0.0,

y: 0.0,

width: width as f32,

height: height as f32,

minDepth: 0.0,

maxDepth: 1.0

}

];

vkCmdSetViewport(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

0,

viewports.len() as u32,

viewports.as_ptr()

);

let scissors = [

VkRect2D {

offset: VkOffset2D {

x: 0,

y: 0

},

extent: VkExtent2D {

width: width,

height: height

}

}

];

vkCmdSetScissor(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

0,

scissors.len() as u32,

scissors.as_ptr()

);

}

Next we need to issue a draw call using the vkCmdDraw command.

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

// ...

vkCmdDraw(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

3,

1,

0,

0

);

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

There. We issued a draw call that is going to draw 3 vertices onto the screen. The vkCmdDraw

has the following parameters: commandBuffer, which will be the current frame's command buffer,

vertexCount, which determines how many vertices we want to draw, which will be 3 for

a triangle, instanceCount, which can be used to render the same model many times, but for us it

will be 1, and the other two, firstVertex and firstInstance, which we

will talk about later, and for now just set them to

0.

It will launch an invocation of the vertex shader on the GPU for every vertex to calculate the vertex position. These invocations will run in parallel. Then it will be rasterized, and for every covered pixel an invocation of the fragment shader will be launched to calculate the pixel's color. Fragment shader invocations also run in parallel.

Let's remember the vertex shader's gl_VertexIndex variable! With the vertexCount

parameter set to 3, there will be three vertices with the index 0, 1 and 2. These will be

assigned to gl_VertexIndex, the vertex shader will index into the hardcoded array and

read the coordinates.

Let's run our program and see the results!

Finally our application draws a triangle!

Recap: Render passes, framebuffers, pipelines and rendering

In the clearing the screen chapter we already had to touch on render passes, subpasses, attachments and framebuffers, but a lot of their features were not utilized.

In this chapter we had to expand on these concepts to create our first graphics pipeline and issue our first draw call, basically filling our subpass with useful work. These are all interrelated and covering them is spilled across these two chapters. Now it's time for a recap and putting everything together.

A render pass is a data structure that contains a list of images that are rendered to called attachments, a list of subpasses that are units of rendering work reading from and/or writing to a subset of these images and a list of dependencies between subpasses. This data structure gives the driver a schematic of how our rendering work is organized. Based on this information the driver can find opportunities to optimize. An illustration from the clearing the screen chapter can be seen below.

In this chapter we created a graphics pipeline. During rendering the GPU applies a multi step process to render primitives to an image. The graphics pipeline we created contains all of the shaders and all of the configuration for the fixed function processing steps that are needed to execute the said multi step process inside a subpass. Specifically it defines the following:

- The type and data source of the primitives that enter the process.

- The way vertices get transformed.

- How primitives get rasterized.

- The way the color of covered pixels is calculated.

- How newly rendered pixels will be combined with preexisting data.

This was all planning. For actual execution we need specific data and specific rendering commands.

Framebuffers paired up an array of specific images with a Render Pass' attachments.

For the GPU to execute rendering work we needed commands, so we created command pools and command buffers where rendering commands can be recorded. In every frame we select one of the command buffers and record our rendering work, which consists of the following:

- We start a render pass instance with a specific framebuffer and clear colors. This way we set up what images we render to and fill them with an initial color. This starts the zeroth subpass as well.

- We bind the pipeline we created. This applies the GPU configuration we previously laid out.

- We record the draw call which issues rendering work.

- We end the render pass instance.

Once the command buffer is recorded, we submit it for execution. When it completes, we know the triangle is rendered to the image.

This is the overview of everything we have learned about rendering so far.

Wrapping up

Now our application can draw a triangle. We learned what the graphics pipeline is, what its steps are,

we wrote a vertex and a fragment shader, loaded it into the program, listed all the configuration we

wanted for the graphics pipeline, combined it into a VkPipeline object, used it during

rendering and issued a draw command to draw a triangle.

In the next tutorial we will swap out the hardcoded triangle with one that we supply from memory.

The sample code for this tutorial can be found here.

The tutorial continues here.