Specular lighting

In the previous chapter we have laid down the foundations for physically based rendering. We defined the physical quantity that we need to measure, radiance, we have learned about the rendering equation, we implemented diffuse lighting and converted our per pixel radiance value to sRGB values to be correctly interpreted by the swapchain. This laid down the foundation.

In this tutorial we extend the application with specular lighting. We will learn about how physics handles perfectly smooth surfaces and based on that we create a new model that handles surfaces that are not perfectly smooth. This will lead us to the Fresnel equations and their Schlick approximation, the Cook-Torrance BRDF and the Trowbridge-Reitz distribution. Once the theoretical basis is laid down, we extend our material data and implement specular lighting.

This tutorial is math and physics heavy and assumes you already have some intuition for calculus. The recommendations from the previous tutorials for consuming math still apply: you can understand math in many ways, depending on your way of thinking and background:

- Read and understand the math first, then the code

- Understand the code first, and then interpret the math

Read whichever way is better for you. Be prepared that multiple rereads may be necessary.

This tutorial is in open beta. There may be bugs in the code and misinformation and inaccuracies in the text. If you find any, feel free to open a ticket on the repo of the code samples.

Specular lighting

Microfacet model

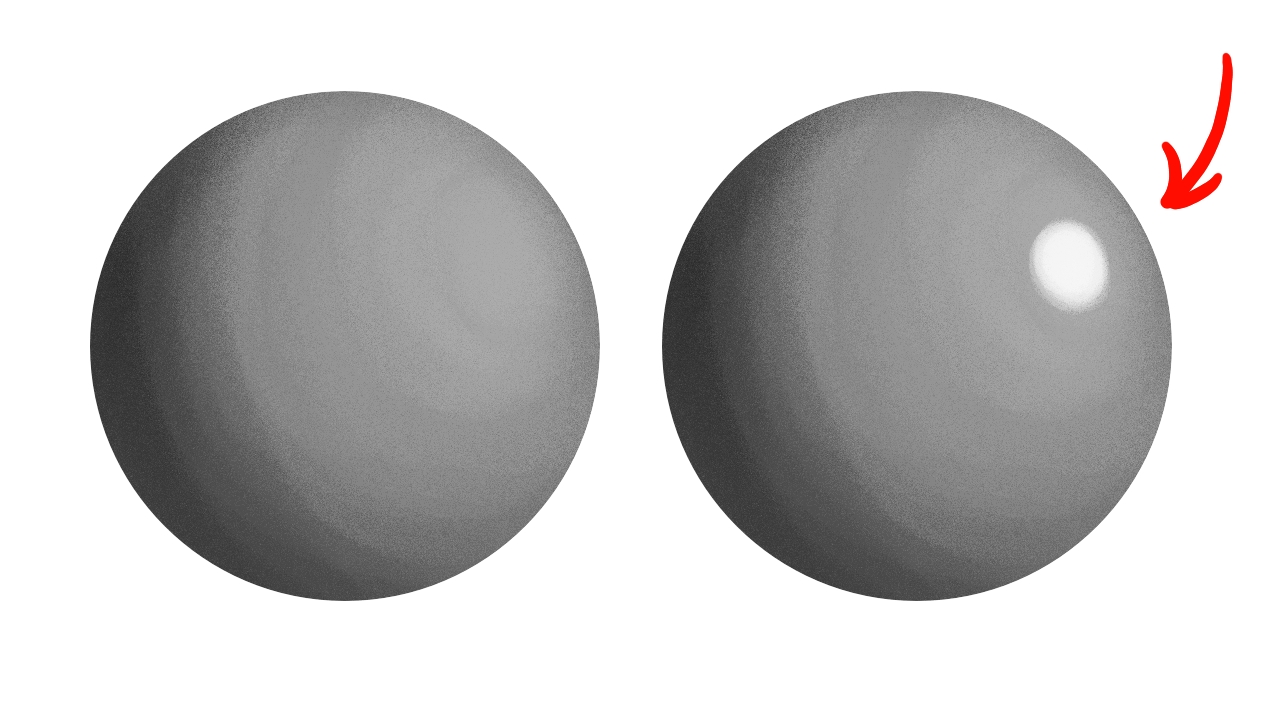

In the previous chapter we have implemented diffuse lighting, which gave us view independent lights and shadows. In the real world we almost always see view dependent bright highlights called specular highlights, and we can adjust our BRDF to yield these results in the fragment shader.

Let's remember that we want physically based rendering! We want to derive our equations from real world physics, so let's start with conceptualizing our problem, and then let's find some equations in physics that calculates what we need! In the real world solid objects and fluids are made our of some material, and "air" is made out of another material. Let's imagine light exiting our light sources and traveling in the "air". If we use electrodynamics as the foundation, the light is an electromagnetic wave, and its propagation is determined by the electromagnetic wave equation. The material properties (permeability and permittivity) of "air" influence the light's trajectory. If we assume that the electromagnetic field does not change the material properties, and the material properties are constant across space, our light should not change direction. When the light reaches the boundary of "air" and a solid object or a fluid, there is a sudden change in material properties. In this discontinuity point some light enters the material and some light gets reflected.

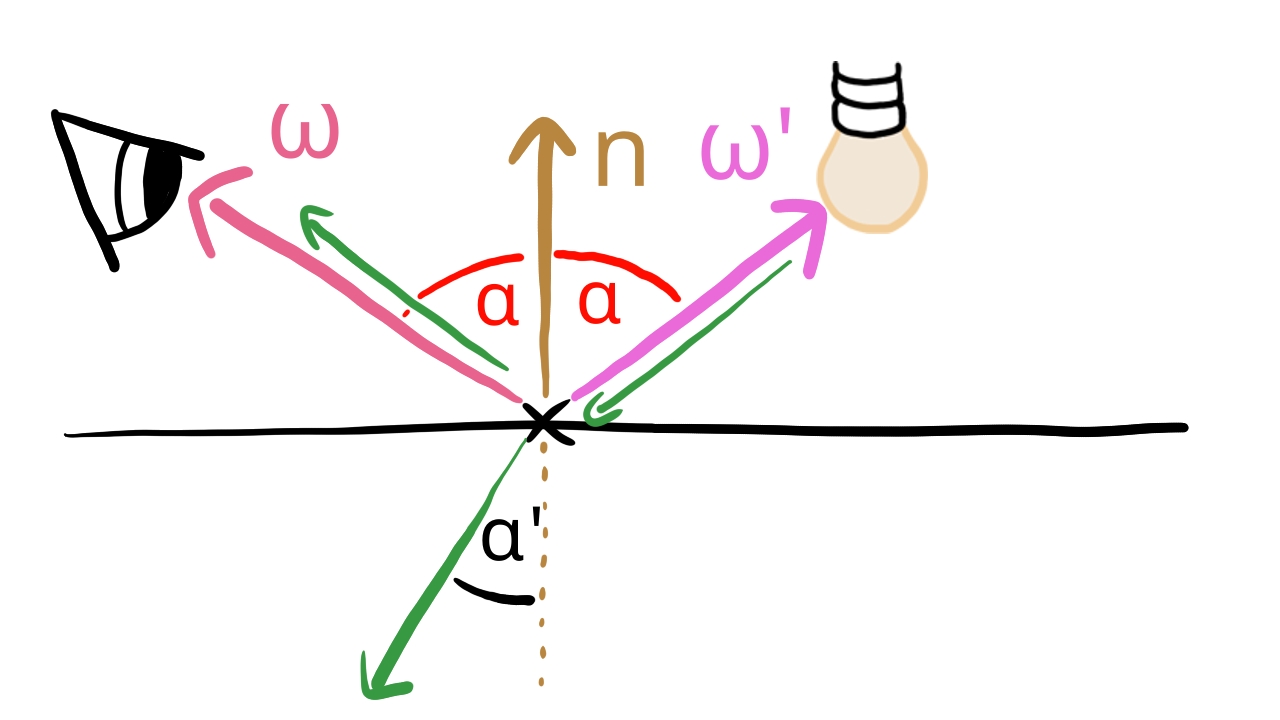

On a perfectly smooth surface the reflected light gets reflected into the mirror direction, and the amount of light that gets reflected is given by the Fresnel equations.

The Fresnel equations depend on the complex refractive index which consists of a real part, the refractive index and an imaginary part, the extinction coefficient. Instead of using the Fresnel equation itself, we use Schlick's approximation, which looks like this:

For calculating I chose the variant that can be found in the computer graphics lessons of László Szirmay-Kalos in this video. In this video is the real part of the complex refractive index and is the imaginary part, the extinction coefficient.

This equation uses a new value, to calculate the amount of light that gets reflected in the mirror direction, and we have an equation that lets us calculate this value from the complex refractive index of real world materials. The complex refractive index is wavelength dependent, and as a consequence, the is wavelength dependent as well, meaning that the amount of light reflected depends on the color of the light. Basically the value will determine the color of the surface. We can calculate from the complex refractive index if we want our material to have a golden, silver, copper, etc. color, we just have to look up the complex refractive index of the given material. A database can be found here. We can also set it to the desired color if we don't have a specific real life material in mind.

If we have a perfectly smooth surface, we would have a BRDF which only reflects into the mirror direction. The problem is, the chances of us looking from exactly the mirror direction is very close to zero, so we would almost never see a specular highlight. We also cannot represent surfaces that are not entirely smooth. The solution is the microfacet model.

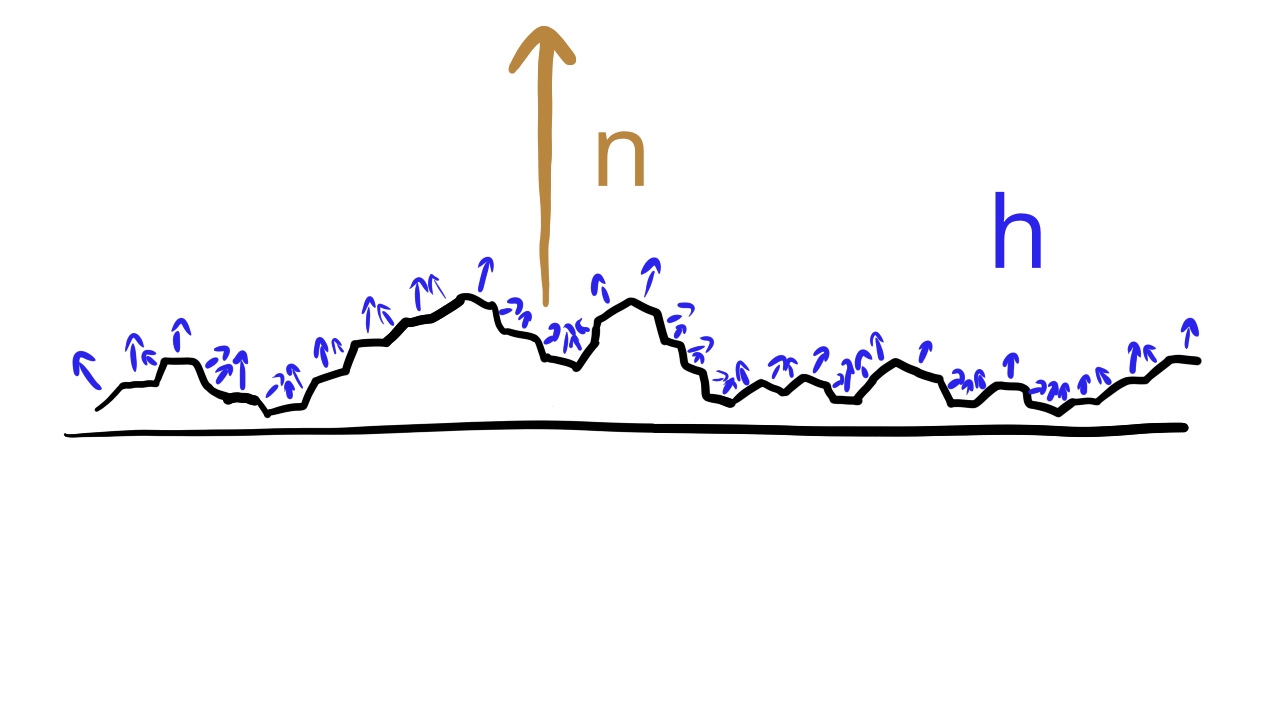

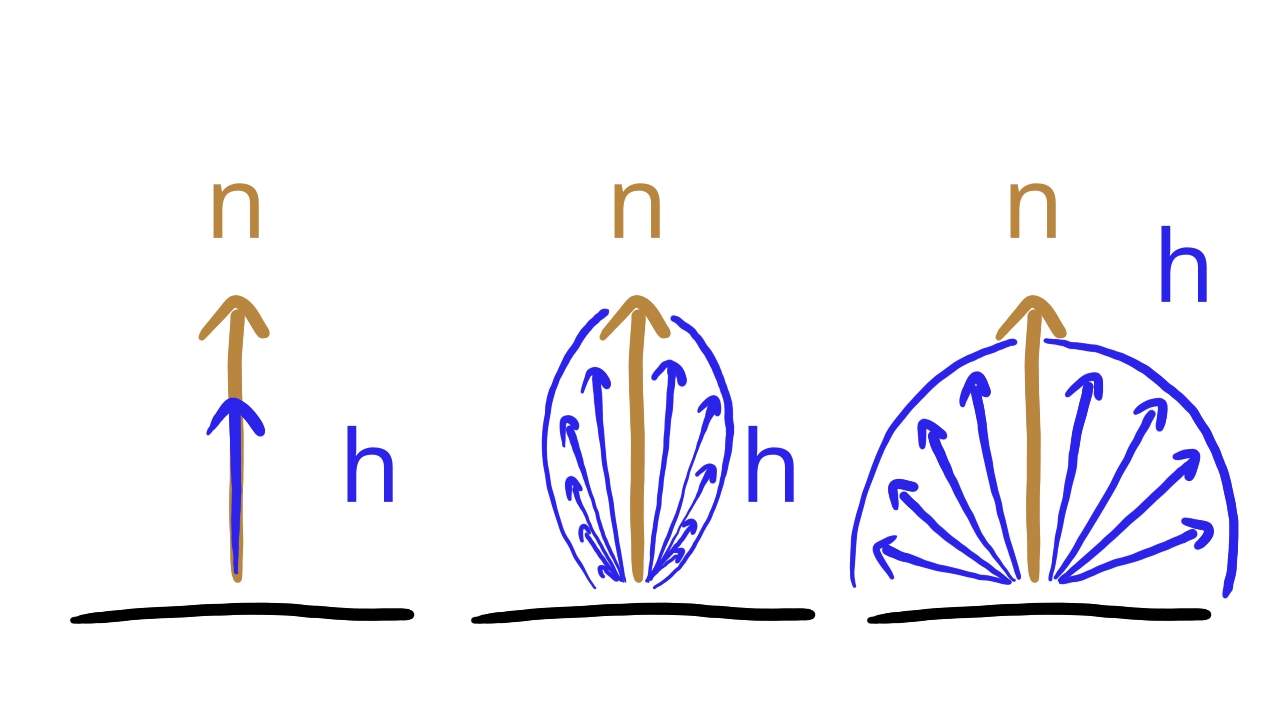

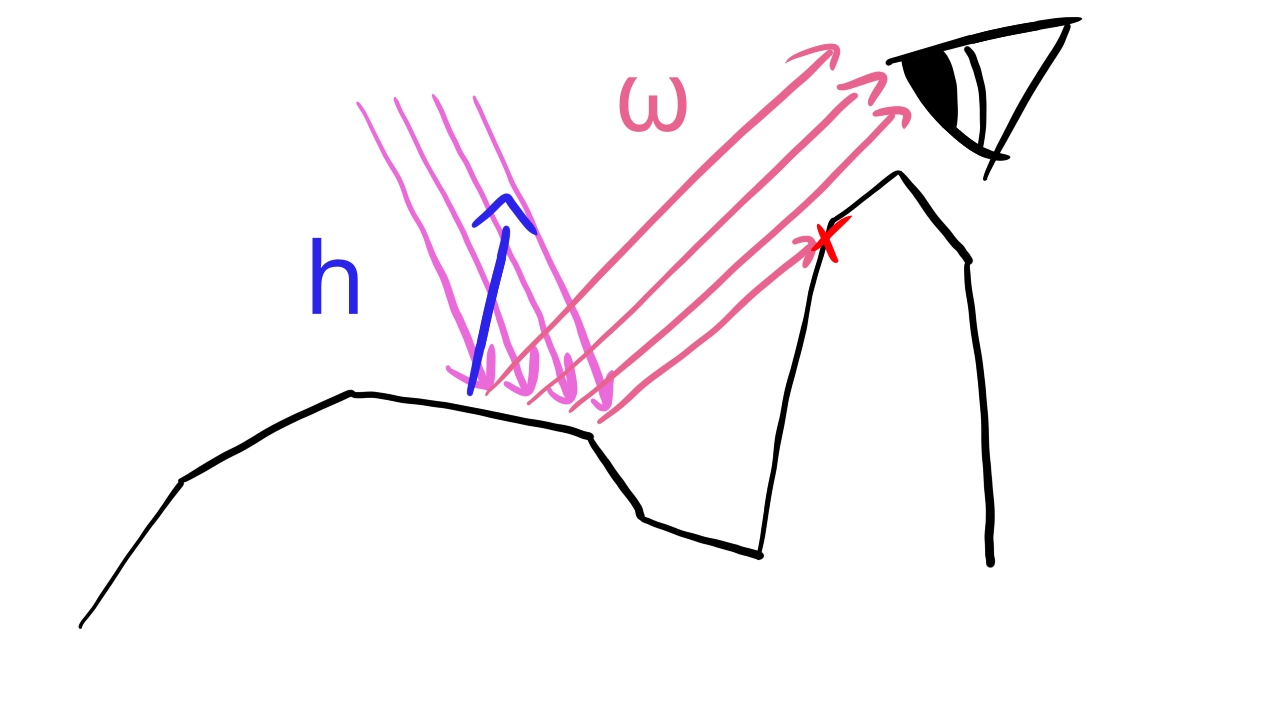

We assume that the surface area of a pixel consists of many small smooth surfaces. Some of the normals look in the direction of the surface normal , but some look in other directions. Then we take the light direction and the view direction, and we determine the half vector : the direction that is halfway between the two. If a perfectly smooth surface would reflect in the view direction, its normal would have to be the half vector. Then we take a distribution function, let it be which tells us what portion of the microfacets have the same normal as the half vector. We assume that this subset of the surfaces reflect light according to the Fresnel equation. We evaluate the Schlick approximation using the half vector as the normal vector, we evaluate the distribution function for the given half vector, and multiply them together. This will be the BRDF. So our BRDF is going to take the following form:

A BRDF of this form can finally give specular highlights in directions other than the exact mirror direction. We are done

with the physics background summary, we familiarized ourselves with the Fresnel equations and its Schlick approximation

and done some mathematical modeling to determine the guiding principles to build our specular BRDF what

remains is choosing the exact form of

Cook-Torrance BRDF

Now it's time to learn the industry standard BRDF for specular lighting. First our

Roughness is a variable that determines how spread out the microfacets' normal vectors are compared to the surface's normal. The value 0 will be perfectly smooth, which means that every microfacet's normal vector points in the direction of the surface normal, and 1 is the maximum roughness value. As the roughness increases, the more microfacets will diverge from the surface normal's direction while still clustering around the surface normal.

Now that we have a value between 0 and 1 to define the roughness of the material, let's introduce the BRDF that will take advantage of it, which will be the Cook-Torrance Microfacet Specular BRDF based on the Frostbite and the Unreal Engine 4 documents!

Let

Where

For calculating

Let's remember that if we have a refractive index and an extinction coefficient, we can calculate an

For

For the

Where

These are a lot of primitives that can all be assembled into the Cook-Torrance BRDF. If you have a light with a given

wavelength, the

Metals and non-metals

Let's take another step in the modeling process of incorporating the Cook-Torrance BRDF into our existing model! In PBR materials are commonly divided up into metals and non-metals.

Metals don't have a diffuse reflection, every reflected radiance comes from the specular component. For metals there is

an

Non-metals on the other hand have some diffuse reflection, that is what determines their color, and their specular

highlight "is not colored". We will have one

In order to determine whether the material is metal or non-metal, we need to introduce a new material property.

Metalness is a variable that determines whether the material will be shaded as a metal or as a non-metal.

The value 1 means that the material is shaded as a metal, with no diffuse lighting and a colored specular lighting

with a

Why should we transition smoothly for a metalness value between zero and one? Imagine that you have to draw a dirty metal object with your renderer! It makes sense that the parts where the metallic surface can be seen should be rendered in the metallic way, whereas the parts covered by mud should be rendered as non-metal. You can create a metalness texture, and have the value for metallic parts be 1, and the muddy parts be 0, but what will happen for the interpolated values on the boundary? You probably want a smooth transition.

We will discuss blending metal and non-metal reflected radiances when we discuss the fragment shader.

Blending Diffuse and Specular

Non-metals will need some diffuse lighting to give them color, and some specular lighting to give them the desired highlight. For this we need to combine their BRDFs. It cannot be done arbitrarily! We want physically based rendering and regardless of approximations and cheating we need to follow some rules.

A property of a BRDF is whether it is physically based. A physically based BRDF fulfills the following three criteria:

- It must be strictly positive for every input.

- It must be Helmholtz reciprocal.

- The integral of the function for the whole hemisphere should be less than one.

We are going to assume that the Cook-Torrance BRDF and the Lambertian diffuse BRDF separately fulfill the above criteria. Taking their weighted sum with weights adding up to one should yield a physically based BRDF. For this we will need an extra variable.

Reflectiveness determines the ratio of the diffuse and specluar lighting's contribution to the reflected radiance. A value of zero is perfectly diffuse, and a value of one is perfectly specular.

This is a variable that we can use to take the weighter sum of the two BRDFs. Let

Scene representation

The new BRDF requires new data, so let's talk about how to extend the scene representation to store the new data that we need.

The Cook-Torrance BRDF requires two new piece of data, an

Let's figure out what kind of material data structure we need to supply data into the equation! First let's remind ourselves of the different scenarios of metal and non-metal materials and what data they need!

-

Metals only have specular lighting and no diffuse lighting. They need an

F 0 F 0 -

Non-metals have some diffuse lighting and some specular lighting. The diffuse lighting determines its color,

and it needs its

ρ F 0 - In both scenarios we will need to store the metalness parameter as well to select which scheme to go with. This tutorial will feature smooth transition if the metalness is between 0 and 1, so we may need the data for both metals and non-metals.

Beyond that we have an existing emissive lighting which will stay the way it was.

We extend our material data the following way: the albedo will be a four element array. The first three elements will

be interpreted as either the

Then we add a float for the metalness parameter to determine whether we use the metal or non-metal version of the BRDF, a reflectiveness to blend the diffuse and specular BRDF together for non-metals, and the roughness for both the metal and non-metal specular BRDF.

Since the emissive lighting does not change, we will keep the array storing the emissive material parameter as it is.

So the new materials will need the albedo, the metalness, the reflectiveness, the roughness, and the emissive parameters. This is the data that we will need, so let's start coding it!

UBO layout

First we ajdust the GPU side scene representation. We have new material parameters, so we need to add them to the material data, and the specular BRDF is view dependent, so we need to upload the camera position to the fragment shader.

First let's add the material data. We need to add the roughness, metalness and reflectiveness. The existing albedo

will now contain the

struct MaterialData

{

vec4 albedo_fresnel;

vec4 roughness_mtl_refl;

vec4 emissive;

};

The first four floats will be the albedo_fresnel, which this time will contain the

The actual addition will be the second four floats, which will contain the roughness, the metalness and the reflectiveness. The fourth value will be the padding for the std140 memory layout.

The emissive is unchanged.

The matching rust struct will look like this:

//

// Uniform data

//

// ...

#[repr(C, align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct MaterialData

{

albedo: [f32; 4],

roughness: f32,

metalness: f32,

reflectiveness: f32,

std140_padding_0: f32,

emissive: [f32; 4]

}

// ...

Then we need to add the camera data. In this tutorial we pass the camera position in the same struct as the exposure value. This choice is arbitrary.

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 2) uniform UniformMaterialData {

float exposure_value;

vec3 camera_position;

MaterialData material_data[MAX_OBJECT_COUNT];

} uniform_material_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

The matching rust struct will look like this:

//

// Uniform data

//

// ...

#[repr(C, align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct ExposureAndCamData

{

exposure_value: f32,

std140_padding_0: f32,

std140_padding_1: f32,

std140_padding_2: f32,

camera_x: f32,

camera_y: f32,

camera_z: f32,

std140_padding_3: f32

}

// ...

Since we renamed a struct, let's update the place where we calculate our region size!

//

// Uniform data

//

// ...

// Per frame UBO material region size

let material_data_size = core::mem::size_of::<ExposureAndCamData>() + max_object_count * core::mem::size_of::<MaterialData>();

// ...

CPU side layout

In the CPU side scene representation we are adding the non-metal

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

struct StaticMesh

{

x: f32,

y: f32,

z: f32,

scale: f32,

rot_x: f32,

rot_y: f32,

albedo_r: f32,

albedo_g: f32,

albedo_b: f32,

fresnel: f32,

roughness: f32,

metalness: f32,

reflectiveness: f32,

emissive_r: f32,

emissive_g: f32,

emissive_b: f32,

texture_index: u32,

model_index: usize

}

// ...

Now we fill the example scene with new data.

I just create a single non-metal fresnel, and set every scene object's fresnel to it. You can do something else.

//

// Model and Texture ID-s

//

// ...

// Materials

let non_metal_fresnel = 0.5;

Like in the previous tutorials, instead of only inlining the value of the new fields, I inline the whole scene. This will get long...

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

let mut static_meshes = Vec::with_capacity(max_object_count);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 0.25,

y: 0.0,

z: -1.25,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: triangle_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 0.25,

y: -0.25,

z: -2.0,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 0.75,

albedo_g: 0.5,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: triangle_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -0.25,

y: 0.25,

z: -3.0,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 0.75,

albedo_g: 0.5,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: quad_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 1.5,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.6,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: quad_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -1.5,

y: 0.0,

z: -2.6,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: quad_index

}

);

// Cubes added later

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 1.0,

y: 0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 1.0,

y: -0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -1.0,

y: 0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -1.0,

y: -0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: cube_index

}

);

// Spheres added later

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 2.0,

y: 0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: sphere_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 2.0,

y: -0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: sphere_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -2.0,

y: 0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: sphere_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: -2.0,

y: -0.5,

z: -2.5,

scale: 0.25,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: 0.1,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.25,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: sphere_index

}

);

// ...

This is my example scene that I use in the samples.

Data upload

Now we need to update the part where we copy data from the CPU side to the current frame's uniform buffer region.

//

// Uniform upload

//

{

// Getting references

// ...

let current_frame_material_region_offset = (

total_transform_data_size +

current_frame_index * padded_material_data_size

) as isize;

let exposure_data;

let material_data_array;

unsafe

{

let per_frame_material_region_begin = uniform_buffer_ptr.offset(

current_frame_material_region_offset

);

let exposure_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<ExposureAndCamData> = core::mem::transmute(

per_frame_material_region_begin

);

exposure_data = &mut *exposure_data_ptr;

let material_offset = core::mem::size_of::<ExposureAndCamData>() as isize;

let material_data_ptr: *mut core::mem::MaybeUninit<MaterialData> = core::mem::transmute(

per_frame_material_region_begin.offset(material_offset)

);

material_data_array = core::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(

material_data_ptr,

max_object_count

);

}

// ...

// Filling them with data

// ...

*exposure_data = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

ExposureAndCamData {

exposure_value: exposure_value,

std140_padding_0: 0.0,

std140_padding_1: 0.0,

std140_padding_2: 0.0,

camera_x: camera.x,

camera_y: camera.y,

camera_z: camera.z,

std140_padding_3: 0.0

}

);

let static_mesh_material_data_array = &mut material_data_array[..static_meshes.len()];

for (i, static_mesh) in static_meshes.iter().enumerate()

{

static_mesh_material_data_array[i] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

MaterialData {

albedo: [

static_mesh.albedo_r,

static_mesh.albedo_g,

static_mesh.albedo_b,

static_mesh.fresnel

],

roughness: static_mesh.roughness,

metalness: static_mesh.metalness,

reflectiveness: static_mesh.reflectiveness,

std140_padding_0: 0.0,

emissive: [

static_mesh.emissive_r,

static_mesh.emissive_g,

static_mesh.emissive_b,

0.0

]

}

);

}

// ...

let light_material_data_array = &mut material_data_array[static_meshes.len()..static_meshes.len() + lights.len()];

for (i, light) in lights.iter().enumerate()

{

let mlt = 1.0 / (point_light_radius * point_light_radius);

light_material_data_array[i] = core::mem::MaybeUninit::new(

MaterialData {

albedo: [

0.0,

0.0,

0.0,

0.0

],

roughness: 0.0,

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.0,

std140_padding_0: 0.0,

emissive: [

light.intensity_r * mlt,

light.intensity_g * mlt,

light.intensity_b * mlt,

0.0

]

}

);

}

}

All that remains is making use of this data in the fragment shader.

Shader programming

Fragment shader

Now we adjust the material data structure in the fragment shader, and also add the camera position which the specular BRDF will need. Then we implement the metal and non-metal shading logic using the Cook-Torrance BRDF.

#version 460

const float PI = 3.14159265359;

const uint MAX_TEX_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 2;

const uint MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 8;

const uint MAX_OBJECT_COUNT = 64;

const uint MAX_LIGHT_COUNT = 64;

layout(set = 0, binding = 1) uniform sampler2D tex_sampler[MAX_TEX_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

const uint ROUGHNESS = 0;

const uint METALNESS = 1;

const uint REFLECTIVENESS = 2;

struct MaterialData

{

vec4 albedo_fresnel;

vec4 roughness_mtl_refl;

vec4 emissive;

};

struct LightData

{

vec4 position;

vec4 intensity;

};

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 2) uniform UniformMaterialData {

float exposure_value;

vec3 camera_position;

MaterialData material_data[MAX_OBJECT_COUNT];

} uniform_material_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 3) uniform UniformLightData {

uint light_count;

LightData light_data[MAX_LIGHT_COUNT];

} uniform_light_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

layout(push_constant) uniform ResourceIndices {

uint obj_index;

uint ubo_desc_index;

uint texture_id;

} resource_indices;

layout(location = 0) in vec3 frag_position;

layout(location = 1) in vec3 frag_normal;

layout(location = 2) in vec2 frag_tex_coord;

layout(location = 0) out vec4 fragment_color;

vec4 fresnel_schlick(vec4 fresnel, float camera_dot_half)

{

return fresnel + (1.0 - fresnel) * pow(max(0.0, 1.0 - camera_dot_half), 5);

}

float trowbridge_reitz_distribution(float alpha, float normal_dot_half)

{

float alpha_sqr = alpha * alpha;

float normal_dot_half_sqr = normal_dot_half * normal_dot_half;

float div_sqr_part = (normal_dot_half_sqr * (alpha_sqr - 1) + 1);

return alpha_sqr / (PI * div_sqr_part * div_sqr_part);

}

float smith_lambda(float roughness, float cos_angle)

{

float cos_sqr = cos_angle * cos_angle;

float tan_sqr = (1.0 - cos_sqr)/cos_sqr;

return (-1.0 + sqrt(1 + roughness * roughness * tan_sqr)) / 2.0;

}

void main()

{

uint texture_id = resource_indices.texture_id;

uint obj_index = resource_indices.obj_index;

uint ubo_desc_index = resource_indices.ubo_desc_index;

// Lighting

vec3 normal = frag_normal;

if (!gl_FrontFacing)

{

normal *= -1.0;

}

normal = normalize(normal);

vec3 camera_position = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].camera_position.xyz;

vec3 camera_direction = normalize(camera_position - frag_position);

float camera_dot_normal = dot(camera_direction, normal);

vec4 albedo_fresnel = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].material_data[obj_index].albedo_fresnel;

float roughness = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].material_data[obj_index].roughness_mtl_refl[ROUGHNESS];

float metalness = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].material_data[obj_index].roughness_mtl_refl[METALNESS];

float reflectiveness = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].material_data[obj_index].roughness_mtl_refl[REFLECTIVENESS];

vec4 tex_color = texture(tex_sampler[texture_id], frag_tex_coord);

vec3 diffuse_brdf = albedo_fresnel.rgb * tex_color.rgb / PI;

vec3 radiance = vec3(0.0);

for (int i=0;i < uniform_light_data[ubo_desc_index].light_count;i++)

{

vec3 light_position = uniform_light_data[ubo_desc_index].light_data[i].position.xyz;

vec3 light_intensity = uniform_light_data[ubo_desc_index].light_data[i].intensity.rgb;

vec3 light_direction = light_position - frag_position;

float light_dist_sqr = dot(light_direction, light_direction);

light_direction = normalize(light_direction);

// Diffuse

float light_dot_normal = dot(normal, light_direction);

vec3 diffuse_coefficient = diffuse_brdf * light_dot_normal;

// Specular

vec3 half_vector = normalize(light_direction + camera_direction);

float normal_dot_half = dot(normal, half_vector);

float camera_dot_half = dot(camera_direction, half_vector);

float light_dot_half = dot(light_direction, half_vector);

float alpha = roughness * roughness;

vec4 F = fresnel_schlick(albedo_fresnel, camera_dot_half);

float D = trowbridge_reitz_distribution(alpha, normal_dot_half);

float G = step(0.0, camera_dot_half) * step(0.0, light_dot_half) / (1.0 + smith_lambda(roughness, camera_dot_normal) + smith_lambda(roughness, light_dot_normal));

vec4 specular_brdf = F * D * G / (4.0 * max(1e-2, camera_dot_normal));

vec3 metallic_contrib = specular_brdf.rgb;

vec3 non_metallic_contrib = vec3(specular_brdf.a);

vec3 specular_coefficient = mix(non_metallic_contrib, metallic_contrib, metalness);

radiance += mix(diffuse_coefficient, specular_coefficient, reflectiveness) * step(0.0, light_dot_normal) * light_intensity / light_dist_sqr;

}

vec3 emissive = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].material_data[obj_index].emissive.rgb;

radiance += emissive;

// Exposure

float exposure_value = uniform_material_data[ubo_desc_index].exposure_value;

float ISO_speed = 100.0;

float lens_vignetting_attenuation = 0.65;

float max_luminance = (78.0 / (ISO_speed * lens_vignetting_attenuation)) * exp2(exposure_value);

float max_spectral_lum_efficacy = 683.0;

float max_radiance = max_luminance / max_spectral_lum_efficacy;

float exposure = 1.0 / max_radiance;

vec3 exp_radiance = radiance * exposure;

// Tone mapping

float a = 2.51f;

float b = 0.03f;

float c = 2.43f;

float d = 0.59f;

float e = 0.14f;

vec3 tonemapped_color = clamp((exp_radiance*(a*exp_radiance+b))/(exp_radiance*(c*exp_radiance+d)+e), 0.0, 1.0);

// Linear to sRGB

vec3 srgb_lo = 12.92 * tonemapped_color;

vec3 srgb_hi = 1.055 * pow(tonemapped_color, vec3(1.0/2.4)) - 0.055;

vec3 srgb_color = vec3(

tonemapped_color.r <= 0.0031308 ? srgb_lo.r : srgb_hi.r,

tonemapped_color.g <= 0.0031308 ? srgb_lo.g : srgb_hi.g,

tonemapped_color.b <= 0.0031308 ? srgb_lo.b : srgb_hi.b

);

fragment_color = vec4(srgb_color, 1.0);

}

We already discussed the addition of material and camera data at the uniform buffer layout section.

In the main function we calculate the camera direction and the dot product of the camera and the normal vector, and

create a few shortcuts for the material data. We read the albedo, the

albedo_fresnel in the fourth coordinate.

Then we calculate the diffuse

Then we get the light data and calculate the distance squared and the light direction as we did before. The first

interesting part happens after. We store the coefficient of the reflected diffuse lighting,

diffuse_brdf * light_dot_normal for later use. Notice how it's no longer

max(0.0, dot(normal, light_direction))! We will zero out the contribution of light sources behind the

face differently.

Then we start implementing the Cook-Torrance BRDF. First we calculate the half vector. Then the BRDF contains the dot product of many of the vectors. The Fresnel factor depends on the dot product of the camera direction and the half vector, the Trowbridge-Reitz NDF depends on the dot product of the normal vector and the half vector, so we calculate them all at the beginning.

We calculate the Fresnel factor F, implemented by the fresnel_schlick function. It is a direct

implementation of the Schlick approximation, except it takes a vec4. Basically it calculates the Fresnel factor for

the metal case and the non metal case in one go. Then we calculate the NDF value D for the given roughness

value, normal and half vector. Again the trowbridge_reitz_distribution is a direct implementation of the

equation from the beginning of the chapter. Afterwards we calculate the G geometric attenuation using the

Smith visibility function. Finally we put it all together into something that is almost the specular BRDF. We name this

specular_brdf but it differs just a bit: the dot product of the light direction and the normal is missing

from the divisor, because it cancels out with the same dot product in the dividend of the whole rendering equation.

Then we create the formula that combines the metal and non-metal case, and the diffuse and specular parts. This is where I made some decisions that you may not agree with, and you may want to implement things differently. As we said in the intro, the metal case has no diffuse. To get this result with my implementation, the reflectiveness must be zero. The way I implemented it in this tutorial first we linearly interpolate the metal and non-metal specular, and then we linearly interpolate the diffuse and specular coefficients. If the metal and the reflectiveness are both nonzero, the metallic object will have a diffuse light, which is wrong. You may not agree with this implementation and in that case feel free to adjust it!

Finally we take this summed up coefficient and multiply the point light radiant intensity and the inverse square falloff.

I want to call your attention to the extra multiplication with the step(0.0, light_dot_normal). Since

this dot product gets eliminated in the specular lighting, I just use this factor to zero out the specular contribution

(and the diffuse as well) if the light is behind the surface.

I saved this file as 03_specular_lighting.frag.

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/03_specular_lighting.frag.spv ./shader_src/fragment_shaders/03_specular_lighting.frag

Once our binary is ready, we need to load.

//

// Shader modules

//

// ...

// Fragment shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/03_specular_lighting.frag.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

// ...

...and that's it!

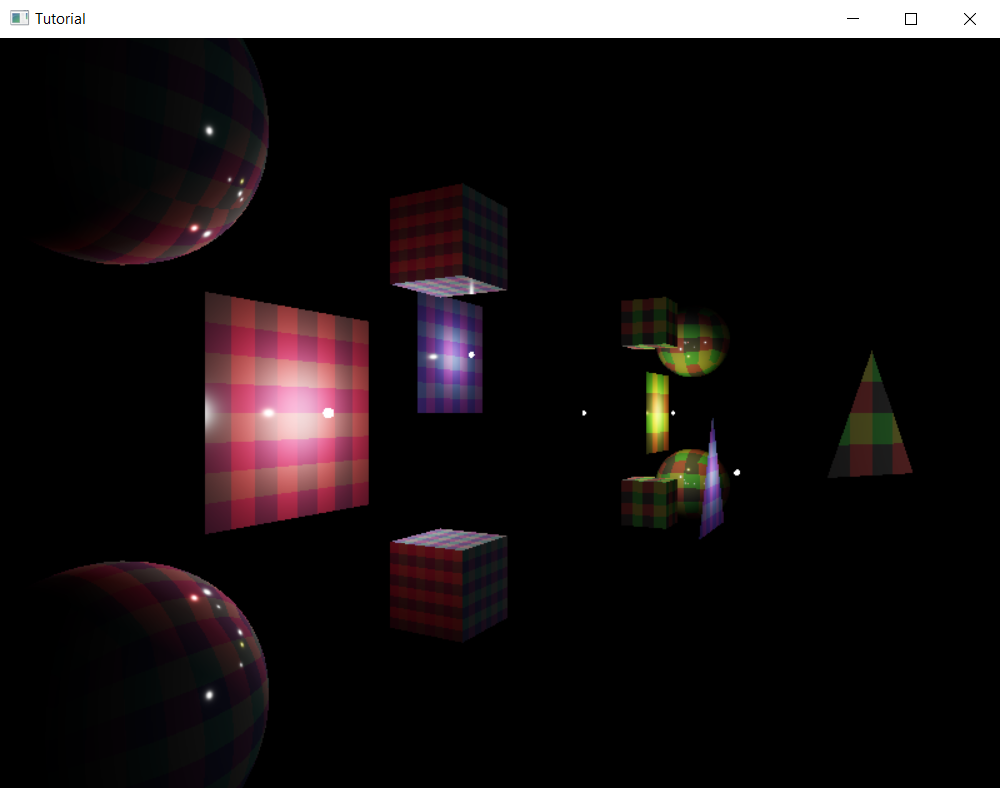

Now if we move around, scene objects will show a view dependent specular highlight.

It's cute, but there is a problem: we do not have metallis objects in the scene! We also do not have objects with differing roughness in the scene! We must remedy this, because we need test data where we can see the results!

Bonus: Adding balls with different materials and roughness

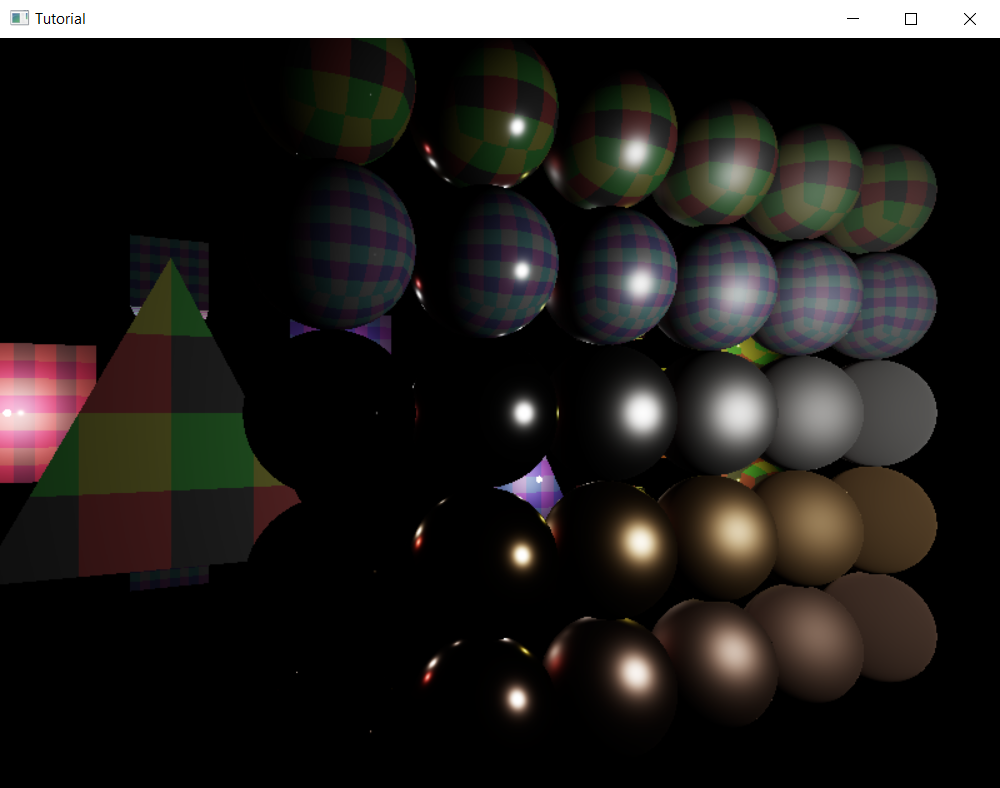

Adding spheres with different materials and different roughness is a common way to visualize the results of PBR. We are going to arrange them in a grid, each row corresponding to a material, and each column corresponding to a roughness value. Let's get started!

The metallic spheres will be of three materials: gold, silver and copper. We need to get material data for them somehow.

Generally materials are described with their refractive index and their extinction coefficient, but let's remember that

we represent them with their

fn calculate_fresnel(refractive_index: f32, extinction_coefficient: f32) -> f32

{

((refractive_index - 1.0).powi(2) + extinction_coefficient.powi(2)) /

((refractive_index + 1.0).powi(2) + extinction_coefficient.powi(2))

}

fn calculate_fresnel_rgb(refractive_index: [f32; 3], extinction_coefficient: [f32; 3]) -> [f32; 3]

{

[

calculate_fresnel(refractive_index[0],extinction_coefficient[0]),

calculate_fresnel(refractive_index[1],extinction_coefficient[1]),

calculate_fresnel(refractive_index[2],extinction_coefficient[2])

]

}

Now we can read the refractive index and the extinction coefficient for the red, green and blue wavelengths from any database. One of these databases can be found here. Let's calculate the albedos for these materials and store them!

//

// Model and Texture ID-s

//

// ...

// Materials

// ...

// Source: https://refractiveindex.info/?shelf=3d&book=metals&page=copper

// Gold

let gold_refractive_index = [0.18601, 0.59580, 1.4120];

let gold_extinction_coeff = [3.3762, 2.0765, 1.7827];

let gold_albedo = calculate_fresnel_rgb(gold_refractive_index, gold_extinction_coeff);

// Silver

let silver_refractive_index = [0.15865, 0.14215, 0.13533];

let silver_extinction_coeff = [3.8929, 3.0051, 2.3276];

let silver_albedo = calculate_fresnel_rgb(silver_refractive_index, silver_extinction_coeff);

// Copper

let copper_refractive_index = [0.28046, 0.85418, 1.3284];

let copper_extinction_coeff = [3.5587, 2.4518, 2.2949];

let copper_albedo = calculate_fresnel_rgb(copper_refractive_index, copper_extinction_coeff);

// ...

Now let's add balls that use these material properties in a for loop!

//

// Game state

//

// ...

// Game logic state

// ...

let min_roughness: f32 = 0.01;

let max_demo_spheres = 6;

for i in 0..max_demo_spheres

{

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 0.5 - i as f32 * 0.25,

y: 0.5,

z: -0.75,

scale: 0.125,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: min_roughness.max(1.0 - i as f32 * (1.0 / (max_demo_spheres - 1) as f32)),

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.75,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: red_yellow_green_black_tex_index,

model_index: sphere_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 0.5 - i as f32 * 0.25,

y: 0.25,

z: -0.75,

scale: 0.125,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: 1.0,

albedo_g: 1.0,

albedo_b: 1.0,

fresnel: non_metal_fresnel,

roughness: min_roughness.max(1.0 - i as f32 * (1.0 / (max_demo_spheres - 1) as f32)),

metalness: 0.0,

reflectiveness: 0.75,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: sphere_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 0.5 - i as f32 * 0.25,

y: 0.0,

z: -0.75,

scale: 0.125,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: silver_albedo[0],

albedo_g: silver_albedo[1],

albedo_b: silver_albedo[2],

fresnel: 0.0,

roughness: min_roughness.max(1.0 - i as f32 * (1.0 / (max_demo_spheres - 1) as f32)),

metalness: 1.0,

reflectiveness: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: sphere_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 0.5 - i as f32 * 0.25,

y: -0.25,

z: -0.75,

scale: 0.125,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: gold_albedo[0],

albedo_g: gold_albedo[1],

albedo_b: gold_albedo[2],

fresnel: 0.0,

roughness: min_roughness.max(1.0 - i as f32 * (1.0 / (max_demo_spheres - 1) as f32)),

metalness: 1.0,

reflectiveness: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: sphere_index

}

);

static_meshes.push(

StaticMesh {

x: 0.5 - i as f32 * 0.25,

y: -0.5,

z: -0.75,

scale: 0.125,

rot_x: 0.0,

rot_y: 0.0,

albedo_r: copper_albedo[0],

albedo_g: copper_albedo[1],

albedo_b: copper_albedo[2],

fresnel: 0.0,

roughness: min_roughness.max(1.0 - i as f32 * (1.0 / (max_demo_spheres - 1) as f32)),

metalness: 1.0,

reflectiveness: 1.0,

emissive_r: 0.0,

emissive_g: 0.0,

emissive_b: 0.0,

texture_index: blue_cyan_magenta_white_tex_index,

model_index: sphere_index

}

);

}

...and the result is the following:

Now this looks very underwhelming. Glossy metallic spheres are black instead of gold/silver/copper colored, except for the tiny specular highlight. In the previous chapter when we simplified the rendering equation we decided to only simulate direct lighting, and metallic objects look ugly without indirect illumination. This pretty much sets up where we need to go next, we need to implement some indirect illumination, but that is for later tutorials. We finally have specular lighting, so let's conclude this one here!

Wrapping up

In this chapter we extended our application with specular lighting, which added a view dependent highlight to our scene elements. Doing this in the physically based way required us to collect information from two of the most important pieces of literature, the Frostbite doc and the Unreal engine doc, and learn about the Cook-Torrance BRDF.

Then we implemented it, and added some test data, and we have the highlight we needed, but we also discovered that physically based rendering is ugly without indirect illumination.

In the next few chapters we will implement an indirect illumination technique called environment mapping. It is very commonly used in real time PBR. First we will learn about cubemaps, and then we will use them for global illumination.

The sample code for this tutorial can be found here.

The tutorial continues here.