Texture

In the previous chapter we extended our application to render a whole scene, but our scene elements still had a single color.

In this chapter we are going to learn texturing: how to add detail to our models by reading colors per pixel from an image.

This tutorial is in open beta. There may be bugs in the code and misinformation and inaccuracies in the text. If you find any, feel free to open a ticket on the repo of the code samples.

Textures and texture coordinates

Our fragment shader from the hardcoded triangle chapter assigned a red color to every pixel covered by a triangle. This was good enough for understanding basic concepts but in a real world application you want to add detail to your scene elements.

One of the extremely common ways of doing that is storing the details in an image, mapping a subset of the image to our triangles, after rasterization reading the image data corresponding to the pixel, and using it to calculate the pixel color. This mapping happens using texture coordinates. We define a 2D coordinate system for the image, assign 2D vectors in this space to every vertex and use these coordinates to figure our what data to read from the image.

Texture space is a 2D coordinate system where the origin is in one of the corners, and the axes go along the sides of the image.

Texture coordinates are 2D vectors in texture space.

Our models have vertices that defines their position. We can assign a texture coordinate to every vertex of our models. Then every triangle of our model will have a corresponding triangle defined in texture space. We can map the portion of the image covered by this texture space triangle to the corresponding model space triangle.

Ok, we can now get texture coordinates to the corners of the triangle, but there will be covered pixels in-between. How do we get texture coordinates for them, hopefully with a smooth transition between them? Once the triangle is rasterized using its normalized device coordinates, every covered pixel will have a position. This position can be expressed as the weighted sum of the ndc vertex coordinates. The weights will take a specific value. If we sum the uv coordinates of the corners with these same weights, we will get a texture coordinate for the pixel in-between, read the image at this coordinate, and be happy.

Now that we talked about basic concepts, let's talk about some conventions!

Texture coordinates tend to be named [u,v], u being the horizontal and v being the vertical coordinate.

In this tutorial we will use normalized texel coordinates, which means that the [0,0], [0,1], [1,0], [1,1] correspond to the corners of the image. I will name the [0,0] point to be the bottom left corner of the image, and the [1,1] point to be the top right.

Now that we have enough details to conceptualize how we are going to do things, let's talk about image sampling in shaders!

Sampler variables and attribute interpolation

First let's talk about images. The language construct for accessing images is similar to the ones accessing buffers: they are represented by uniform variables and they are backed by vulkan descriptors.

In this tutorial we will read our texture using a sampler variable. (There are other ways, but they are out of

scope for now.) They have a sampler type, in our case sampler2D. This way of accessing textures

has a useful functionality: you can insert texture coordinates that fall in-between pixels. In this case the

result can be the color of the closest pixel or an average of neighboring pixels, depending on the setup.

Then we need texture coordinates. They can be passed as attribute coordinates, but like I said, for every pixel

in between the triangle corners we need texture coordinates as well. This is where the fragment shader's

in variables come in. You can assign variables to these in the vertex shader for every vertex, and

the GPU will calculate values for them for every pixel. By default the result will be a smooth transition between

vertices. The principle will be the same as the weightes sum approach discussed previously.

An example shader can be seen below using these constructs.

#version 460

layout(binding = 0) uniform sampler2D tex_sampler;

layout(location = 0) in vec2 tex_coord;

layout(location = 0) out vec4 fragment_color;

void main()

{

vec4 tex_color = texture(tex_sampler, tex_coord);

fragment_color = vec4(tex_color.rgb, 1.0);

}

Points of interest in the code are the tex_sampler and tex_coord variables.

The variable tex_sampler has a very similar layout qualifier as the one uniform buffers

had. We'll get more familiar with this later in the chapter. The real difference is the type

sampler2D. An uniform buffer had a struct-like definition of its data structure. Samplers are

opaque: you don't know what they look like, you just use them with built in functions like

texture.

The variable tex_coord is an interpolated variable. Vertex shaders can have out

variables, you'll see them later in the chapter, and they have a corresponding in variable

in the fragment shader. They have a layout(location = 0) qualifier, and the

vertex shader's out and the fragment in variables get paired up using the

value of location. The vertex shader can assign a vaiable to it for every vertex.

After rasterization for every covered pixel the GPU will create a value for the corresponding

in variable in the fragment shader, which by default will be a smooth transition between the

values assigned to the different vertices of the primitive. Here we interpolate the texture coordinate

we want to sample with.

Then we can use these two variables to access a sample of the image. The built-in function call

texture(tex_sampler, tex_coord) expects a sampler variable and a 2D vector, in this case

our interpolated in variable, and samples the image at those texture coordinates. Remember

that our tex_coord is a float vector and its components are between 0.0 and 1.0 here. The code's

semantics are not "reading the [u,v] cell of the texture", because with a float vector you can sample

between pixels, and depending on the configuration it can average pixels of the image and get the

results back. Also since the [u,v] values fall between 0.0 and 1.0 in this case, you can resize the image

and you don't have to adjust the texture coordinates.

Like the uniform buffer, the image is also mapped to a uniform variable using descriptors, and sampler variables can be arrays backed by an array of descriptors.

Now that we went through the GLSL, let's talk about the scope of this chapter!

High level overview

Let's reiterate on how uniform buffers were accessed in shaders, and then we can roughly explain how images will be accessed as well. Then we can lay down a plan for this chapter.

We had to create a uniform buffer, allocate memory for it and assign a range of that memory to the buffer. Shaders did not use uniform buffers directly, but a descriptor within a descriptor set referred to a range of the buffer. During rendering we bound the descriptor set, and in the shader a uniform variable was paired up with the descriptor. When we read data through the uniform variable, the descriptor referred to a range of the uniform buffer, and this is how we found this part of the uniform buffer's memory in the shader.

The way we handle images is analogous to what we just described.

We will need to create an image, allocate memory for it and assign a range of that memory to the image. So far the same. Then the first difference comes: we need an extra indirection, an image view, referring to the image, which the descriptor can refer to. Beyond that we will need another Vulkan object, a sampler, which will hold extra configuration on how to sample the image. Shaders will not use image views or samplers directly, but a descriptor within a descriptor set will refer to an image view and a sampler. During rendering we will bind a descriptor set, and in the shader a uniform variable will be paired up with the descriptor. When we sample the image, the descriptor will refer to the image view and sampler combo, the image view will refer to the image, and this is how data in the image will be found.

Now you can expect some familiar steps when we implement texturing. Now we lay down our plan. We will create more than one image from the start, and the steps will be the following.

- We need to add texture coordinates to our model and adjust the pipeline to read these into attribute variables as well.

- We need to create data and metadata for our images.

- Then we need to create Vulkan images, allocate memory for them, and create an image view for every image.

- Then we will upload our prepared data using the staging buffer and the transfer command buffer we used for vertex and index buffer upload.

- Then we will create a sampler that we can later use for our images.

- Then we extend our descriptor set to refer to our images. We will use a descriptor array to contain a descriptor for every image so all of them can be accessed from shaders based on AMD's Vulkan fast paths presentation.

- We will add a push constant to select the texture to be used in a draw call.

Now that we have an overview of what we are going to do, let's start doing it!

Texture coordinates

We want to assign texture coordinates to every vertex. First we need to define our data, get it uploaded to vertex buffers, and then we need to adjust the pipeline to read the new data into another vertex attribute.

Vertex data setup

In this tutorial we will interleave the texture coordinates with the position coordinates. We have seen a figure in the vertex and index buffer chapter that clearly illustrates the memory layout. The figure is included again below.

Now let's add the texture coordinates to our vertex data!

//

// Vertex and Index data

//

let vertices: Vec<f32> = vec![

// Triangle

// Vertex 0

-1.0, -1.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

1.0, -1.0,

// TexCoord 1

1.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 2

0.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 2

0.5, 1.0,

// Quad

// Vertex 0

-1.0, -1.0,

// TexCoord 0

0.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 1

1.0, -1.0,

// TexCoord 1

1.0, 0.0,

// Vertex 2

1.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 2

1.0, 1.0,

// Vertex 3

-1.0, 1.0,

// TexCoord 3

0.0, 1.0

];

// ...

Now let's adjust the pipeline to read the second vertex attribute as well!

Pipeline setup

Since we read four floats of data per vertex in our binding, we need to adjust the stride, and since we have an additional 2 component vector attribute, we need to add it to the attributes as well.

//

// Pipeline state

//

// ...

let vertex_bindings = [

VkVertexInputBindingDescription {

binding: 0,

stride: 4 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>() as u32,

inputRate: VK_VERTEX_INPUT_RATE_VERTEX,

}

];

let vertex_attributes = [

VkVertexInputAttributeDescription {

location: 0,

binding: 0,

format: VK_FORMAT_R32G32_SFLOAT,

offset: 0,

},

VkVertexInputAttributeDescription {

location: 1,

binding: 0,

format: VK_FORMAT_R32G32_SFLOAT,

offset: 2 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>() as u32,

}

];

// ...

With the size of the per vertex data being 4 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>(), we assign this

to the stride field of our binding.

We add a new attribute as well, this will hold our texture coordinates. It's almost the same as the position,

just it will have a different location, and an offset. The first

2 * core::mem::size_of::<f32>() is occupied by the position coordinates and the texture

coordinates follow contiguously, so the texture coordinates must have this offset in the offset

field.

Now let's create our images!

Images

Preparing data

First let's create a few constants that are specific to the image's pixel format! Also let's create a convenience struct for our image data. The latter will hold the width, height, format, bytes per pixel and pixel data of the image.

//

// Image data

//

let image_format = VK_FORMAT_R8G8B8A8_SRGB;

let bytes_per_pixel = 4 * core::mem::size_of::<u8>();

let image_texel_block_size = 4;

let image_mem_props = VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_DEVICE_LOCAL_BIT as VkMemoryPropertyFlags;

struct ImageData

{

bytes_per_pixel: usize,

width: usize,

height: usize,

data: Vec<u8>

}

impl ImageData

{

fn get_data_size(&self) -> usize

{

self.width * self.height * self.bytes_per_pixel

}

fn get_pixel(&mut self, x: usize, y: usize) -> &mut [u8]

{

let begin = (y * self.width + x) * self.bytes_per_pixel;

let end = (y * self.width + x + 1) * self.bytes_per_pixel;

&mut self.data[begin..end]

}

}

let mut image_data_array = [

ImageData {

bytes_per_pixel: bytes_per_pixel,

width: 4,

height: 4,

data: Vec::new()

},

ImageData {

bytes_per_pixel: bytes_per_pixel,

width: 8,

height: 8,

data: Vec::new()

}

];

// ...

The ImageData is a custom structure and it is self explanatory. We will want two textures, so we

create two instances of this struct. Later we will fill it with data.

What is very important and can be forgotten is the image_texel_block_size. Our

image will have the pixel format VK_FORMAT_R8G8B8A8_SRGB. We will copy data into it using transfer

commands, and the offset of the data in the staging buffer must align to a format specific texel block size. As the

spec

says

Copy regions for the image must be aligned to a multiple of the texel block extent in each dimension, except at the edges of the image, where region extents must match the edge of the image.

This texel block size can be found in the spec for every format.

Now let's fill our ImageData with pixel data. We generate this data in a loop. If you want to

read textures from a file, that is going to be your homework.

//

// Image data

//

// ...

// Pixel data

image_data_array[0].data = vec![0xFF; image_data_array[0].get_data_size()];

for i in 0..image_data_array[0].height

{

for j in 0..image_data_array[0].width

{

let pixel_data = image_data_array[0].get_pixel(i, j);

pixel_data[0] = if i % 2 == 0 { 0xA0 } else { 0xFF };

pixel_data[1] = if j % 2 == 0 { 0xA0 } else { 0xFF };

pixel_data[2] = 0xA0;

pixel_data[3] = 0xFF;

}

}

image_data_array[1].data = vec![0xFF; image_data_array[1].get_data_size()];

for i in 0..image_data_array[1].height

{

for j in 0..image_data_array[1].width

{

let pixel_data = image_data_array[1].get_pixel(i, j);

pixel_data[0] = if i % 2 == 0 { 0xC0 } else { 0xFF };

pixel_data[1] = if j % 2 == 0 { 0xC0 } else { 0xFF };

pixel_data[2] = 0xFF;

pixel_data[3] = 0xFF;

}

}

// ...

Now we have a few constants, image metadata and image data. Now it's time to start creating Vulkan objects.

For every texture we must create a VkImage, a VkDeviceMemory backing it and a

VkImageView. We already touched on some of this in the chapters

swapchain creation and

clearing the screen, but we

will see some new things and elaborate on some previously seen things.

Remember that we will still create a separate device memory for every image and in the real world you should still not do this! This is only for learning!

Image creation

First we create our VkImage. Some things will be familiar and some things will be new.

We briefly talked about tiling when we created our swapchain. Images can be laid out in at least two different ways: linear and optimal. Previously we summarized that optimal is faster and so we use that, but now we will elaborate a bit.

In Vulkan an image's tiling define how the image's data is laid out in memory. We cover two values, linear and optimal.

Linear tiling is a tiling which has a well defined row major order possibly with padding. You can map the image's memory and make assumptions about its memory layout when reading or writing.

Optimal tiling is a tiling where the image's memory layout is implementation dependent and most likely faster than linear. It can vary from GPU to GPU.

Using linear tiling is generally not recommended. Optimal tiling on the other hand has an unknown memory layout, and you cannot just map its memory and write to it. One way of properly initializing it is using transfer commands.

Beyond tiling, images have usages such as VK_IMAGE_USAGE_TRANSFER_DST_BIT as well. The question is

what usage flags are supported when the image is tiled optimally? We already had to check for something like that

during swapchain creation, but now we will do it generically for any image.

We are curious about whether our image can be used as a sampled image in a shader, so we query the format properties and check for it.

//

// Textures

//

let mut format_properties = VkFormatProperties::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetPhysicalDeviceFormatProperties(

chosen_phys_device,

image_format,

&mut format_properties

);

}

if format_properties.optimalTilingFeatures & VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_SAMPLED_IMAGE_BIT as VkFormatFeatureFlags == 0

{

panic!("Image format VK_FORMAT_R8G8B8A8_SRGB with VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL does not support usage flags VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_SAMPLED_IMAGE_BIT.");

}

// ...

The function vkGetPhysicalDeviceFormatProperties returns data into a VkFormatProperties

struct. The optimalTilingFeatures bitfield contains certain features such as whether it can be used

as a color attachment or a sampled image in a shader. We are curious about the latter and the presence of

VK_FORMAT_FEATURE_SAMPLED_IMAGE_BIT confirms if it can be used so we check for it and panic if

it is not set to one.

Then we create images and image views for every image that we want to upload.

//

// Textures

//

// ...

let mut images = Vec::with_capacity(image_data_array.len());

let mut image_memories = Vec::with_capacity(image_data_array.len());

let mut image_views = Vec::with_capacity(image_data_array.len());

for image_data in image_data_array.iter()

{

// ...

}

// ...

We iterate over every image data and create the image using the width, height and format.

//

// Textures

//

// ...

for image_data in image_data_array.iter()

{

//

// Image

//

// Create image

let image_create_info = VkImageCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

imageType: VK_IMAGE_TYPE_2D,

format: image_format,

extent: VkExtent3D {

width: image_data.width as u32,

height: image_data.height as u32,

depth: 1

},

mipLevels: 1,

arrayLayers: 1,

samples: VK_SAMPLE_COUNT_1_BIT,

tiling: VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL,

usage: (VK_IMAGE_USAGE_SAMPLED_BIT |

VK_IMAGE_USAGE_TRANSFER_DST_BIT) as VkImageUsageFlags,

sharingMode: VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE,

queueFamilyIndexCount: 0,

pQueueFamilyIndices: core::ptr::null(),

initialLayout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_UNDEFINED

};

println!("Creating image.");

let mut image = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateImage(

device,

&image_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut image

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create image. Error: {}", result);

}

images.push(image);

// ...

}

// ...

There are a lot of fields in VkImageCreateInfo. Some of it will be analogous to some

fields of the swapchain create info, and some will be new.

In Vulkan there are image types other than simple 2D images. We won't cover them here, but know that they exist.

This is why a field called imageType can exist, and we assign VK_IMAGE_TYPE_2D to it,

because we want a simple 2D image.

The field format determines the pixel format of the image. We talked about this extensively in the

swapchain creation chapter, so I just

summarize here: it determines how many bits we have per pixel and what bits store what kinds of data.

Then come lots of fields which will determine the size of our image.

We have extent, which is a VkExtent3D struct. Unlike the swapchain extent, this one is

a 3D extent, because 3D image types also exist. It has a field width, height and

depth. Since our image is a 2D image, its depth will be 1, and the

width and height will be the width and height of the generated image.

Then there is the field mipLevels, which we set to 1. We will not use mipmapping here,

but Alexander Overvoorde has a mipmapping tutorial

if you are interested. The gist of it is that if your triangles are small, but you use a high resolution texture,

the result will be ugly, because you violate the rules of the

Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem.

Long story made short mipmapping lets you store progressively downscaled versions of your image, and lets the

shader sample lower resolution versions, avoiding ugly artifacts.

Then comes arrayLayers, which we will also set to 1. With the right image type a single

VkImage can hold an array of images, but we will not talk about them here.

It can be a useful feature worth gooling, but the details are out of scope for this chapter.

Then there is samples if you wanted to use multisampling. We do not use multisampling, so we just

set it to VK_SAMPLE_COUNT_1_BIT and do not talk about it here.

Alexander Overvoorde has a

multisampling tutorial as well if you

are interested.

We already talked about tiling. The field tiling will determine whether we lay it out optimally or

some other way. We assign the value VK_IMAGE_TILING_OPTIMAL

Then we have usage, which is analogous to the ones we used for buffers. It enables the usage of our

image for certain purposes, such as being a color attachment, the destination of memory transfer commands or

being sampled from shaders. The value VK_IMAGE_USAGE_SAMPLED_BIT | VK_IMAGE_USAGE_TRANSFER_DST_BIT

enables the latter two usages.

The following three fields, sharingMode, queueFamilyIndexCount and

pQueueFamilyIndices are related to sharing modes. We only want to use our images from a single queue,

and we will perform data upload from our graphics queue, so we can set sharingMode to

VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE. Then queueFamilyIndexCount can be 0, and

pQueueFamilyIndices can be core::ptr::null().

Finally the last parameter will be initialLayout. Beyond the tiling, images can have memory layouts

that make them faster to use for certain purposes. We will cover this as we go, for now since the image does not

contain useful data yet, it will be VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_UNDEFINED.

This was a lot. Finally after setting all of these fields we can create our image.

At the end of the program we destroy our image.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

for image in images

{

println!("Deleting image");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyImage(

device,

image,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

}

// ...

Allocating memory

Now we allocate memory for it. The process will be familiar: we get the supported memory types, allocate suitable memory and bind it to the image.

//

// Textures

//

// ...

for image_data in image_data_array.iter()

{

// ...

// Create memory

let mut mem_requirements = VkMemoryRequirements::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetImageMemoryRequirements(

device,

image,

&mut mem_requirements

);

}

let mut chosen_memory_type = phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount;

for i in 0..phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

if mem_requirements.memoryTypeBits & (1 << i) != 0 &&

(phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypes[i as usize].propertyFlags & image_mem_props) == image_mem_props

{

chosen_memory_type = i;

break;

}

}

if chosen_memory_type == phys_device_mem_properties.memoryTypeCount

{

panic!("Could not find memory type.");

}

let image_alloc_info = VkMemoryAllocateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_MEMORY_ALLOCATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

allocationSize: mem_requirements.size,

memoryTypeIndex: chosen_memory_type

};

println!("Image size: {}", mem_requirements.size);

println!("Image align: {}", mem_requirements.alignment);

println!("Allocating image memory");

let mut image_memory = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkAllocateMemory(

device,

&image_alloc_info,

core::ptr::null(),

&mut image_memory

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Could not allocate memory. Error: {}", result);

}

image_memories.push(image_memory);

// Bind image to memory

let result = unsafe

{

vkBindImageMemory(

device,

image,

image_memory,

0

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to bind memory to image. Error: {}", result);

}

// ...

}

// ...

Selecting a memory type and allocation is analogous to the way we did for a VkBuffer.

This time we get the memory requirements with vkGetImageMemoryRequirements, and

bind with vkBindImageMemory. The parameters are almost the same. Memory type selection

and allocation happens the same way.

I said it a thousand times but I'll say it again: we allocate a separate VkDeviceMemory for every

image. Remember that this is horrible API usage and in a real world application you should not do this.

It will do for a small sample application and for learning.

When the program finishes, we deallocate the memory.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

for image_memory in image_memories

{

println!("Deleting image device memory");

unsafe

{

vkFreeMemory(

device,

image_memory,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

}

// ...

ImageView creation

Images won't be used directly when sampling it from a shader. Instead we will use an image view just as we did in the clearing the screen chapter for framebuffers.

The creation of image views will be familiar.

//

// Textures

//

// ...

for image_data in image_data_array.iter()

{

// ...

//

// Image view

//

let image_view_create_info = VkImageViewCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_VIEW_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

image: image,

viewType: VK_IMAGE_VIEW_TYPE_2D,

format: image_format,

components: VkComponentMapping {

r: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

g: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

b: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY,

a: VK_COMPONENT_SWIZZLE_IDENTITY

},

subresourceRange: VkImageSubresourceRange {

aspectMask: VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_COLOR_BIT as VkImageAspectFlags,

baseMipLevel: 0,

levelCount: 1,

baseArrayLayer: 0,

layerCount: 1

}

};

println!("Creating image view.");

let mut image_view = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateImageView(

device,

&image_view_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut image_view

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create image view. Error: {}", result);

}

image_views.push(image_view);

}

// ...

Image view creation is almost exactly the same here as it was for the framebuffers. The only things that differ

are image, which is set to our texture, not the swapchain image, and format, which

is no longer set to the swapchain format, but the textures' format, image_format.

We will not elaborate on this any further than we did in the clearing the screen chapter.

These image views need to be destroyed when the program finishes.

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

for image_view in image_views

{

println!("Deleting image view");

unsafe

{

vkDestroyImageView(

device,

image_view,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

}

// ...

Data upload

Now we have uninitialized images, and we have image data separately in our image_data_array

along with some metadata. We need to move the data into our images, and this is done with copy commands

and the staging buffer.

Just as we did with the vertex and index buffers, we reserve space in the staging buffer for the image data. Then we copy the image data into the right regions. What's going to be different is the copy command. Previously we copied buffers. Since buffers represent simple linear data, copying was simple. Images are not simple linear data. They may be multidimensional, and they may be laid out in memory nontrivially. For instance maybe it is laid out in 4x4 blocks. Because of this they need separate copy commands that copy from the buffer to the image and arranges the data the right way.

Now that we learned a bit of context let's get our hands dirty! First we adjust our staging buffer so the image data will fit in. We put them right after vertex and index data. The code can be seen below.

//

// Staging buffer size

//

let geometry_data_end = vertex_data_size + index_data_size;

// Padding image offset to image texel block size

let image_align_remainder = geometry_data_end % image_texel_block_size;

let image_padding = if image_align_remainder == 0 {0} else {image_texel_block_size - image_align_remainder};

let image_data_offset = geometry_data_end + image_padding;

let image_data_total_size = image_data_array.iter().fold(0, |sum, image| {sum + image.get_data_size()});

let staging_buffer_size = image_data_offset + image_data_total_size;

// ...

Remember what I said when we defined the image data. We created a constant, image_texel_block_size,

and we cited the spec that the image data in the staging buffer must align to this constant, so we add padding

after the vertex and index data.

Now with the staging_buffer_size being big enough and having image_data_offset point

to a place inside the staging buffer where we can store the image data, let's copy the data into it!

//

// Uploading to Staging buffer

//

// ...

unsafe

{

// ...

//

// Copy image data to staging buffer

//

let mut current_image_data_offset = image_data_offset;

for image_data in image_data_array.iter()

{

let staging_image_data_void = data.offset(current_image_data_offset as isize);

let staging_image_data_typed: *mut u8 = core::mem::transmute(staging_image_data_void);

core::ptr::copy_nonoverlapping::<u8>(

image_data.data.as_ptr(),

staging_image_data_typed,

image_data.data.len()

);

current_image_data_offset += image_data.data.len();

}

vkUnmapMemory(

device,

staging_buffer_memory

);

}

// ...

We iterate over every element of image_data_array, and one after another we copy their data

into the staging buffer and increase the offset for the next image.

Now we can start uploading. Let's go to the transfer command buffer we used in the staging buffer chapter!

//

// Memory transfer

//

{

// ...

let result = unsafe

{

vkBeginCommandBuffer(

transfer_cmd_buffer,

&cmd_buffer_begin_info

)

};

// ...

//

// Copy image data from staging buffer to image

//

// ...

let result = unsafe

{

vkEndCommandBuffer(

transfer_cmd_buffer

)

};

// ...

}

// ...

Before we copy the data from the staging buffer to the image, we must face that images are even weirder than we thought it to be.

We have already seen that tiling has an effect on how the image is laid out in memory, but now we have something extra: layouts.

Beyond tiling the image may be laid out in memory in such a way that different operations are faster on it.

For instance an image in VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OPTIMAL is arranged in a way that using

it as a color attachment is faster. The layout VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_TRANSFER_DST_OPTIMAL may make the

image faster to copy to, and VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_SHADER_READ_ONLY_OPTIMAL may make it faster to read

from in shaders.

We already had a taste of this when we cleared the screen. We configured the render pass to transition our

swapchain images to VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_COLOR_ATTACHMENT_OPTIMAL before render passes, and then

into VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_PRESENT_SRC_KHR for presentation.

However during memory transfer we will not have a render pass. The way image layout transition happens outside of render passes is by using memory barriers, so let's talk about barriers.

In Vulkan a pipeline barrier is an execution/memory dependency between two sets of commands. Pipeline barriers are recorded as a command in a command buffer, and the pipeline barrier defines a dependency between previous and subsequent commands. During recording the pipeline barrier takes a source and destination pipeline stage, and the pipeline stage of the previous commands must complete before the destination pipeline stage.

Pipeline barriers may take a list of memory barriers. A memory barrier defines a set of memory access operations within the source and destination pipeline stages that must wait for each other. The specified memory access operations on the destination pipeline stage will be blocked until the specified memory access operations on the source pipeline stages finish.

Memory barriers may take buffer or image subresources whose memory accesses they need to synchronize, and for images layout transitions are also specified with memory barriers. If you record a layout transition, then after its execution the image will change its layout from the old layout to the new layout.

There is a blog post from Khronos Group about Vulkan synchronization if you want more details. The Vulkan spec also has a synchronization chapter if you need more info.

Now that we talked a lot about image layouts, pipeline barriers, memory barriers and layout transitions,

let's record an image memory barrier that transitions our images to

VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_TRANSFER_DST_OPTIMAL! That way you'll understand things better.

//

// Memory transfer

//

{

// ...

//

// Copy image data from staging buffer to image

//

let mut transfer_dst_barriers = Vec::with_capacity(images.len());

for image in images.iter()

{

transfer_dst_barriers.push(

VkImageMemoryBarrier {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_MEMORY_BARRIER,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

srcAccessMask: VK_ACCESS_HOST_WRITE_BIT as VkAccessFlags,

dstAccessMask: VK_ACCESS_TRANSFER_WRITE_BIT as VkAccessFlags,

oldLayout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_UNDEFINED,

newLayout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_TRANSFER_DST_OPTIMAL,

srcQueueFamilyIndex: VK_QUEUE_FAMILY_IGNORED as u32,

dstQueueFamilyIndex: VK_QUEUE_FAMILY_IGNORED as u32,

image: *image,

subresourceRange: VkImageSubresourceRange {

aspectMask: VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_COLOR_BIT as VkImageAspectFlags,

baseMipLevel: 0,

levelCount: 1,

baseArrayLayer: 0,

layerCount: 1

}

}

);

}

unsafe

{

vkCmdPipelineBarrier(

transfer_cmd_buffer,

VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_HOST_BIT as VkPipelineStageFlags,

VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_TRANSFER_BIT as VkPipelineStageFlags,

0,

0,

core::ptr::null(),

0,

core::ptr::null(),

transfer_dst_barriers.len() as u32,

transfer_dst_barriers.as_ptr()

);

}

// ...

}

// ...

Let's look at the parameters of vkCmdPipelineBarrier! The first one is the command buffer, nothing

special. The second and the third however will be the srcStageMask and dstStageMask.

When we defined a pipeline barrier, we talked about how the source stages must complete before the destination

stages. We define those in these two parameters. The source stage will be VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_HOST_BIT,

and what's important is the destination stage being VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_TRANSFER_BIT. The layout

transition will need to happen before this pipeline stage, because this is where the copy commands from the

staging buffer to the image will be performed. The parameter dependencyFlags is some advanced

parameter that we can just set to zero. The really important things come after.

The remaining parameters are three arrays and their sizes. The memoryBarrierCount and

pMemoryBarriers combo takes an array of global memory barriers. We do not use these right now.

Then there is the bufferMemoryBarrierCount and pBufferMemoryBarriers combo, which

takes an array of buffer memory barriers. We also do not use these. We will only use the third one, the

imageMemoryBarrierCount and pImageMemoryBarriers combo. This takes an array of

image memory barriers, and this is finally what we are looking for.

We will collect our barriers for every image into an array of image memory barriers and submit them all at

once. This is the recommended practice by pretty much every guide I've ever seen. Let's look at how we

construct a single VkImageMemoryBarrier for a single image!

One of the important fields right now is the image field, which identifies the image the

barrier refers to. Then we care about oldLayout and newLayout, after all they're

kinda the point right now. Since our newly created image is uninitialized, it doesn't have meaningful

data inside it, and setting oldLayout to VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_UNDEFINED will pretty

much discard its contents. The newLayout will be VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_TRANSFER_DST_OPTIMAL,

because we want to perform a copy operation, and this layout will be the best for that.

The field subresourceRange is also worth mentioning, it gets filled the same way the image view

create info's subresource info was filled. We have a single mip level and a single array layer, and our image

containt color channels, so we fill the VkImageSubresourceRange accordingly.

Finally let's talk about srcAccessMask and dstAccessMask. The field

dstAccessMask is set to VK_ACCESS_TRANSFER_WRITE_BIT, because we definitely want

any transfer command to only write when the layout transition finishes. The srcAccessMask

is set to VK_ACCESS_HOST_WRITE_BIT because the closest thing that we ever did that is related

to our current procedure is writing the staging buffer from the host.

Now that we constructed the VkImageMemoryBarrier for the image processed by the current iteration,

we add it to an array, and submit the whole array to the vkCmdPipelineBarrier all at once. Whenever

you see a guide saying "batch your barriers", this is what they mean: collect many barriers into an array and

record them all at once.

Now that we recorded our image memory barriers performing the layout transition, let's record the transfer commands!

//

// Memory transfer

//

{

// ...

//

// Copy image data from staging buffer to image

//

// ...

let mut current_image_data_offset = image_data_offset;

for (image_data, image) in image_data_array.iter().zip(images.iter())

{

let copy_region = [

VkBufferImageCopy {

bufferOffset: current_image_data_offset as VkDeviceSize,

bufferRowLength: 0,

bufferImageHeight: 0,

imageSubresource: VkImageSubresourceLayers {

aspectMask: VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_COLOR_BIT as VkImageAspectFlags,

mipLevel: 0,

baseArrayLayer: 0,

layerCount: 1

},

imageOffset: VkOffset3D {

x: 0,

y: 0,

z: 0

},

imageExtent: VkExtent3D {

width: image_data.width as u32,

height: image_data.height as u32,

depth: 1

}

}

];

unsafe

{

vkCmdCopyBufferToImage(

transfer_cmd_buffer,

staging_buffer,

*image,

VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_TRANSFER_DST_OPTIMAL,

copy_region.len() as u32,

copy_region.as_ptr()

);

}

current_image_data_offset += image_data.data.len();

}

// ...

}

// ...

The function performing the copy command is vkCmdCopyBufferToImage. Its parameters are the

command buffer, the source buffer, which is the staging buffer, the destination image, its layout, which

will be VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_TRANSFER_DST_OPTIMAL, after all we just transitioned them into it,

and an array of VkBufferImageCopy structs that define which parts of the staging buffer should

be copied to which parts of the image.

There will be one VkBufferImageCopy instance per image, which will do for our simple case.

For every image we have the whole image data in the staging buffer, which we want to copy to the whole image.

First we talk about the fields defining the data source and the data format.

The field bufferOffset contains the offset in the staging buffer where the image data resides.

The bufferRowLength and bufferImageHeight fields define how the data is laid

out in memory. Our data is tightly packed, every row is directly followed by another row, so we can set these

to 0.

Then we talk about the destination. The field imageSubresource is a

VkImageSubresourceLayers struct. We still don't talk too much about aspectMask,

we just set it VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_COLOR_BIT. We talk about everything else. We have a single

array layer with a single mipmap level. We identify this by setting mipLevel and

baseArrayLayer to 0, which identifies the first array layer and first mip level

as the beginning of the subresource, and set layerCount to 1, identifying our single

array layer.

Then we identify a region within our subresource using an offset and dimensions, as the API allows copying to

only part of the image. We update the whole image, so the offset will be zero and the dimension will be the

dimension of the image. The field imageOffset is a VkOffset3D, all three of its

members will be 0, and imageExtent is a VkExtent3D, its

width and height is set to the image height and the depth is set

to 1, since this is a simple 2D image.

This pretty much covers everything related to copying.

After copying we transition the images to the layout VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_SHADER_READ_ONLY_OPTIMAL

to make sampling from shaders as fast as possible.

//

// Memory transfer

//

{

// ...

//

// Copy image data from staging buffer to image

//

// ...

let mut sampler_src_barriers = Vec::with_capacity(images.len());

for image in images.iter()

{

sampler_src_barriers.push(

VkImageMemoryBarrier {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_IMAGE_MEMORY_BARRIER,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

srcAccessMask: VK_ACCESS_TRANSFER_WRITE_BIT as VkAccessFlags,

dstAccessMask: VK_ACCESS_SHADER_READ_BIT as VkAccessFlags,

oldLayout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_TRANSFER_DST_OPTIMAL,

newLayout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_SHADER_READ_ONLY_OPTIMAL,

srcQueueFamilyIndex: VK_QUEUE_FAMILY_IGNORED as u32,

dstQueueFamilyIndex: VK_QUEUE_FAMILY_IGNORED as u32,

image: *image,

subresourceRange: VkImageSubresourceRange {

aspectMask: VK_IMAGE_ASPECT_COLOR_BIT as VkImageAspectFlags,

baseMipLevel: 0,

levelCount: 1,

baseArrayLayer: 0,

layerCount: 1

}

}

);

}

unsafe

{

vkCmdPipelineBarrier(

transfer_cmd_buffer,

VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_TRANSFER_BIT as VkPipelineStageFlags,

VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_FRAGMENT_SHADER_BIT as VkPipelineStageFlags,

0,

0,

core::ptr::null(),

0,

core::ptr::null(),

sampler_src_barriers.len() as u32,

sampler_src_barriers.as_ptr()

);

}

// ...

}

// ...

This time the barrier will have the pipeline stages VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_TRANSFER_BIT and

VK_PIPELINE_STAGE_FRAGMENT_SHADER_BIT, the srcAccessMask will be set to

VK_ACCESS_TRANSFER_WRITE_BIT and the dstAccessMask will be

VK_ACCESS_SHADER_READ_BIT, because we want to synchronize between the transfer write

and the fragment shader read operations.

Beyond these the only things that are different are the oldLayout, which is

VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_TRANSFER_DST_OPTIMAL, and newLayout, which is

VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_SHADER_READ_ONLY_OPTIMAL. Now we finished the copy commands and want to transition

the image layout from transfer dst optimal to shader read only optimal.

Now the image upload is complete and the image is in the right state to use from shader. It's time to explore a missing puzzle piece, the sampler.

Sampler creation

For texturing we need an additional Vulkan object called a sampler. Without going into too much detail a sampler contains data about...

- How to average neighboring pixels

- How to react when the texture is overindexed (repeating, mirrored repeating, etc.)

- Many other features that we will ignore right now. If you are interested, you can read the spec.

Let's create one!

//

// Sampler

//

let sampler_create_info = VkSamplerCreateInfo {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_SAMPLER_CREATE_INFO,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

flags: 0x0,

magFilter: VK_FILTER_NEAREST,

minFilter: VK_FILTER_NEAREST,

mipmapMode: VK_SAMPLER_MIPMAP_MODE_NEAREST,

addressModeU: VK_SAMPLER_ADDRESS_MODE_CLAMP_TO_EDGE,

addressModeV: VK_SAMPLER_ADDRESS_MODE_CLAMP_TO_EDGE,

addressModeW: VK_SAMPLER_ADDRESS_MODE_CLAMP_TO_EDGE,

mipLodBias: 0.0,

anisotropyEnable: VK_FALSE,

maxAnisotropy: 0.0,

compareEnable: VK_FALSE,

compareOp: VK_COMPARE_OP_NEVER,

minLod: 0.0,

maxLod: 0.0,

borderColor: VK_BORDER_COLOR_INT_OPAQUE_BLACK,

unnormalizedCoordinates: VK_FALSE

};

println!("Creating sampler.");

let mut sampler = core::ptr::null_mut();

let result = unsafe

{

vkCreateSampler(

device,

&sampler_create_info,

core::ptr::null_mut(),

&mut sampler

)

};

if result != VK_SUCCESS

{

panic!("Failed to create sampler. Error: {}", result);

}

// ...

The configuration is held in a VkSamplerCreateInfo struct. The fields magFilter and

minFilter basically determine how to upscale or downscale the image under certain circumstances.

During fragment shader execution if the fragment's area is smaller than the image's texel size, then the image

needs to be upscaled according the magFilter parameter. If the fragment is larger than the image's

texel size, then it needs to be downscaled according to the minFilter parameter. We set both to

VK_FILTER_NEAREST, which will result in a pixelated up and downscaling. Another commonly used

filter is VK_FILTER_LINEAR which would create a smooth transition between the pixels.

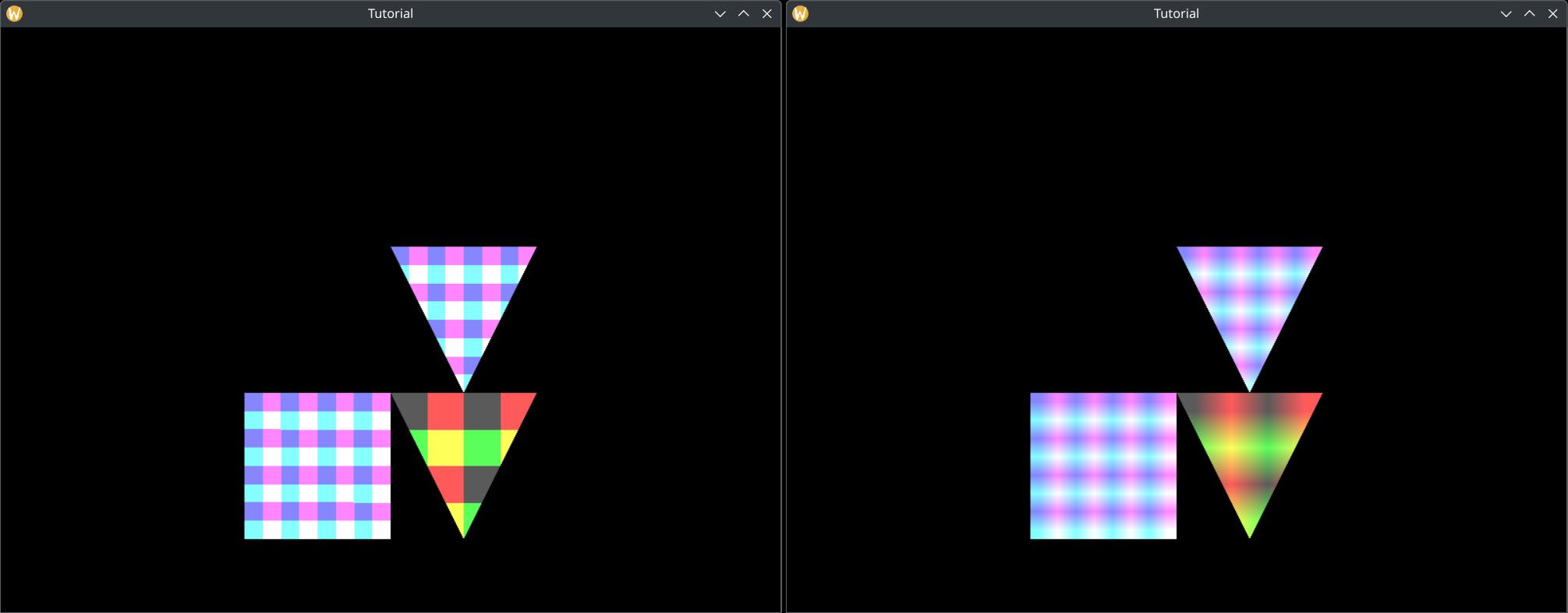

The difference is illustrated below.

VK_FILTER_NEAREST and VK_FILTER_LINEAR

filtering on shapes textured with a low resolution image requiring upscaling. Nearest filtering can be seen on

the left, and linear filtering can be seen on the right. Nearest filtering produces a pixelated image, while

linear filtering produces a smooth transition between pixels resulting in a blurry image.

The field mipmapMode defines how the results of mipmap layers are averaged together, but since we

do not use mipmapping, we just set it to VK_SAMPLER_MIPMAP_MODE_NEAREST and do not talk about it

further.

The fields addressModeU, addressModeV and addressModeW determine what

values to return if we overindex or underindex a sampled image in the shader. It could repeat the image content

with the VK_SAMPLER_ADDRESS_MODE_REPEAT value, it could mirror and repeat the image with

VK_SAMPLER_ADDRESS_MODE_MIRRORED_REPEAT, or it could just clamp it to the edge with

VK_SAMPLER_ADDRESS_MODE_CLAMP_TO_EDGE, repeating the image's edge color. Since we do not

have texture coordinates outside the range of [0,1), we just clamp these values

Another field worth mentioning is unnormalizedCoordinates. If you set this to VK_TRUE,

then the range of texture coordinates would not be [0,1), but [0, width) and [0, height)

(and potentially [0, depth)) respectively. It has restrictions, such as only having one array layer and mip level,

etc. Read the spec if you are interested! It may have its use cases. We do not use it here, and set it to

VK_FALSE

The rest of the parameters are complicated and you can get very fat without them, so we do not talk about them and

just set them to zero, VK_FALSE or something like that.

Once we filled the create info struct, we pass it to vkCreateSampler, which will create the sampler

the standard way.

Let's not forget to destroy our sampler at the end of the program!

//

// Cleanup

//

let result = unsafe

{

vkDeviceWaitIdle(device)

};

// ...

println!("Deleting sampler");

unsafe

{

vkDestroySampler(

device,

sampler,

core::ptr::null_mut()

);

}

// ...

One sampler can be reused by many textures, so we will reuse this single sampler for every texture. If you need to use different filtering or addressing scheme for some textures, you may need a sampler for every configuration, but for textures using the same configuration, you should reuse the corresponding sampler.

Descriptors and descriptor sets

Now that we have images, image views and a sampler, we need to make it accessible to shaders, and we do that the same way we did with uniform buffers: using descriptor sets.

Sampled images are represented by uniform variables in shaders and they are backed by descriptors. Just as with uniform buffers, we need the following steps:

- We need to adjust the descriptor set layout. We add a binding for sampled images.

- We need to adjust the descriptor pool, so it would supply memory for the sampled image descriptors.

- We need to write the descriptors within the descriptor set so they would refer to our images and samplers.

Beyond these sampled images share an additional similarity with uniform buffers: they sampler variable in the shader can be an array, and it can be backed by an array of descriptors. Just as we bound every frame's uniform buffer range during rendering, we can bind every texture all at once.

This is actually an approach recommended by AMD in their Vulkan fast paths presentation. Some not very modern mobile GPUs do not work well with it (or at all), but on desktop this is the modern approach, so this tutorial takes this approach.

We will bind every texture during rendering and bind them all at once during rendering. Just as we did with the frame index, we will use a push constant to index into the sampler array do determine which texture to use for a given draw call.

Now that we laid out the plan, let's get started!

Checking for dynamic indexing support

Like with uniform buffers, not every GPU allows indexing into an array of sampled images with a dynamically uniform index. For instance some not very modern mobile GPUs do not support it. We need to check during physical device selection whether the selected GPU supports it.

This can be determined by checking the shaderSampledImageArrayDynamicIndexing field in

VkPhysicalDeviceFeatures.

//

// Checking physical device capabilities

//

// Getting physical device features

let mut phys_device_features = VkPhysicalDeviceFeatures::default();

unsafe

{

vkGetPhysicalDeviceFeatures(

chosen_phys_device,

&mut phys_device_features

);

}

// ...

if phys_device_features.shaderSampledImageArrayDynamicIndexing != VK_TRUE

{

panic!("shaderSampledImageArrayDynamicIndexing feature is not supported.");

}

// ...

After checking its availability we need to explicitly enable it during device creation by setting

the shaderSampledImageArrayDynamicIndexing to VK_TRUE in the

VkPhysicalDeviceFeatures passed during device creation the same way we did with uniform buffers.

//

// Device creation

//

// ...

let mut phys_device_features = VkPhysicalDeviceFeatures::default();

// Enabling requested features

phys_device_features.shaderUniformBufferArrayDynamicIndexing = VK_TRUE;

phys_device_features.shaderSampledImageArrayDynamicIndexing = VK_TRUE;

// ...

Descriptor set layout

Now we need to adjust the descriptor set layout to have a new binding holding the sampled image descriptors.

//

// Descriptor set layout

//

let max_ubo_descriptor_count = 8;

let max_tex2d_descriptor_count = 2;

let layout_bindings = [

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding {

binding: 0,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

descriptorCount: max_ubo_descriptor_count,

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

pImmutableSamplers: core::ptr::null()

},

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding {

binding: 1,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER,

descriptorCount: max_tex2d_descriptor_count,

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

pImmutableSamplers: core::ptr::null()

}

];

// ...

We just add a new VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding to the layout_bindings array.

The binding will be 1. The descriptorType required for sampled images

is VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER. Since we will make every texture available through

our descriptors, and we have two textures, the descriptorCount will be set to a newly created variable,

max_tex2d_descriptor_count which will be 2, and we will do texturing in the fragment

shader, so stageFlags will be set to VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT.

We just need to add this element to the array, and the creation logic from the previous chapter will work correctly.

Now let's add a new push constant for the texture id.

Texture ID as push constant

Now let's go to the pipeline layout creation logic and let's add a new push constant range that will hold the texture id.

//

// Pipeline layout

//

// ...

// Object ID + Frame ID

let vertex_push_constant_size = 2 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32;

// Texture ID

let fragment_push_constant_size = 1 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32;

let push_constant_ranges = [

VkPushConstantRange {

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

offset: 0,

size: vertex_push_constant_size,

},

VkPushConstantRange {

stageFlags: VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

offset: vertex_push_constant_size,

size: fragment_push_constant_size,

}

];

// ...

Now that we have more than one push constant range, the way they work will be more visible. When you issue

a vkCmdPushConstants command, the offset and size parameters will be

interpreted within a single byte array range. Some of this range may fill variables in the vertex shader,

some may fill variables in the fragment shader.

We modify our pre existing push constant range a little bit. We rename the variable holding its size to

vertex_push_constant_size to identify that it is the size of the vertex shader's push constant

range.

Then we add a new VkPushConstantRange for the range filling the fragment shader push constants.

The range will come after the vertex shader's push constant range, so the offset

will be vertex_push_constant_size, and it must hold a single 32 bit integer, so we create a

variable, fragment_push_constant_size, to hold the value

1 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>(), and we assign this variable to the size.

We don't have to modify anything else, the existing pipeline layout creation logic from the previous chapter will work fine.

Pay attention: you may want to revisit this section after completing the tutorial, and you may need to digest it a bit.

Descriptor set

Now we need to resize our descriptor pool so it will have enough space to allocate our combined image sampler descriptor.

We do this by adding a new element to pool_sizes.

//

// Descriptor pool & descriptor set

//

let pool_sizes = [

VkDescriptorPoolSize {

type_: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

descriptorCount: max_ubo_descriptor_count

},

VkDescriptorPoolSize {

type_: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER,

descriptorCount: max_tex2d_descriptor_count

}

];

// ...

The new VkDescriptorPoolSize element in the array will have the type

VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER which is the same we set during descriptor set layout

creation, and the size will be max_tex2d_descriptor_count, the same variable we created when we

modified the descriptor set layout. Now it has enough space to allocate a descriptor set of this layout.

Nothing else needs to be modified around the descriptor pool and descriptor set allocation. The combined image sampler descriptors will be allocated because of the descriptor set layout.

Now we need to fill the combined image sampler descriptors with our textures and our single sampler.

//

// Descriptor pool & descriptor set

//

// ...

// Writing descriptor set

// ...

let mut tex2d_descriptor_writes = Vec::with_capacity(max_tex2d_descriptor_count as usize);

for i in 0..max_tex2d_descriptor_count

{

let image_index = (max_tex2d_descriptor_count as usize - 1)

.min(image_views.len() - 1)

.min(i as usize);

tex2d_descriptor_writes.push(

VkDescriptorImageInfo {

sampler: sampler,

imageView: image_views[image_index],

imageLayout: VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_SHADER_READ_ONLY_OPTIMAL

}

);

}

// ...

Just like the uniform buffer descriptors, these will be written as well, just with a different write info

struct, VkDescriptorImageInfo. It has three fields: sampler, which will refer to

our sampler we created earlier, imageView, which will refer to the image view of our image,

and the imageLayout, which contains the image layout the image is expected to be in. After

data upload we transitioned our images to the layout VK_IMAGE_LAYOUT_SHADER_READ_ONLY_OPTIMAL,

so this is what we will set here.

We create max_tex2d_descriptor_count amount of descriptor writes, which is right now the same

as the amount of textures, but if you increase this number, because your application gets advanced, and so

on, and max_tex2d_descriptor_count will be greater than the amount of textures, then we just

fill the remaining descriptors with the last texture. This is necessary, because by default Vulkan expects

every descriptor that you bind to be properly initialized.

Now that we have the descriptor infos in an array, we add this array to the descriptor write array.

//

// Descriptor pool & descriptor set

//

// ...

let descriptor_set_writes = [

VkWriteDescriptorSet {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_WRITE_DESCRIPTOR_SET,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

dstSet: descriptor_set,

dstBinding: 0,

dstArrayElement: 0,

descriptorCount: ubo_descriptor_writes.len() as u32,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER,

pImageInfo: core::ptr::null(),

pBufferInfo: ubo_descriptor_writes.as_ptr(),

pTexelBufferView: core::ptr::null()

},

VkWriteDescriptorSet {

sType: VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_WRITE_DESCRIPTOR_SET,

pNext: core::ptr::null(),

dstSet: descriptor_set,

dstBinding: 1,

dstArrayElement: 0,

descriptorCount: tex2d_descriptor_writes.len() as u32,

descriptorType: VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER,

pImageInfo: tex2d_descriptor_writes.as_ptr(),

pBufferInfo: core::ptr::null(),

pTexelBufferView: core::ptr::null()

}

];

// ...

We add a new VkWriteDescriptorSet element to the descriptor_set_writes array.

The dstSet will refer to descriptor_set, the dstBinding will be

1, and since we write the whole descriptor array, the dstArrayElement will be

0 and the descriptorCount will be tex2d_descriptor_writes.len(),

which will cover the whole descriptor array.

What differs from the uniform buffer descriptor writes, is that the descriptorType will be

VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER and the corresponding pointer pointing to the

descriptor infos is pImageInfo, which is set to tex2d_descriptor_writes.as_ptr().

Command recording

Now it's time to adjust our rendering commands.

Since we modified the pipeline to read the texture coordinates from the same binding, and modified the vertex data to include texture coordinates, we don't need to do anything else to access the texture coordinates. Also since we added the textures to the same descriptor set that contained the uniform buffer descriptors, and we already bind that descriptor, we don't need anything extra to have our textures bound.

Setting push constant during rendering

We still need to select the right texture, and we will rewrite our shader to select the texture based on a push constant.

We assign texture 0 to our player character

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

// ...

// Setting per frame descriptor array index

// ...

// Setting texture descriptor array index

let texture_index: u32 = 0;

vkCmdPushConstants(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

pipeline_layout,

VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

2 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

&texture_index as *const u32 as *const core::ffi::c_void

);

// Per obj array index

let obj_index: u32 = 0;

// vkCmdPushConstants...

// Draw triangle without index buffer

// This does not even require you to bind an index buffer.

vkCmdDraw(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

3,

1,

0,

0

);

// ...

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

Let's look at the parameters of the newly added vkCmdPushConstants call. First, notice how

when we define texture_index we are very explicit about it needing to be a 32 bit integer.

The last parameter of vkCmdPushConstants is a void pointer, we pass a pointer to

texture_index as this parameter, and it is a minefield if type inference gets the types wrong.

We want to copy a 32 bit integer, so we need to ensure that texture_index does not accidentally

become for instance a 64 bit integer.

The other thing to pay attention to is the offset parameter. We specified that the fragment shader's

push constant range will be after the vertex shader's push constant range, which takes up two

32 bit integers. This is why offset has 2 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>() assigned

to it.

Beyond that the rest is trivial. We push 32 bits, so the size is

core::mem::size_of::<u32>(), and it needs to be available from the fragment shader, so the

stageFlags will be VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT.

This is the part that may help you digest the part when we specified the extra push constant range.

Now we are finished with setting the texture of our player character. Let's assign texture 1 to non player characters!

//

// Rendering commands

//

// ...

unsafe

{

vkCmdBeginRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

&render_pass_begin_info,

VK_SUBPASS_CONTENTS_INLINE

);

// ...

// ...

// Setting texture descriptor array index

let texture_index: u32 = 1;

vkCmdPushConstants(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

pipeline_layout,

VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT as VkShaderStageFlags,

2 * core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

core::mem::size_of::<u32>() as u32,

&texture_index as *const u32 as *const core::ffi::c_void

);

// Per obj array index

let obj_index: u32 = 1;

// vkCmdPushConstants...

// Draw triangle with index buffer

vkCmdDrawIndexed(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

3,

1,

0,

0,

0

);

// Per obj array index

let obj_index: u32 = 2;

// vkCmdPushConstants...

// Draw quad with index buffer

vkCmdDrawIndexed(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index],

6,

1,

3,

3,

0

);

vkCmdEndRenderPass(

cmd_buffers[current_frame_index]

);

}

The code is roughly the same, just the value of texture_index is different.

Finally we have both the texture descriptor array bound and the push constant set, but we do not yet use them from our shaders, so let's change that!

Shaders

Vertex shader

First we need to modify the vertex shader to read the texture coordinates passed in the second attribute and pass it to a later pipeline stage that will interpolate it and forward the interpolated value to the fragment shader.

#version 460

struct CameraData

{

vec2 position;

float aspect_ratio;

};

struct ObjectData

{

vec2 position;

float scale;

};

const uint MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 8;

const uint MAX_OBJECT_COUNT = 3;

layout(std140, set=0, binding = 0) uniform UniformData {

CameraData cam_data;

ObjectData obj_data[MAX_OBJECT_COUNT];

} uniform_data[MAX_UBO_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

layout(push_constant) uniform ResourceIndices {

uint obj_index;

uint ubo_desc_index;

} resource_indices;

layout(location = 0) in vec2 position;

layout(location = 1) in vec2 tex_coord;

layout(location = 0) out vec2 frag_tex_coord;

void main()

{

uint ubo_desc_index = resource_indices.ubo_desc_index;

uint obj_index = resource_indices.obj_index;

vec2 obj_position = uniform_data[ubo_desc_index].obj_data[obj_index].position;

float obj_scale = uniform_data[ubo_desc_index].obj_data[obj_index].scale;

vec2 world_position = obj_position + position * obj_scale;

vec2 cam_position = uniform_data[ubo_desc_index].cam_data.position;

float cam_aspect_ratio = uniform_data[ubo_desc_index].cam_data.aspect_ratio;

vec2 view_position = (world_position - cam_position) * vec2(1.0/cam_aspect_ratio, 1.0);

frag_tex_coord = tex_coord;

gl_Position = vec4(view_position, 0.0, 1.0);

}

First we added layout(location = 1) in vec2 tex_coord. The layout(location = 1) and the

vec2 part correspond to our modifications to the pipeline. There we configured it so the attribute

at location 1 would be a 2D float vector read from the zeroth vertex buffer binding with a

2 * core::mem::size_of:: offset.

We also create another variable layout(location = 0) out vec2 frag_tex_coord. The

layout(location = 0) part gives it an identifier to pair it up with a corresponding fragment shader

variable. The per vertex data written to this variable will be interpolated for every pixel covered by this

triangle.

Then there is a line in the main function, frag_tex_coord = tex_coord, which assigns

the tex_coord attribute to the frag_tex_coord out variable so it will be interpolated

and passed to the fragment shader.

I saved this file as 04_tex_coords.vert into the shader_src/vertex_shaders directory

within the sample directory.

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/04_tex_coords.vert.spv ./shader_src/vertex_shaders/04_tex_coords.vert

Once our binary is ready, we need to load it into the application.

//

// Shader modules

//

// Vertex shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/04_tex_coords.vert.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

// ...

Now let's move on to the fragment shader!

Fragment shader

The fragment shader needs to access the sampled image array containing our textures, read the texture identified by the push constant written during command buffer recording, and access the right texel(s) based on the texture coordinates passed by the vertex shader.

#version 460

const uint MAX_TEX_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT = 2;

layout(set = 0, binding = 1) uniform sampler2D tex_sampler[MAX_TEX_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT];

layout(push_constant) uniform ResourceIndices {

layout(offset = 8) uint texture_id;

} resource_indices;

layout(location = 0) in vec2 frag_tex_coord;

layout(location = 0) out vec4 fragment_color;

void main()

{

uint texture_id = resource_indices.texture_id;

vec4 tex_color = texture(tex_sampler[texture_id], frag_tex_coord);

fragment_color = vec4(tex_color.rgb, 1.0);

}

First we create our tex_sampler variable. The layout(set = 0, binding = 1) says this

uniform variable is described by the descriptors in the binding 1 of the descriptor set

0. Then its type will be sampler2D to indicate that it is a sampled image, and as

you can see, tex_sampler[MAX_TEX_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT] array syntax indicates that it represents

a descriptor array. The array size, MAX_TEX_DESCRIPTOR_COUNT is set to two. Pay attention that

this array size must be the same as the descriptor count set in the descriptor layout.

Then we create our push constant variable resource_indices with a member texture_id.

The layout(push_constant) layout qualifier on resource_indices indicates that its

value comes from a push constant. The layout(offset = 8) layout qualifier on

texture_id corresponds to the push constant range offset set both during pipeline layout creation

(the offset value of the corresponding push_constant_ranges element) and setting the

push constant during command recording (the value 2 * core::mem::size_of::

of the offset parameter of vkCmdPushConstants). This is a byte offset, twice the size

of a 32 bit integer, which is 8 bytes.

The last variable we create is the in variable frag_tex_coord. The layout(location = 0)

part sets its layout location to 0, pairing it up with its vertex shader counterpart. This value will

be interpolated between the values of every tex coord of the triangle vertices.

Finally we put it all together on the line

vec4 tex_color = texture(tex_sampler[texture_id], frag_tex_coord). Let's take it apart!

The function texture expects a sampler and a texture coordinate. The texture coordinate is evident,

the frag_tex_coord in variable. The sampler parameter will be tex_sampler[texture_id],

which is the tex_sampler array's texture_idth array element. The texture_id

comes from the push constant variable resource_indices.texture_id. So again: we select our texture

based on the index inside a push constant, and sample it at the coordinates determined by the interpolated

texture coordinates.

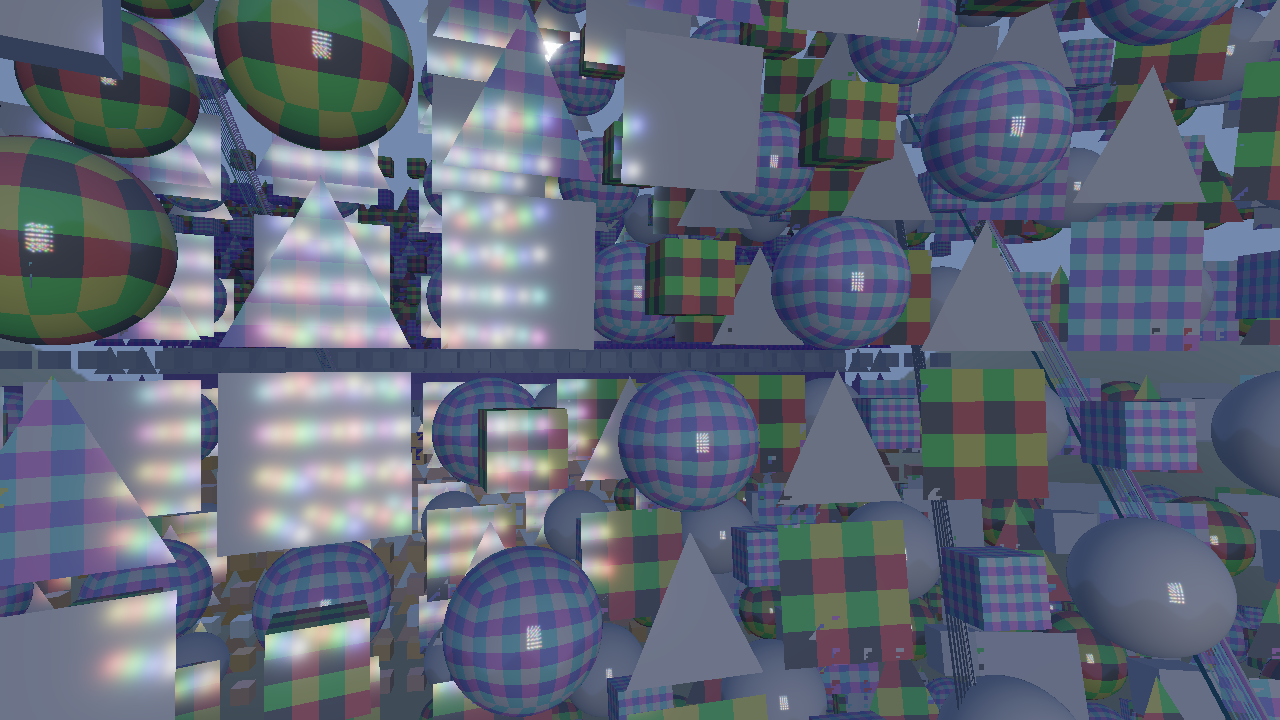

Pay attention that the variable tex_sampler must be indexed with a dynamically uniform variable.

If you do not index it with a dynamically uniform variable, on some architectures (like AMD) it can result in

the shader reading from the wrong texture. A resulting bug can be seen on the figure below. For instance a push

constant set for the draw call will be dynamically uniform, but an interpolated in variable like

frag_tex_coord will likely not be.

We then assign this read color to the fragment_color out variable, writing it to the corresponding

color attachment.

Let's remember the bugs I mentioned in the previous chapter, the one from stackoverflow and the one from stackexchange! Now we know what kind of code produces these.

Our texture_id comes from a push constant and is dynamically uniform.

I saved this file as 01_texture.frag into the shader_src/fragment_shaders directory.

./build_tools/bin/glslangValidator -V -o ./shaders/01_texture.frag.spv ./shader_src/fragment_shaders/01_texture.frag

Once our binary is ready, we need to load this one into the application as well.

//

// Shader modules

//

// ...

// Fragment shader

let mut file = std::fs::File::open(

"./shaders/01_texture.frag.spv"

).expect("Could not open shader source");

// ...

...and that's it!

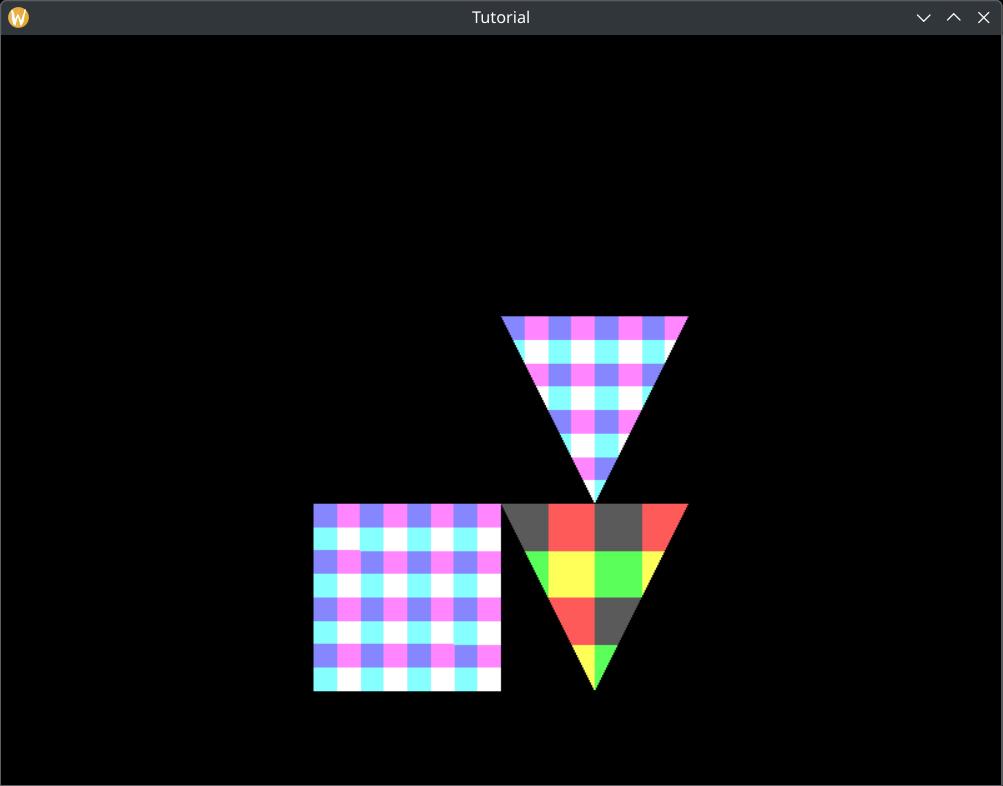

Now our application can render textured models!

Bonus: Descriptor set update for texture upload

Our application is simple: let's upload everything, and then start the main loop. Most real life applications aren't like that. You may want to load textures during gameplay, or a loading screen that may use textures as well, etc. Then you need to update the texture descriptors so the newly loaded textures are accessible. Problem is, without descriptor indexing features enabled a bound descriptor set cannot be updated. Even with descriptor indexing features a descriptor in use must not be updated, so writing an already bound descriptor set is dangerous. You can solve it with some bookkeeping of course.

AMD's Vulkan fast paths presentation recommends descriptor set double buffering as a solution. You create two descriptor sets: descriptor set 0 and descriptor set 1. Descriptor set 0 contains the already loaded textures, and you bind that during rendering. When you load new textures, you have new available textures. You write every available texture into descriptor set 1, and swap them: from now on you bind descriptor set 1 during rendering. When descriptor set 0 is no longer used (this needs to be properly synchronized), you can write to it the next time textures get loaded.

Wrapping up

The journey was long, but finally we have textured shapes on the screen.

We created images and image views, uploaded data to our images, learned layouts and layout transitions and created a sampler.

We also followed AMD's fast path presentation and created a descriptor array to bind them all during rendering and select the right texture using a push constant.

We also added texture coordinates, interpolated them and forwarded them to the fragment shader, sampled the image using the interpolated texture coordinates and used its color to color our shapes.

Next, we will get started with 3D graphics.

The sample code for this tutorial can be found here.

The tutorial continues here.